If your attention during the Women’s World Cup was on the pitch rather than the players, you might have noticed that the matches were all played on real grass. That was a hard-won change, made after the US team complained to FIFA that they sustained more injuries on artificial turf.

In private gardens the opposite trend is happening: British gardens are being dug up and replaced with plastic grass.

However, this is not the flaky, fading stuff on which oranges were once displayed at the grocery store. Today’s artificial grass is nearly identical to the real thing.

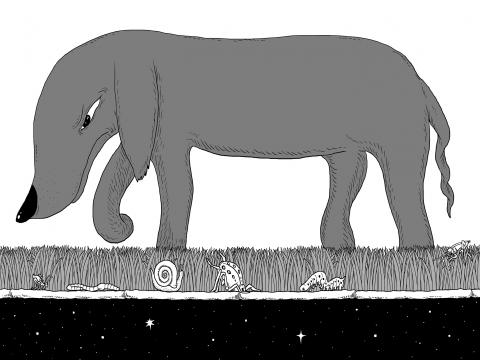

Illustration: Mountain People

With products named after beautiful places — Lake District, Valencia — modern artificial turf mimics not just the mottled coloring and shape of grass blades, but the warm springiness of earth.

Unlike the grass itself, the market is growing. Dozens of specialist firms market fake grass as a replacement for garden lawns.

UK sales surged during last year’s record summer temperatures, according to the industry journal Hortweek, while a report by Up Market Research valued the global market at US$2.5 billion in 2016 and forecasts a “staggering” rise to US$5.8 billion by 2023.

As artificial grass has become much cheaper and more realistic, it now appeals to a wide range of people: city residents with shaded gardens where grass does not grow well, or to carpet urban rooftops and balconies; families with children or dogs who do not want a muddy mess; older or disabled people who struggle to maintain a garden; and schools and nurseries where playgrounds get heavy use, said Andy Driver, sales and marketing director for the artificial turf supplier Evergreens UK.

For many people there is social pressure to “keep up with the Joneses” by having a perfectly trimmed, green lawn the entire year, he said.

Perhaps aware of another kind of social pressure, some firms pitch their products as eco-friendly alternatives.

For example, Royal Grass said that its environmentally friendly turf, called Eco-Sense, is recyclable (“in other words, cradle-to-cradle”) and that it “has the look and feel of natural grass, but outperforms its natural source of inspiration.”

“’Green’ is a premium goal in our quest on how we can make our artificial grass more sustainable. This starts at the beginning of the process, with the careful selection of the raw materials that are used to produce the grass blades,” it said.

However, while the fake grass might indeed be greener, at least in color, its environmental effects are difficult to gloss over.

Paul Hetherington, fundraising director for the charity Buglife, said that artificial turf is far from an eco-friendly alternative to natural grass.

“It blocks access to the soil beneath for burrowing insects, such as solitary bees, and the ground above for soil dwellers such as worms, which will be starved of food beneath it,” he said. “It provides food for absolutely no living creatures.”

This is a particular concern in view of the dramatic global decline in insect species. The UK is on course to miss its own targets for protecting its natural spaces and has lost 97 percent of its wildflower meadows in a single generation.

It is not just wildlife that artificial turf affects. The British Committee on Climate Change recommends rewilding a huge area of UK land and growing many more trees to help tackle global heating by storing carbon.

Not only does fake grass have no climate benefits, but producing the plastic emits carbon and uses fossil fuels.

The common practice of replacing soil with sand to provide a more stable bed for the fake grass also releases even more carbon dioxide stored in the earth, said David Elliott, chief executive of tree-planting charity Trees for Cities.

There is also the matter of microplastics: the tiny particles of plastic that have made their way throughout the globe and are present in food, water and even the air.

Evergreen UK’s turf is made mainly of polyethylene, with polypropylene and polyamide for some purposes.

Driver said that the microplastics problem does not affect the artificial grass industry, because it does not sell single-use products.

“Our products don’t degrade, we’ve always not had it as an issue, basically,” he said, adding that products from legitimate firms conform to standards set by the industry.

Madeleine Berg, project manager at the environmental charity Fidra, said that most plastics are likely to contribute to microplastics through physical and chemical degradation, such as being stepped on and exposed to constant sunlight.

“You would be hard-pressed to say that you have created a product which doesn’t shed anything,” Berg said.

There are also growing concerns about the effects of the synthetic chemicals that are added to artificial grass on human health and the environment.

The EU has been investigating specialist artificial turf used on sports fields for suspected carcinogens, and is considering banning intentionally added microplastics.

While these are different products to those sold to home gardeners, Berg said that artificial pitches are sometimes reused for landscaping.

What happens to fake grass when it reaches the end of its life in 10 to 20 years?

Unlike Royal Grass, Evergreens UK does not market itself as eco-friendly, a term Driver calls “a little bit misleading,” but he was keen to say that his company’s products can be recycled.

However, this can only be done at specialist plants in Europe and it is doubtful that many customers would go the extra mile.

British Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) chief horticulturist Guy Barter said that there is a place for artificial turf as an alternative to paving slabs, gravel and particularly concrete, which is its own environmental nightmare.

“Hard landscaping can be very expensive and people fancy a bit of green in a small garden. We’ve even laid a bit [of artificial grass] ourselves,” Barter said.

“But I don’t think that for all but specialized purposes that it really compares with [real] grass. Not only does it not provide any of the environmental benefits of grass — like soaking up moisture, home for insects, feeding birds, self-sustaining — its life isn’t that long. It gets trampled on and quite soon looks poor. It can’t be relaid or reseeded; it has to be rolled up, lifted and sent to landfill,” he added.

Barter conceded that the root of the problem is social pressure for a perfect green lawn.

“In the mindset of the British public you haven’t really got a garden unless you’ve got a lawn,” he said. “And I think a lot of people are put off by lawns, because there’s so much quite confusing technical speak around it like mowing, feeding, weeding, moss control and overseeding. A lot of people just aren’t interested — they don’t have time in their busy lives.”

There are some environmental benefits to using artificial grass. Unlike a real lawn, fake grass doesn’t need to be mowed — which some people do with electric or fossil fuel mowers — or watered, which is a serious consideration as the UK anticipates increasing water stress due to the climate crisis.

Nor does it require fertilizers or herbicides, some of which have been subject to huge controversy, to achieve a uniform look.

However, lawns can also be maintained without those negative practices and products, and the soil loss problem is real: the RHS’ Greening Grey Britain survey has found a threefold rise in the number of front gardens that have been paved over.

Barter also challenges the idea that artificial turf is maintenance-free, saying that it still needs to be cleaned of litter and moss growth, and some owners have simply replaced mowing with vacuuming.

“There are better solutions that would give people more pleasure than just looking out at this sheet of slowly degrading plastic,” he said.

He suggested planting shady front gardens with tolerant shrubs, such as evergreen bushes, which provide greenery all year round, need little maintenance, suppress weeds, offer food for wildlife and places for birds to nest, and give hedgehogs and frogs cover to travel safely in urban streets.

“After all, we are supposed to be a nation of gardeners,” Barter said.

To Trevor Dines, botanical specialist for charity Plantlife, the popularity of artificial grass shows how disconnected people have become from the natural world.

“Whenever I see artificial grass, my heart sinks — more nature smothered by more plastic. Where once we were famed for our lawns, we now opt for artificial, low-maintenance solutions,” he said. “This is not just to the detriment of wildlife, but to us, too; children can’t make a daisy chain on a plastic lawn.”

In the first year of his second term, US President Donald Trump continued to shake the foundations of the liberal international order to realize his “America first” policy. However, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty and unpredictability, the Trump administration brought some clarity to its policy toward Taiwan. As expected, bilateral trade emerged as a major priority for the new Trump administration. To secure a favorable trade deal with Taiwan, it adopted a two-pronged strategy: First, Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing” chip business from the US, indicating that if Taipei did not address Washington’s concerns in this strategic sector, it could revisit its Taiwan

The stocks of rare earth companies soared on Monday following news that the Trump administration had taken a 10 percent stake in Oklahoma mining and magnet company USA Rare Earth Inc. Such is the visible benefit enjoyed by the growing number of firms that count Uncle Sam as a shareholder. Yet recent events surrounding perhaps what is the most well-known state-picked champion, Intel Corp, exposed a major unseen cost of the federal government’s unprecedented intervention in private business: the distortion of capital markets that have underpinned US growth and innovation since its founding. Prior to Intel’s Jan. 22 call with analysts

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

International debate on Taiwan is obsessed with “invasion countdowns,” framing the cross-strait crisis as a matter of military timetables and political opportunity. However, the seismic political tremors surrounding Central Military Commission (CMC) vice chairman Zhang Youxia (張又俠) suggested that Washington and Taipei are watching the wrong clock. Beijing is constrained not by a lack of capability, but by an acute fear of regime-threatening military failure. The reported sidelining of Zhang — a combat veteran in a largely unbloodied force and long-time loyalist of Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) — followed a year of purges within the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA)