It was once the unspoiled jungle home for tigers, elephants, bears and gibbons. However, today, Botum Sakor National Park in southwest Cambodia is fast disappearing to accommodate a much less endangered species: the Chinese gambler.

“This was all forest once,” said Chut Wutty, director of the Natural Resource Protection Group, an environmental watchdog based in the capital, Phnom Penh, gesturing across a near-treeless landscape. “But then the government sold the land to rich men.”

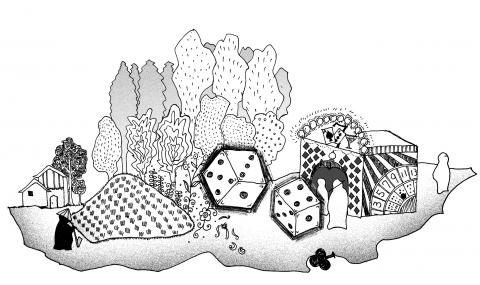

He means Tianjin Union Development Group, a real-estate company from northern China, which is transforming 340km2 of Botum Sakor into a city-sized gambling resort for “extravagant feasting and revelry,” its Web site said. A 64km highway, now almost complete, will cut a four-lane swathe through mostly virgin forest.

National parks and wildlife sanctuaries in Cambodia, an impoverished country known for its ancient temples and genocidal Khmer Rouge regime of the 1970s, could soon vanish entirely as deep-pocketed Chinese investors accelerate a secretive sell-off of protected areas to private companies, said Chut Wutty and other activists.

The land sales also point to another trend: the expansion of Chinese economic interests in Southeast Asia’s undeveloped frontiers, which comes at a delicate time as tensions simmer over China’s sovereignty claims in the disputed South China Sea and the US vows to re-engage with the region.

Last year, the Cambodian government granted so-called economic land concessions to scores of companies to develop 7,631km2 of land, most of it in national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, according to research by the respected Cambodia Human Rights and Development Organization.

The area of concessions granted has risen six-fold between 2010 and last year, partly a reflection of booming Indochina trade as China’s economic influence spreads deeper into Southeast Asia.

Foreign conservation groups in the country have remained silent about the sell-off for fear of wrecking their relationship with the government of mercurial Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen. However, Cambodians dislodged from concession areas are starting to find their voices.

Fishing families in Botum Sakor say that Union Group is using strong-arm tactics to relocate them deep inland.

“It’s been my land since my grandparents’ generation,” said Srey Khmao, 68, from Thmar Sar. “I lived peacefully there until Union Group threatened the villagers and told them to remove their belongings.”

Such protests could ratchet up anti-Chinese sentiment in Cambodia, where China is both the largest foreign investor and source of foreign aid. That aid, often in the form of no-strings-attached infrastructure projects, has made Hun Sen less reliant on Western donors, who generally demand greater transparency and respect for human rights.

It has also eroded the influence of foreign conservation groups in Cambodia, many of whom work in the same protected areas now being sold off. Their criticism has remained muted for fear Hun Sen will do what he did to British environmental watchdog Global Witness in 2005 and kick them out.

“The days of donor-dependency are over,” said a foreign conservationist working in Cambodia, who asked not to be identified. “Much more money is coming into this country through direct investment, especially from Chinese companies, so the carrot-and-stick incentive that NGOs [non-governmental organizations] might have had 10 years ago isn’t as powerful these days.”

Land-grabbing, illegal logging and forced evictions have long been common in Cambodia, but by granting land concessions, the government has effectively legalized these practices in the country’s last remaining wilderness, activists say.

Companies from Cambodia, Vietnam and other countries are also exploiting the land sell-off, mainly to develop rubber plantations and other agribusinesses. However, the most lucrative projects — mining for gold and other minerals — are dominated by the Chinese, the Cambodian Center for Human Rights said.

Cambodia’s 2001 land law forbids economic land concessions greater than 10,000 hectares, but China’s Union Group won a 99-year lease thanks to a 2008 royal decree that carved out 36,000 hectares from Botum Sakor and redefined it.

In the same year, a contract was signed by Cambodian Environment Minister Mok Mareth and the chief of Union Group’s board of directors, Li Zhi Xuan. The company was granted a further 9,100 adjoining hectares last year to build a hydroelectric dam.

Union Group has big ambitions for the area, including a network of roads, an international airport, a port for large cruise ships, two reservoirs, condominiums, hotels, hospitals, golf courses and a casino called “Angkor Wat on Sea,” according to the contract and its Web site.

It will sink US$3.8 billion into its Botum Sakor resort, a figure quoted to rights groups last month by Koh Kong Province Governor Bun Leut. It covers an area almost half the size of Singapore. People in the area say it will be called either “Seven-headed Dragon” or “Hong Kong II.”

“Those are just rumors. It hasn’t been named yet,” said Cheang Sivling, a Chinese-speaking Cambodian manager for Union Group’s road-building operations.

The four-lane highway, built at a cost of about US$680,000 per kilometer, is part of a system of roads Union Group will run across Botum Sakor, Cheang Sivling added.

This alarms Mathieu Pellerin, a researcher with the Cambodian human rights group Licadho, who said that newly built roads give logging operators greater access and could accelerate the destruction of forests.

“Botum Sakor is melting away,” he said.

The work sites along the highway house a number of Chinese engineers and are guarded by Cambodian soldiers.

