The Iranian town of Doroud should be a prosperous place — nestled in a valley at the junction of two rivers in the Zagros Mountains, it is in an area rich in metals to be mined and stone to be quarried.

Last year, a military factory on the outskirts of town unveiled production of an advanced model of tanks.

Yet local officials have been pleading for months for the Iranian government to rescue its stagnant economy. Unemployment is about 30 percent, far above the official national rate of more than 12 percent. Young people graduate and find no work. The local steel and cement factories stopped production long ago and their workers have not been paid for months. The military factory’s employees are mainly outsiders who live on its grounds, separate from the local economy.

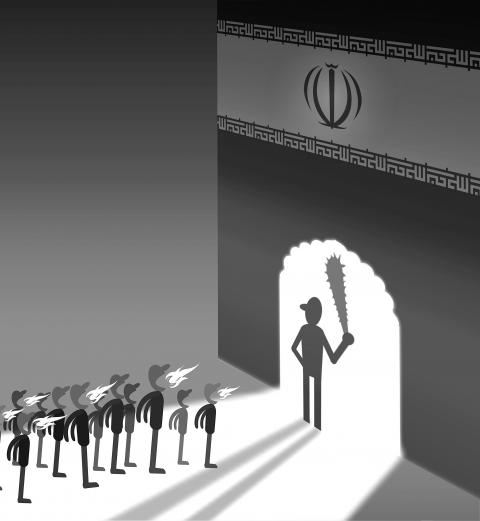

Illustration: Yusha

“Unemployment is on an upward path,” Majid Kiyanpour, the local parliament representative for the town of 170,000, told Iranian media in August last year. “Unfortunately, the state is not paying attention.”

That is a major reason Doroud has been a front line in the protests that have flared across Iran over the past week. Several thousand residents have been shown in online videos marching down Doroud’s main street, shouting: “Death to the dictator.”

At night, young men set fires outside the gates of the mayor’s office and hurl stones at banks. At least two people have been killed, reportedly when security forces opened fire. Overall, at least 21 people have died nationwide in the unrest so far.

Anger and frustration over the economy have been the main fuel for the eruption of protests that began on Dec. 28.

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, a relative moderate, had promised that lifting most international sanctions under Iran’s landmark 2015 nuclear deal with the West would revive Iran’s long-suffering economy.

However, while the end of sanctions did open up a new influx of cash from increased oil exports, little has trickled down to the wider population. At the same time, Rouhani has enforced austerity policies that hit households hard.

Demonstrations have broken out mainly in dozens of smaller cities and towns like Doroud, where unemployment has been most painful and where many in the working class feel ignored.

The working classes have long been a base of support for Iran’s hard-liners.

However, protesters have turned their fury against the ruling clerics and the elite Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, accusing them of monopolizing the economy and soaking up the country’s wealth.

Many protests have seen a startlingly overt rejection of Iran’s system of government by Muslim clerics. Under Iran’s Islamic Republic, in place since the 1979 revolution, the cleric-led establishment has considerable power over elected bodies like parliament and the presidency. At the top stands Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who has final say on all matters of state.

“They make a man into a god and a nation into beggars,” goes the cry heard in videos of several marches. “Clerics with capital, give us our money back.”

The initial spark for the protests was a sudden jump in food prices. It is believed that hard-line opponents of Rouhani instigated the first demonstrations in the conservative city of Mashhad in eastern Iran, trying to direct public anger at the Iranian president.

However, as protests spread from town to town, the backlash turned against the entire ruling class.

Further stoking the anger was the budget for the coming year that Rouhani unveiled in the middle of last month, calling for significant cuts in cash payouts established by Rouhani’s predecessor, hard-liner former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, as a form of direct welfare. Since he came to office in 2013, Rouhani has been paring them back. The budget also envisaged a new jump in fuel prices.

However, amid the cutbacks, the budget revealed large increases in funding for religious foundations that are a key part of the clerical state-above-the-state, which receive hundreds of millions of US dollars each year from the public coffers.

These foundations, including religious schools and charities, are tied closely to powerful clerics and often serve as machines for patronage and propaganda to build support for their authority.

As he announced the budget, Rouhani admitted that his government had no say over large parts of the spending and complained about the lack of transparency over the funds going to the foundations.

“They just take money from us,” he said. “If we ask: ‘Where did you spend the money?’ they say: ‘It’s none of your business. We spend it where we like.’”

Rouhani’s economic program has focused on trying to rein in government spending and build up the private sector and investment.

His policies have managed to pull inflation down from the high double-digits where it long stood, edging it back to 10 percent last month.

After the lifting of most sanctions in early 2016, the economy saw a major boost — 13.4 percent growth in the GDP in 2016, compared with a 1.3 percent contraction the year before, according to the World Bank.

However, almost all that growth was in the oil sector, where exports jumped from about 1 million barrels per day in 2015 to about 2.1 million barrels per day last year.

Growth outside the oil sector was at 3.3 percent.

Major foreign investment, which Rouhani touted as another benefit of opening to the world, has failed to materialize, in part because of continued US sanctions hampering access to international banking and the fear other sanctions could eventually return.

Iran’s official unemployment rate is at 12.4 percent, and unemployment among the young — those 19 to 29 — has reached 28.8 percent, according to the government-run Statistical Center of Iran.

The provinces “face more economic hardship,” wrote Brenda Shaffer, an adjunct professor at Georgetown University’s Center for Eurasian, Russian, and East European Studies. “Income levels and social services in the periphery are lower, unemployment rates are higher, and many residents suffer from extensive health and livelihood challenges emanating from ecological damage.”

The pain has been felt in the Iranian capital, Tehran, and other major cities as well.

However, there it has been more cushioned within a large middle class. Many can ignore those picking through trash for food.

However, in December 2016, Iranians, including Rouhani, expressed shock over a series of photographs in a local newspaper showing homeless drug addicts sleeping in open graves in Shahriar, on Tehran’s western outskirts.

“Things shouldn’t be so expensive that people have to cry out. It was because officials don’t care about people,” said one Tehran resident, Nasser Nazari, though he added that protests were not the way to react.

Associated Press writers Jon Gambrell and Nasser Karimi contributed to this report.

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

In an op-ed published in Foreign Affairs on Tuesday, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) said that Taiwan should not have to choose between aligning with Beijing or Washington, and advocated for cooperation with Beijing under the so-called “1992 consensus” as a form of “strategic ambiguity.” However, Cheng has either misunderstood the geopolitical reality and chosen appeasement, or is trying to fool an international audience with her doublespeak; nonetheless, it risks sending the wrong message to Taiwan’s democratic allies and partners. Cheng stressed that “Taiwan does not have to choose,” as while Beijing and Washington compete, Taiwan is strongest when