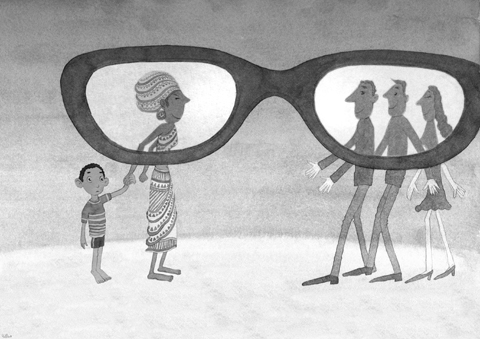

With AIDS, malaria and other diseases costing millions of lives every year, worrying about the vision of people in the developing world may seem like an indulgence.

But supplying glasses for the world’s poor may be one of the most valuable investments around. Hundreds of millions of people — some put the estimates as high as 2 billion — do not have the corrective lenses that would allow them to lead better, more productive lives.

A study published in a WHO journal in June estimated the cost in lost output at US$269 billion a year. Moreover, tackling vision problems early can help prevent later blindness.

Now efforts are under way to find a means of distributing inexpensive glasses on a wide scale. One promising technology is self-adjustable spectacles, which let untrained wearers set the right focus themselves in less than a minute, greatly reducing the need for trained optometrists, who are rarely available in Africa and many parts of Asia. Though these adjustable glasses cannot yet help with conditions like astigmatism, about 90 percent of refractive errors can be fixed.

At least three organizations are now offering their own versions of low-cost adjustable spectacles. Two are relatively new groups based in the Netherlands that have received little international recognition. The third, based in England and championing a British invention called AdSpecs, has been attracting widespread media attention for more than a decade.

AdSpecs, which allow the corrective power of the glasses to be adjusted by means of a clear fluid injected into the lenses, were developed by Joshua Silver, a physics professor at Oxford University who has retired and now directs a research institute there called the Center for Vision in the Developing World. Since introducing the glasses in 1996, Silver has set an ambitious goal of distributing a billion pairs of low-cost adjustable glasses by the year 2020.

In the intervening 13 years, though, only about 30,000 AdSpecs have been distributed; they cost about US$19 a pair.

One of the Dutch groups, the Focus on Vision Foundation, says it can produce its Focusspec glasses for about US$4 a pair. The group’s founders say the price will drop substantially once the glasses are being made in large volume. They plan to distribute about 30,000 pairs early this year, initially in Afghanistan, Ghana and Tanzania.

The other Dutch offering, called U-Specs (universal spectacles), is being promoted by the VU University Medical Center and a charity called the DOB Foundation.

Both Dutch models are based on a design pioneered in the 1960s by Luis Alvarez, an American who won a Nobel Prize in physics. The design uses two lenses that slide across each other to alter their focus. U-Specs were initially developed in 2003 by Rob van der Heijde, a physicist at the VU University Amsterdam.

Frederik van Asbeck, a former student of van der Heijde, struck out on his own to develop the Focusspec in 2005. Though the Dutch camps have had sporadic contact, they are not working together.

The tangled provenance of the designs demonstrates the unspoken yet occasionally palpable sense of rivalry among the various camps.

“I view them as good friends,” Silver, the AdSpecs inventor, said. “We’re not competitors. I’m just rather keen on origins and facts being clearly stated.”

He said they all agreed that the developing world needed a “low-cost design that can be produced at very high volume,” conceding that “none of the enterprises around today can do that.”

But each camp is convinced that it has the best approach to supply the millions or even billions of inexpensive glasses the developing world needs.

Focus on Vision says its advantage is the injection-molding process that allows its Focusspec eyeglasses to be made cheaply. It was developed by a Dutch engineer, Ron Kok, who grew wealthy in the 1980s by streamlining the manufacture of compact discs and contact lenses.

Focus on Vision invited Kok to work that same magic on its glasses.

“I saw immediately that you could make it simpler,” he said. “They’re designed to be easy and cheap to produce.”

The U-Specs team emphasizes its scientific pedigree.

“We took more of an academic approach, or at least a scientific approach, rather than an entrepreneurial one,” said Sjoerd Hannema, who was in charge of the U-Specs project until the middle of last year.

“Having a university and an eye hospital behind it,” he said, “helps build recognition and authority around this project.”

Hannema now leads a nonprofit organization called Adaptive Eyewear, which is running a distribution project in Rwanda called Vision for a Nation. It uses a combination of U-Specs, AdSpecs and traditional reading glasses.

Although they are not made using Kok’s special production technique, supporters of U-Specs say they will ultimately cost about the same to produce as the Focusspec.

“It will be around one to two dollars, depending on the quantity,” Hannema said. “If you make a million glasses, then automatically your cost price goes down dramatically. But then the challenge is where are you going to bring those glasses? Ultimately the cost of distribution is what matters.”

“They’re basically all at the same level,” he said, “and at the first stage of a very complicated journey.”

The Focusspec team contends that it is the closest to reaching mass production.

“I think we’re the furthest,” said Ben van Noort, an ophthalmologist who is president of Focus on Vision. “But we’ll see. As soon as we make a million per year, the price will drop to a euro.”

He suggested that fluid-based spectacles, like those promoted by Silver, were more sensitive to shifts in temperature, which made them less stable, especially in the challenging climates where many of these glasses are to be distributed.

Yet the Focusspec has also had its early problems. In a recent visit to the production facility in Veghel, which is about 80km southeast of Amsterdam, the adjustment wheel was not working properly on a large batch of glasses. They had to be repaired before they could be sent to Afghanistan, where they were eventually to be distributed by Dutch soldiers stationed there.

“Once you start to produce them on a large scale, you bump into things like this,” van Noort said. “It’s trial and error. There’s no handbook for this.”

Silver said his fluid-filled spectacles would eventually cost less as well.

“The Focus on Vision work is very interesting in that it shows that significant cost reduction is possible,” he said. “But from my perspective, the jury is still out. There’s no reason why Alvarez would be cheaper” in the long term.

When it comes to choosing sides, many of the charitable groups involved say they are open to whatever glasses do the job. J. Kevin White, a former Marine who runs Global Vision 2020, a foundation that distributes adjustable glasses, said fluid-filled lenses generally offer better optical quality and correct a greater range of refractive error. The Alvarez designs, by contrast, are cheaper, smaller, better-looking and less likely to break.

For his part, Hannema considers the occasional strife between the groups to be counterproductive.

“Kids in India don’t benefit from that,” he said. “It’s like if UNICEF and the Red Cross would quarrel about a patent on a medicine from a hundred years ago.”

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the