It was bad enough that Ma Chi was driving well above the speed limit on a downtown boulevard when he blew through a red light and struck a taxi, killing its two occupants and himself. It did not help, either, that he was at the wheel of a US$1.4 million Ferrari that early morning in May, or that the woman in the passenger seat was not his wife.

However, what really set off a wave of outrage across this normally decorous island-state is the fact that Ma, a 31-year-old financial investor, carried a Chinese passport, having arrived in Singapore four years earlier.

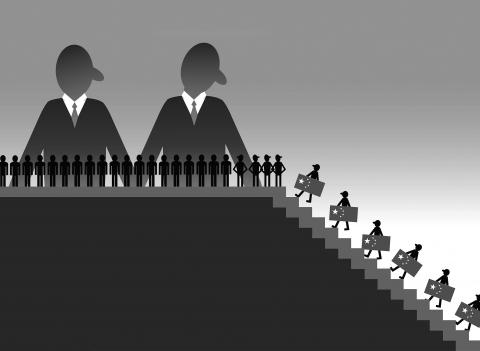

The accident, captured by the dashboard camera of another taxi, has uncorked long-stewing fury against the surge of new arrivals from China, part of a government-engineered immigration push that has almost doubled Singapore’s population to 5.2 million since 1990. About 1 million of those newcomers arrived in the past decade, drawn by financial incentives and a liberal visa policy aimed at counteracting Singapore’s famously low birthrate.

Tensions over immigration bedevil many nations, but what makes the clash in Singapore particularly striking is that most of the nation’s population was already ethnic Chinese, many of them the progeny of earlier generations of Chinese immigrants. The paradox is not lost on Alvin Tan, the artistic director of a community theater company that takes on thorny social issues.

“Mainlanders may look like us, but they aren’t like us,” said Tan, who is of mixed Malay-Chinese descent and does not speak Mandarin. “Singaporeans look down on mainlanders as country bumpkins, and they look down on us because we can’t speak proper Chinese.”

These days, mainland Chinese get blamed for driving up real-estate prices, stealing the best jobs and clogging the roads with flashy European sports cars. Coffee shop patrons gripe that they need Mandarin to order their beloved Kopi-C (coffee sweetened with evaporated milk). True or not, tales of Chinese women stealing away married men have become legion.

“Singaporeans woke up one day to find the trains more crowded with people who speak Mandarin, and they aren’t handling it very well,” said Jolovan Wham, executive of an organization that helps foreign laborers, many of whom face exploitive work conditions. “The amount of xenophobia we’re seeing is just appalling.”

In the days after the accident, social media were awash in commentary that blamed mainlanders like Ma for upending Singapore’s well-mannered ways. Bloggers called him “spoiled and corrupt,” wrongly identified him as the son of a powerful Beijing official and suggested the police prosecute him posthumously. Detractors created a mock Facebook page, since removed, that brimmed with ugly invective.

“Good riddance and enjoy hell you piece of mainland trash,” read one of the tamer postings.

Singapore’s government, which has long relied on strict media and sedition laws to maintain ethnic and religious harmony in a multicultural society, has become alarmed by the venom, much of it coming from middle-class Singaporeans. In a recent speech to a parliamentary committee, Singaporean Deputy Prime Minister Teo Chee Hean (張志賢) defended the country’s immigration policies, saying foreign workers — both educated and unskilled — were indispensable to counterbalance a rapidly aging population and to maintain the momentum of Singapore’s roaring economy.

“Quite naturally, we expect that our new immigrants should adapt to our values and norms, and we get upset if they have not yet done so,” he said, speaking in English, Singapore’s lingua franca. “However, I do agree that we should not let recent reactions towards new immigrants and foreigners undo the good job that we have done in building a strong and cohesive society out of people from many lands.”

More than a third of Singapore’s residents are now foreign-born. While the government has refused to release figures on immigrant origins, officials are quick to stress that the majority of new citizens came from countries other than China, with nearly half from Southeast Asia.

In private, they also note that many of the more outlandishly wealthy arrivistes are just as likely to hail from London, Dubai or New Delhi as from China. Among them is Eduardo Saverin, the Brazilian-born co-founder of Facebook whose decision to trade his US passport for Singaporean residency provoked a tempest in Washington this year.

The issue nonetheless looms large on the political landscape, and many analysts say anger over immigration contributed to the governing People’s Action Party’s unexpected losses in last year’s parliamentary elections.