Access to the resort area itself is blocked by a provincial park ranger who, when journalists tried to pass, threatened to radio for back-up from military police, who along with the police routinely provide security for big concessionaires.

“This is China,” he said firmly.

Nearby, at the picturesque seaside village of Poy Jopon, people were preparing to leave after signing away their property to Union Group — under duress, they say.

“I’m upset, but there is nothing I can do about it,” said Chey Pheap, 42, a grocery store owner. “This is the way society works.”

He and the remaining villagers will soon be moved to houses about 10km inland.

When asked to describe the new area, one of Chey Pheap’s neighbors said: “No work, no water, no school, no temple. Just malaria.”

Nhorn Saroen, 52, was among hundreds of families who have already been moved from another fishing village, called Kom Saoi.

“We were told it was Chinese land and we couldn’t cut down a single tree,” he said. “Some people refused to leave. Their land was taken and now they have nothing.”

He was provided with a house in a purpose-built village far inland, robbing him of his main livelihood: fishing. The houses surrounding Nhorn Saroen’s are deserted. Many families cannot make ends meet in the remote area and have moved away, he said.

Passing just behind his house was a moat which delineated Union Group’s land. It was 3m deep and twice as wide, and ran for many kilometers. For the villagers, it symbolized China’s power and remoteness.

“Even though we hate the Chinese, what can we do?” Nhorn Saroen said.

Union Group’s Web site praises Cambodia for its “sound public order” and “simple and honest” people.

Allegations of forced evictions are “a problem between the Cambodian government and its people,” said a company spokeswoman, who declined to be identified.

Union Group obeyed Cambodian laws and worked closely with the Chinese government, she added. Its road network was welcomed by people in the area.

“Residents said they finally saw real roads and cars,” she said. “In this regard, I think we have contributed to Cambodia.”

She confirmed that Union Group is spending “billions” of dollars on the project.

The government granted a record number of economic land concessions last year, said Pellerin, but keeping track of them is impossible. Information on hard-to-reach concessions or the firms leasing them is not systematically maintained.

The government’s contract with Union Group is “shocking,” Pellerin said. “Cambodia is giving away 36,000 hectares to a foreign entity with little if any oversight or obvious benefit to the people.”

As part of that contract, Union Group deposited US$1 million with the Council for the Development of Cambodia, but pays no fees for the first decade of its lease.

Leasing protected areas generates minimal money, said Sem Saroeun, director-general of finance and administration at the Ministry of Environment. The government charged even deep-pocketed Chinese firms a mere US$1 per hectare per year.

“This is a voluntary price and the funds go to the protection and conservation of the environment,” he said.

New anti-graft laws prevent additional under-the-table payments, he added.

However, Seng Sok Heng of Community Peace Network, a group which helps track land concessions for the pro-transparency Web site Open Development Cambodia, said the government is charging up to US$10 per hectare per year and that additional bribes were common.

Environment official Sem Saroeun said he didn’t know the total area leased out by the government, but added that concessions were only granted on land surrounding protected areas.

“The core areas are still protected,” he said.

However, this claim is upended not only by Reuters’ trip to fast-shrinking Botum Sakor, but also by satellite images and research by groups. Maps produced by Licadho show huge leaseholds at the heart of wildlife sanctuaries, such as Boeng Per and Phnom Aural, while 19 concessions have swallowed up almost all of Virachey national park on Cambodia’s remote border with Laos and Vietnam.

With Chinese investors fanning out across fast-growing Southeast Asia, festering resentment over land-hungry projects could spell trouble for Beijing, especially after the US signaled last year that it would strengthen economic and diplomatic influence in the region.

A new generation of Chinese multinationals is facing pockets of resistance in a region they once dominated without question.

Myanmar’s reformist government apparently bowed to popular discontent by canceling a US$3.6 billion Chinese-led dam project in September, marking a turning point in relations with its giant neighbor. A similar movement opposes trans-Myanmar pipelines that will transport oil and gas to China.

Through all this, Cambodia has been a reliable ally for China. Foreign direct investment from China was US$1.19 billion last year, almost 10 times that of the US, estimated the government’s Council for the Development of Cambodia, which Hun Sen chairs.

China has also been generous with aid, pledging more than US$2 billion since 1992, mostly in soft loans, Cambodian Finance Minister Keat Chhon said last month.

This “blank-check diplomacy” threatened to “erode donor efforts to use assistance to promote improved governance and respect for human rights,” a US diplomat said in a cable released last year by the anti-secrecy group WikiLeaks.

“There is a growing sense — and this is not unique to Cambodia — that Chinese investors and employers are problematic,” said Sophie Richardson, Asia advocacy director for Human Rights Watch. “At the same time, it’s not as if the Cambodian government is stepping up to defend its own citizens.”

Hun Sen has publicly praised China for placing no conditions on its aid, but the US diplomat said in the cable that Chinese companies had been rewarded with non-transparent “access to mineral and resource wealth.”

And land: Leaseholds offer potentially strategic locations for expanding Chinese interests. Union Group’s vast concession has easy access to both the Gulf of Thailand — the traditional backyard of US military ally Thailand — and the hotly contested South China Sea.

For Chut Wutty, Union Group’s activities smack of colonization.

“You think after 99 years that this land will be returned to Cambodia? You think they’ll kick the Chinese out? No way. It’s forever,” Chut Wutty said.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its