When Florence broke out in lesions on her face, she was convinced it was because she had crossed a black magic curse cast on her as she left Nigeria to work in Russia’s sex trade.

Florence is one of a rising number of women lured in the past few years from impoverished lives in southern Nigeria to Europe with the promise of lucrative work, many ending up selling sex.

Although some of the women knowingly entered into contracts for sex work, few realized they would be trapped like slaves for years, with their traffickers colluding with madams to ensure black magic curses, or juju, stopped them escaping.

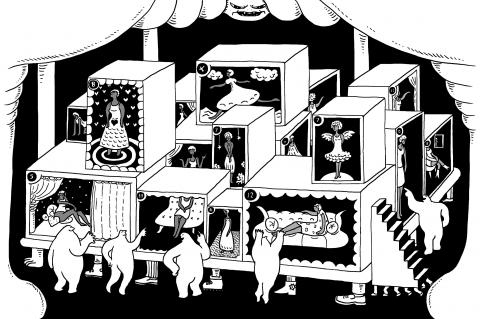

Illustration: Mountain People

For belief in juju to kill or maim is deeply rooted in Edo State, the home of about nine in every 10 Nigerian women trafficked to Europe, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, with a battle now waging to end witchcraft’s hold over trafficking victims.

Florence, 24, said she had not known she was headed for sex work six years ago, when she agreed to a loan to fund a trip to work in Russia in a deal brokered by a pastor from her church.

Before leaving her home in Benin, the capital of Edo, she was taken to a juju priest who used her hair and clothing to make a spell to bind her to her traffickers. She was then taken to Lagos, where she was raped before being sent to Russia.

“They took my pants. They took my bra. They took my pubic hair from my armpits and also from my private parts,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. The madam “used those items she took from me to take as vengeance against me.”

She was convinced that juju was to blame for facial lesions that erupted in 2016 after she refused to give her captors any more money after paying them 45,000 euros (US$52,591) and fled back to Nigeria.

SPELLS AND CURSES

Florence’s fear of black magic if she disobeyed her traffickers, went to the police or failed to pay her debt is typical for many women trafficked from Nigeria, experts have said.

Many end up enslaved after signing a contract to finance their move, leaving them with debts that spiral into thousands of US dollars and take years to pay off.

From 2014 to 2016, there was an almost 10-fold increase in the number of Nigerian women arriving in Italy by boat — about 11,000 — with at least four in five becoming prostitutes, according to the International Organization for Migration.

However, law enforcement officials and campaigners are hoping the intervention this year by Oba Ewuare II, leader of the historic kingdom of Benin, could end the burgeoning trade.

In March, the oba summoned the kingdom’s juju priests to a ceremony at his palace and dismissed the curses they had placed on trafficking victims — and cast a fresh curse on anyone who went against his order.

Since then, anecdotal evidence from people involved in the trade suggests that the trafficking has slowed, although it is too soon for firm data to be collated.

Patience, 42, who has supplemented her income as a hairdresser by selling girls into overseas sex work for about 16 years, said the leader’s ceremony had stopped the trafficking.

“I didn’t hear directly from his mouth, but through the radio and television. The oba has stopped everything,” Patience told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in her home in Benin, where she lives with her husband and four children. “Whenever I go out, I meet girls who beg me to take them to Europe, but I refuse, because I don’t want to die. Everybody is afraid.”

David Edebiri, the second-highest ranking chief in Benin, said he believes that the oba’s involvement, inspired by repeated bad press in the international media, has reduced trafficking and could help bring more traffickers to justice, as many women involved were previously too afraid of juju rituals to testify.

“It has been very, very effective and that if even anything is going on now, it must be a very minute dimension. Not as it was before [when] it was becoming everybody’s game,” he said.

ESCAPING POVERTY

However, with unemployment in Edo at 20 percent, according to the Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics, women especially are hard pressed to find work. Living standards are low, with large families to feed and few outlets to earn.

Nigeria has the most extreme poor people in the world, according to the World Poverty Clock, with almost half of its 180 million population living on less than US$2 a day.

So many women, like Betty, have said the crackdown on traffickers taking girls for sex work in other countries — often with the knowledge of their families — is unlikely to stop the industry.

When Betty touched down in Nigeria from Belgium two years ago, she knelt on the tarmac, raised her hands and thanked God she was home after five years of being trapped in sex work repaying debts.

Now, Betty, 29 and single, cannot wait to get back to Europe.

She has not found work since returning to Benin. She avoids her mother, a fish seller, who is distraught about her daughter’s fall from grace.

“When I was in Europe, I was like a celebrity... I did a lot of things for my family,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation, recalling life before she was deported from Belgium.

“I was their hope, their joy. I was giving my parents feeding money. My elder brother’s children, the four of them, I was also paying their school fees,” Betty said from the one-bedroom home she shares with her brother’s seven-strong family.

She said it was now difficult to stay in Nigeria.

“If I have my way, I will definitely go back,” said Betty, who paid about 50,000 euros to a Nigerian madam in Europe over five years to work in the sex business.

Betty, who did not want to reveal her surname, said she earned thousands of euros in Europe, selling her body several times a day from street corners and a rented flat.

DANGEROUS WORK

It came with its risks.

She injured her back after jumping out of a speeding car to escape one punter. Her flatmate disappeared after going to meet a client.

Florence also spoke of the dangers involved, recalling arriving to meet a client and finding 15 men waiting, and always checking out which doors and windows could be escape routes.

However, some women and their families remain willing to take the risks for the money that can support whole families in Nigeria.

Victor Irorere has two daughters, aged 18 and 21, who have both lived in Europe for at least four years, and he knows they work “with their bodies,” but he relies on their earnings.

“They help me... They often send money,” said Irorere, 47, a bricklayer and father of 11, as he waited outside a juju priest’s shrine in Benin, a live chicken struggling in his hand, to pay for a good luck spell for his daughters.

Kokunre Eghafona, a professor of sociology at the University of Benin who researches human trafficking, said the oba’s curse was not stopping, but just changing patterns in the sex-trafficking trade.

With traffickers and juju priests terrified of the misfortunes that might befall them as a result of the oba’s curse, girls and young women are instead raising their own funds to finance their journeys to Europe and beyond.

The UN this year recorded a sharp fall in the number of migrants reaching Europe by sea, with the biggest change in the once-busy channel between North Africa and Italy.

However, experts said this was because traffickers have found a new market.

Middle Eastern countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Oman, are now the new destinations of choice for Nigerians selling sex, said Nduka Nwanwenne, Benin zonal commander of Nigeria’s anti-trafficking agency.

He said many of the girls are tricked into believing that they will be going to work as house maids and nurses, only to be forced into sex work, while others are going willingly.

“But you know when it comes to willingness, a victim is still a victim. There are some that don’t know the extent of what they are going to do there. They don’t know the extent of exploitation,” Nwanwenne said.

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should