The government has started to adjust the spigot. The number of new permanent residents has decreased by nearly two-thirds since 2008, when 80,000 applications were accepted, while the number of people granted citizenship has remained level at about 18,500 a year, according to the National Population and Talent Division. Despite the growing animus, Singapore remains the third most desirable immigration destination for affluent Chinese after the US and Canada, according to a survey by the Bank of China and the Hurun Report, which compiles an annual list of the richest Chinese.

Although the backlash has largely been confined to the anonymity of the Internet, Singaporeans staged a rare public protest against new immigrants last summer after a family from China complained about the curry-laden odors wafting from an ethnic Indian neighbor’s apartment. A campaign organized via Facebook drew tens of thousands of supporters who all vowed to cook a curried dinner on the same day.

There was another wave of schadenfreude in March this year, after a Chinese student at the National University of Singapore was fined S$3,000 (US$2,390), for referring to Singaporeans as dogs in a posting on a Chinese microblog service. The student, who was also forced to perform three months of community service and to return a semester’s worth of financial aid, said he was upset by the glares from elderly Singaporeans he accidentally jostled on the sidewalk.

The tenor of the debate has unnerved some Chinese immigrants, and angered others. Wang Quancheng, chairman of the Hua Yuan Association, the largest organization representing mainlanders, said the government was not doing enough to help integrate new arrivals, but he also blamed Singaporeans for their intolerance and said many were simply jealous that so many Chinese immigrate here with money in their pockets.

“Of course, the new arrivals are rich or else the government would have to feed them,” he said. “Some locals are very lazy and live off the government. When new immigrants come, they think it is competition, taking away their rice bowls.”

Actually, the typical Singaporean is far better off than the average person in China. Thousands of Chinese students live here, too, some with mothers who came along to support their children by illegally working as maids, or worse. In Geylang, Singapore’s red light district, Chinese women can sometimes outnumber the stalwarts from Thailand and the Philippines.

Many Chinese do successfully assimilate. According to official figures, 30 percent of all Singaporean marriages involve a citizen and a foreigner, up from 23 percent a decade ago. However, the passage of time does not necessarily narrow the cultural gap.

Yang Mu, a Beijing-born economist who moved here in 1992 and became a citizen three years later, acknowledges a host of superficial differences, saying he finds locals somewhat aloof, more likely to work late and less likely to spend the night commiserating over stiff drinks. Unlike Singaporeans, people from China, he said, would never split a dinner tab.

“I’ve voted in four elections now, and it is great to live in a country where you can trust people and trust the government,” said Yang, 66, who formed a local charity that teaches English to Chinese migrants.

“I still don’t feel Singaporean,” he added. “The truth is, when I retire, I’ll probably move back to China.”

In the first year of his second term, US President Donald Trump continued to shake the foundations of the liberal international order to realize his “America first” policy. However, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty and unpredictability, the Trump administration brought some clarity to its policy toward Taiwan. As expected, bilateral trade emerged as a major priority for the new Trump administration. To secure a favorable trade deal with Taiwan, it adopted a two-pronged strategy: First, Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing” chip business from the US, indicating that if Taipei did not address Washington’s concerns in this strategic sector, it could revisit its Taiwan

The stocks of rare earth companies soared on Monday following news that the Trump administration had taken a 10 percent stake in Oklahoma mining and magnet company USA Rare Earth Inc. Such is the visible benefit enjoyed by the growing number of firms that count Uncle Sam as a shareholder. Yet recent events surrounding perhaps what is the most well-known state-picked champion, Intel Corp, exposed a major unseen cost of the federal government’s unprecedented intervention in private business: the distortion of capital markets that have underpinned US growth and innovation since its founding. Prior to Intel’s Jan. 22 call with analysts

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

International debate on Taiwan is obsessed with “invasion countdowns,” framing the cross-strait crisis as a matter of military timetables and political opportunity. However, the seismic political tremors surrounding Central Military Commission (CMC) vice chairman Zhang Youxia (張又俠) suggested that Washington and Taipei are watching the wrong clock. Beijing is constrained not by a lack of capability, but by an acute fear of regime-threatening military failure. The reported sidelining of Zhang — a combat veteran in a largely unbloodied force and long-time loyalist of Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) — followed a year of purges within the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA)