The past decade saw the end of cheap oil, the magic growth ingredient for the global economy after World War II. This summer’s increase in maize, wheat and soya bean prices — the third spike in the past five years — suggests the era of cheap food is also over.

Price increases in both oil and food provide textbook examples of market forces. Rapid expansion in the big emerging markets, especially China, has led to an increase in demand at a time when there have been supply constraints. For crude, these have included the war in Iraq, the embargo imposed on Iran and the fact that some of the older fields are starting to run dry before new sources of crude are opened up.

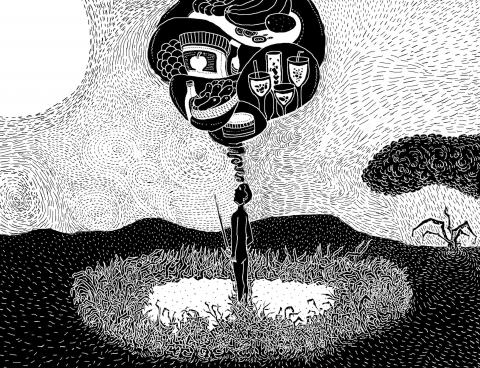

The same demand dynamics affect food. It is not just that the world’s population is rising by 1 percent a year. Nor is it simply that China has been growing at 9 percent a year on average; it is that consumers in the big developing countries have developed an appetite for higher protein western diets.

Meat consumption is rising in China, India and Brazil, and since it takes 7kg of grain to produce 1kg of beef (and 4kg to produce 1kg of pork), this is adding to global demand.

Farmers have been getting more efficient, increasing the yields of land under production, but this has been offset by two negative factors: policies in the US and the EU that divert large amounts of corn for biofuels and poor harvests caused by the weather.

If the World Bank’s projections are anything like accurate, further massive productivity gains from agriculture are going to be needed over the next two decades.

There will be an extra 70 million mouths to feed every year, which will result in a 50 percent increase in demand for food by 2030. Meanwhile, the amount of arable land per person will continue its long-term downward trend.

The extent of this challenge has been highlighted by the extreme drought in the US this year.

Failure of the maize harvest — down by more than 100 million tonnes on what was expected — has had a knock-on impact on wheat, which has not been affected by the lack of rain. Prices of both crops have jumped by US$100 a tonne this summer. The latest data from the World Bank showed that food prices rose 10 percent between June and July and have now exceeded the previous peak early last year.

It will take time for these increases to have their full impact on consumers. In the short run, the cost of meat will not be affected because there is glut caused by livestock owners slaughtering their herds to save money on expensive feed. However, by the end of the year, food will be dearer.

Central banks are unlikely to tighten policy in response to higher inflation, since the increase is seen as an external shock that will have a depressing effect on the spending power of consumers. They should not, however, assume that the spike will be a one-off, since grain stocks are at such low levels that bad harvests next year would see rocketing prices, probably accompanied by panic-buying, export bans and food riots.

A recent report from Oxfam said the US should expect further severe droughts in the coming decades.

“The US experienced US$14 billion disasters in 2011 — an historical record — including a blizzard, tornadoes, floods, a hurricane, a tropical storm, drought and heatwaves, and wildfires,” it said.

The current year has already seen wildfires, a windstorm, heatwaves in much of the country and the most severe drought in half a century.

This seems to be an apt moment for the West to reassess the wisdom of biofuels. The US ethanol distilleries used 120 million tonnes of maize last year, and there have already been calls from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization for the reduced maize crop to be used for human food.

There is also growing political opposition in the US to the country’s Renewable Fuel Standard, which mandates 57.5 billion liters of biofuels for this year, of which 50.7 billion liters can come from corn-based ethanol.

Unsurprisingly, livestock and poultry producers have been at the forefront of calls for the mandate to be suspended. The whole point about biofuels was that they were supposed to be a cost-free and a pain-free way for developed nations to show that they were responding to climate change. Rising crop yields meant there would be enough grain left over each year to turn into ethanol, and this would mean Western consumers could do their bit to save the planet without in any way compromising their living patterns. That now looks like a highly questionable assumption.

So what happens next? A lasting solution to the food question will require either action on the demand side, action on the supply side, or more likely both. The two obvious ways of limiting demand are to check population growth or to change dietary habits so that meat consumption is reduced. Neither is going to be easy to achieve.

On the supply side, the short-term response should be to find alternatives to biofuels. Longer term, the hope is that the pressures of a rising population, coupled with the incentives provided by rising food prices, lead to a second green revolution that will dramatically increase yields in those parts of the world — such as sub-Saharan Africa — where they are currently low. One of the few beneficial impacts of high commodity prices is that farmers will be able to afford to buy fertilizers for their land.

A recent study by Fidelity looked at some of the other recent developments to boost food supply, including precision agriculture — the use of high technology to apply the optimum amounts of seed, water and fertilizer for maximum efficiency — and a wider use of biotechnology and genetically modified crops. The report also highlighted what is known as “fast food” from animal cells, a process by which scientists “create artificial meat by delivering an electric charge to the animal muscle cells in a mixture of amino acids, which causes the cells to multiply.”

Given the predicted growth in consumption in developing countries, Fidelity says this could become an “environmentally acceptable option” as traditional meat becomes more expensive.

Whether this approach is “environmentally acceptable” remains to be seen. The Fidelity report does, however, clarify one point, namely that hard choices have to be made.

The current assumption seems to be that the world can have a rising population, ever-higher per capita meat consumption, devote less land to food production to help hit climate change targets and eschew the advances in science that might increase yields. This is the stuff of fantasy.

It is possible to have more intensive farming using the full range of technological breakthroughs in order to feed a bigger, meat-hungry population. Or it is possible to have lower yields from a more organic approach to feed a smaller population eating less meat. But not both.

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

The last foreign delegation Nicolas Maduro met before he went to bed Friday night (January 2) was led by China’s top Latin America diplomat. “I had a pleasant meeting with Qiu Xiaoqi (邱小琪), Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping (習近平),” Venezuela’s soon-to-be ex-president tweeted on Telegram, “and we reaffirmed our commitment to the strategic relationship that is progressing and strengthening in various areas for building a multipolar world of development and peace.” Judging by how minutely the Central Intelligence Agency was monitoring Maduro’s every move on Friday, President Trump himself was certainly aware of Maduro’s felicitations to his Chinese guest. Just