Plastic has been found in ocean-floor sediments 2km below the surface in one of Australia’s most precious and isolated marine environments.

Scientists at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia’s national science agency, discovered the microplastic pieces while analyzing samples taken hundreds of kilometers offshore at the bottom of the Great Australian Bight — a so-called “pristine” biodiversity hotspot and marine treasure.

Conservationists and scientists said the discovery off the South Australian coast should act as a “wake-up call” for governments and corporations to cut unnecessary use of plastics and to “legislate and incentivize” to tackle the growing ocean plastics problem.

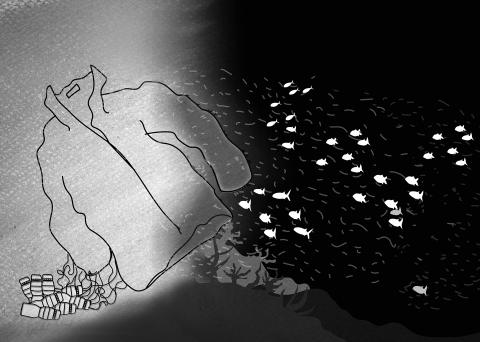

Illustration: June Hsu

“This points to just how ubiquitous plastics are in our environment. Even in deep-sea sediments around Australia, which is a developed country, we still find plastic — anthropogenic waste — from the bottom of the sea to the surface,” said Denise Hardesty, a principal research scientist at CSIRO and a member of the team analyzing the sediments. “Wherever you are, the organisms passing through those areas will have come in contact with it — whether it was a fishing line or a plastic bag that’s broken down into thousands of tiny pieces.”

“This is hundreds of kilometers offshore at a couple of kilometers of depth — that’s pretty confronting that, even there, we find it,” she added. “This stuff is everywhere.”

The sediments were analyzed using a red dye that causes any plastics to fluoresce under special light. The pieces detected were at least 10 micrometers wide — about the same width as very fine wool.

CSIRO scientists are doing further analysis and a scientific paper is being prepared for submission to a journal.

Microplastics have been found in several less remote seabed areas around Australia and other parts of the world.

CSIRO researchers last year reported that they had found plastic pieces in sediments taken from Derwent River in Tasmania. The same team has found plastic fibers in the digestive tract of mussels from the same river.

Jennifer Lavers, of the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania, said she was not surprised that plastic had been found in the bight “because there are multiple studies from around the world finding microplastics and even nanoplastics in sediments throughout the bottom of the world’s oceans.”

“Should it worry us? Absolutely! The smaller the pieces, the more species there are to consume it,” she said. “Everything that is tiny is at the base of the food web, so it’s not an issue of just an albatross swallowing a cigarette lighter or a sperm whale swallowing a big chunk of net, you now literally have microplastics being eaten by corals, sea cucumbers, clams and mussels, and zooplankton at the very base of the food web.”

“You have all levels of the food web infiltrated with this stuff,” she added. “Everywhere and anywhere that the plastic goes, the chemicals follow.”

Microplastics and microfibers are so ubiquitous in our air and water that the CSIRO researchers had to go to extreme lengths to reduce any contamination of their sediment samples from outside sources.

Equipment had to be pre-rinsed with deionized water, laboratory solutions had to be filtered, analysis took place in a fume hood and personnel wore clothes made from natural fibers. Air monitoring was also carried out to find laboratory areas with the least amount of airborne plastics.

A US$20 million four-year government and oil industry-backed research program into the bight ended last year and revealed a rich and previously unknown habitat on the deep seabed.

Jason Tanner is a marine biologist specializing in the ocean floor at the South Australia research and development institute. He helped lead the research into the biodiversity in the bight.

“There’s quite a diverse fauna down there — filter feeders, soft corals, sponges — and there are lots of more mobile organisms — starfish, sea cucumbers, urchins and, of course, fish,” he said. “We found almost 300 new species from our sampling.”

Tanner said that because plastics tend to sink in the ocean, it was logical that it would eventually settle into deep ocean sediments.

While taking samples of the bight seabed 3km down, they used a 4m trawl and “pretty much every time” they would bring up “human debris” to the surface, he said.

“We brought up Coke cans and bits of clothing,” he added.

The animals on the seabed used feeding methods that would likely cause them to eat any plastic that might be there “but what the impact of that would be, I couldn’t say,” Tanner said.

“It’s gutting to know that plastic pollution has been found in one of the wildest parts of our oceans,” Australian Marine Conservation Society marine campaigner James Cordwell said. “It is further evidence that few parts of our oceans are left untouched by plastic. We should be very concerned.”

The cool temperate waters of the Great Australian Bight “are some of the wildest and most amazing parts of our big blue planet,” where species such as southern right whales, bottlenose dolphins, Australian sea lions, great white sharks and little penguins lived, Cordwell said.

“This is further proof that the world needs to cut its plastic addiction and do much more to stop plastic pollution. Plastic pollution is flowing into our oceans at an alarming rate. Marine life gets entangled in it and mistakes it for food. Once ingested, it sticks in their stomachs and guts and can ultimately lead to their slow starvation,” he said.

“We need to lift our game in our response to plastic pollution. We’ve got the world’s third-largest ocean territory and we’re a rich, educated country who trades on our spectacular wild places,” he said.

“Cleaning up this mess at the bottom of the sea would be a monumental task and almost impossible. We’ve got to stop plastic reaching our oceans and entering our food chains,” he added.

Governments need to “legislate and incentivize,” he said, adding: “The longer we wait, the worse it gets. Australia must lead by example and change our domestic plastic consumption and help our neighbors do the same.”

It was “incredibly troubling” that plastics had penetrated to Great Australian Bight seabed, Greenpeace Australia Pacific oceans campaigner Nathaniel Pelle said.

“The communities of the bight are home to thriving tourism industries and fishing towns whose occupants cherish and depend on the health of this environment. The waters are so productive that fully 25 percent of the value of Australian seafood catches comes from the bight,” he said.

“Corporations like Nestle, Unilever and Procter & Gamble are still pushing incredible quantities of plastic on to the global market and governments in Australia and the world have been incredibly slow to act on controlling the avalanche,” he said.

“We cannot afford to continue our inaction toward this problem as plastic permeates every single part of the environment, from our drinking water and the food we eat to microplastic particles in the Antarctic and Great Australian Bight,” he said.

“Corporations and governments must move to not only limit the use and consumption of single-use plastics, but also to measure and address the impact of what is already in the environment,” he added.

Wilderness Society South Australia director Peter Owen said the Great Australian Bight was a “marine treasure” and governments around the world now needed to act on plastics.

“That microplastics have been found in the deep, remote waters of the Great Australian Bight is a wake-up call for better protection of our oceans and that includes protecting them from deep-sea oil and gas drilling that Norwegian oil giant Statoil wants to pursue in the Great Australian Bight,” he said.

South Australia was in 1977 the first state to introduce legislation that provides cash for returning recyclable plastics and introduced a plastic bag ban in 2009. Other states are only now introducing schemes to roll out this year and next year. Tasmania and Victoria have no plans to introduce such a scheme.

A South Australian government spokesperson said the state was “years ahead” of other areas in banning plastic bags and introducing its container deposit scheme.

“South Australia’s waterways and oceans have long been considered an asset that is important to protect and preserve. Container deposit schemes and plastic bag bans are recognized internationally as two of the most important ways that we can do this and both of these strategies are part of our behavior in South Australia,” the spokesperson said, adding that the state had a “longstanding culture of recycling and waste diversion.”

Members of the public could help by avoiding plastic wrapping “wherever practical and possible” and could also reduce the amount of plastic that they buy, reuse plastic containers and use recycling schemes.

The government “takes the problem of marine debris and its impacts on the environment and wildlife seriously,” Assistant Minister for the Environment Melissa Price said in a statement, citing her department’s threat abatement plan for the effects of marine debris on vertebrate marine life.

The plan has been in revision since early last year, with a public comment period ending in April last year.

According to a Department of the Environment and Energy spokesperson, the plan is still being revised with an expected release “in the second half of this year.”

Price said that responsibility for waste and litter management largely fell to the states, but added that the government would “continue to work with” state governments and businesses on the issue.

The public played an important role in cutting plastic waste on beaches and reducing their use of plastics by “choosing not to buy plastic products or choosing to buy products with less plastic packaging,” she added.

“[The public] can also support businesses that use products made of alternative materials to plastics and always take their waste away following visits to beaches and waterways,” she said.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s