Regional integration is usually regarded as a way for countries to strengthen themselves. But today’s efforts at regional integration in Latin America seem to have a different purpose altogether. They are put forward to help the proponents of various plans jockey for power and influence on both the regional and global stage.

Indeed, none of the current initiatives to boost Latin American regional integration resemble at all the European integration process. Nor can they be considered the first tentative steps towards such a shared destiny, in the manner of the 1952 European Coal and Steel Community Treaty, which began the project for European unity.

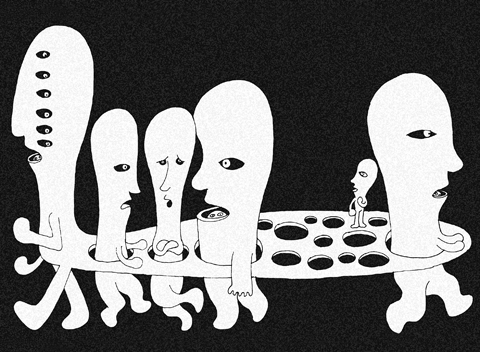

At first glance, the almost constant bombardment of integration proposals makes it appear as if the region’s presidents are trying to outdo each other in seeing who can come up with the greatest number of proposals. All the while, scant attention is paid to the region’s already established bodies, which are in sad shape.

Consider MERCOSUR (Mercado comun del sur, or Southern Common Market), the main post-Cold War regional initiative.

The Argentine academic Roberto Bouzas says MERCOSUR is in a critical state of affairs, owing to the inability of its institutions to maintain “the common objectives which drove its member states to engage in the process of regional integration and the consequent loss of focus and capacity to prioritize underlying political problems.”

Similar diagnoses are made with respect to the Latin American Economic System, the Andean Community of Nations and other regional organizations.

Contributing to this loss of dynamism is the flood of proposals rushing out of Venezuela, including the Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas, the Trade Treaty of the Peoples, the Bank of the South, and the South Atlantic Treaty Organization. Some of the Venezuelan initiatives are going nowhere, but others, such Petrocaribe, Petrosur and TeleSUR, are taking off.

Meanwhile, Brazil is intent on assuming a regional and global political role that corresponds to its growing economic weight. The challenge is to find a regional role that is compatible with Brazil’s size, but that does not create mistrust and, at the same time, benefits the rest of the region.

The proposed Union of South American Nations (Unasur), like the South American Defense Council, is part of a Brazilian regional strategy to encourage cooperation within Latin America in order to counterbalance the power of the US and act as a mediator in regional disagreements. While the Unasur proposal may have been formulated in a more rigorous way than other initiatives, its failure to contemplate trade integration means that there is nothing to tie member states together beyond political will.

Discussions about international free trade, however, have generally been held outside the region, in Doha or in the G20, with Argentina, Brazil and Mexico representing Latin America. Although Unasur aims to progress beyond free-trade agreements, this requires a more streamlined integration within the organization — one that expands its current role as a forum for discussing problems and seeking solutions for Latin America as a whole.

Unasur, however, has highlighted the cooling of relations between Brazil and Mexico, which is not a member of the new organization. This may well have an impact on future regional political coordination, although Mexico’s future membership has not been ruled out. (Furthermore, Mexican President Felipe Calderon’s participation in the Latin American and Caribbean Summit on Integration and Development in Bahia in December 2008 suggests that Mexico has not turned its back on the possibility of coordinating regional positions.)

The South American Defense Council, however, has stalled. To increase its effectiveness, the mistrust that permeates Unasur must be quelled and the goals of member states must be more clearly defined. This is especially true of Brazil, the source of much of this mistrust.

Finally, Ecuadoran President Rafael Correa proposed some time ago an Organization of Latin American States to replace the Organization of American States (OAS). Although the inclusion of all Latin American states goes some way toward repairing the weakened Brazilian-Mexican axis, and creates a new and more positive environment for future political coordination, this new organization is unlikely to contribute much to actual regional integration.

The lack of regional common policies is particularly noticeable in the areas of regional defense and internal security, where it has been impossible to identify a common position on inter-state tensions, the fight against organized crime and drug trafficking. These difficulties are exacerbated by the OAS’ inability to address complex situations such as the coup d’etat in Honduras, the conflict between Ecuador and Colombia or broader regional problems.

This regional stasis may worsen as a result of growing nationalism; an increase in social divisions within states; weapons proliferation and an increase in military spending; and environmental degradation. It seems that Latin America has abandoned the principles, commitments and foundations of full regional integration. Indeed, national interests and nationalistic egos have now moved to center stage.

Augusto Varas is president of the EQUITAS Foundation in Chile.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

In the first year of his second term, US President Donald Trump continued to shake the foundations of the liberal international order to realize his “America first” policy. However, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty and unpredictability, the Trump administration brought some clarity to its policy toward Taiwan. As expected, bilateral trade emerged as a major priority for the new Trump administration. To secure a favorable trade deal with Taiwan, it adopted a two-pronged strategy: First, Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing” chip business from the US, indicating that if Taipei did not address Washington’s concerns in this strategic sector, it could revisit its Taiwan

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,

Taiwan’s long-term care system has fallen into a structural paradox. Staffing shortages have led to a situation in which almost 20 percent of the about 110,000 beds in the care system are vacant, but new patient admissions remain closed. Although the government’s “Long-term Care 3.0” program has increased subsidies and sought to integrate medical and elderly care systems, strict staff-to-patient ratios, a narrow labor pipeline and rising inflation-driven costs have left many small to medium-sized care centers struggling. With nearly 20,000 beds forced to remain empty as a consequence, the issue is not isolated management failures, but a far more