At dusk, Sergeant Levente Saja stands in the open countryside and scans the horizon through binoculars. A dirt road separates a field of maize from a wide expanse of scrub and grass.

“This corn makes our job a lot more difficult,” he said.

The cornfield is in Hungary, a member of the EU and part of the Schengen Zone, which stretches west to Portugal and north to Scandinavia with no internal border checks or further passport scrutiny.

The other field is in war-scarred Serbia, which is not an EU member and where the Balkan ethnic conflicts of the 1990s left the economy and much of its infrastructure in ruins.

Serbia has become one of the main land routes into the EU for those in search of a better life but lacking the documents to enter legally.

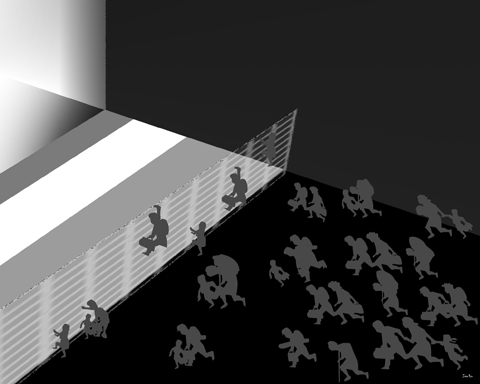

Day and night, men, women and children crawl, run, shuffle and crouch, inching their way across the fields towards Hungary. Saja and his colleagues in the Hungarian border police are tasked with stopping these illegal migrants.

“You never know when they might turn up,” he said.

The Hungary-Serbia border is just one more barrier on a very long journey. Many will have spent months traveling, often on foot, living in unimaginable conditions.

Saja recalls finding an Afghan man just inside the Hungarian border: “He was lying in a field, exhausted, unconscious.”

After receiving medical treatment, the Afghan requested political asylum, making him the responsibility of the Interior Ministry’s Office of Immigration and Nationality.

Most of those apprehended on the “green border,” as it is known, are Roma, or gypsies, from Serbia, and Kosovo Albanians. Africans appear periodically and in recent months the number of Afghan refugees has noticeably increased, said border police officer Major Szabolcs Revesz.

“Hungary is still not a target country for illegal immigrants,” said Lieutenant Colonel Gabor Eberhardt in his office at police headquarters in the university town of Szeged, southern Hungary.

Last week, the EU border control agency Frontex said illegal border crossings into the EU declined by 20 percent in the first half of this year, largely due to stronger border controls and the economic crisis.

However, the agency noted that illegal immigration into Hungary has climbed exponentially.

Eberhardt said: “Most who cross the border illegally are heading for Germany, Switzerland or other wealthier countries.”

His department patrols 62km of Hungary’s border with Serbia and its 68km border with Romania, containing five official border crossings.

Since joining the Schengen Zone in January last year, Hungary has emerged as an attractive destination for migrants keen to get into Western Europe without the proper papers. This rising demand, coupled with the stepped-up security, is reflected in the prices charged by criminal gangs that provide false papers and transport.

“People traffickers in Kosovo used to charge 1,500 euros (US$2,200). Now they are demanding 3,000 euros,” Eberhardt said.

In practice, this fee will often only get the migrant as far as the border: “Clients” are told to split up and make their own way into Hungary before regrouping. This is when they are usually picked up by border police and either sent back to Serbia or into the slow system for processing asylum claims.

Many, who might have already handed over every cent they had for transport to the West, are simply abandoned in Hungary, sometimes even told that they are already in Switzerland or Germany.

Others make their own way on foot, often following railway lines or the few roads that are the only landmarks in the remote, open countryside.

“As some illegal migrants are on the verge of death when we find them, the first thing we have to do is provide them with medical attention,” Eberhardt said.

Border guards insist that it seems impossible to know how many are making it into Hungary illegally, but Eberhardt is confident the number is low.

“I cannot say we are detecting 100 percent of illegal border crossings, but somewhere very close to that,” he said.

The strip of border under Eberhardt’s watch is just one of five stretches of Hungary’s external Schengen borders with neighboring Ukraine, Romania, Serbia and Croatia.

“Although 836 were officially caught in the green border in 2008, the real number of people is probably closer to 2,500,” he said.

The figures only tell part of the story: Children are not included in the official statistics on illegal immigration.

Eberhardt points to a room for mothers and children in the Szeged headquarters, where those apprehended are processed and either returned or sent into the asylum system. The grimness of the barred door and linoleum floor are eased only slightly by a few colorful posters on the wall, rubber play mats and a television.

Officially, more than 900 migrants had been picked up by the end of August, already more than last year’s total. And these were just those caught on Hungary’s part of the Schengen land border, which runs from the tip of Norway inside the Arctic Circle down to Slovenia on the Adriatic.

Saja, the genial sergeant, knows the “green border” like the back of his hand, including which drainage ditches and rows of bushes migrants use for cover.

Despite thermal-imaging cameras and helicopter backup — the EU has poured millions into tightening its expanded eastern border — he and his colleagues more often use simple hunters’ tricks. Inadvertently moving a seemingly innocent branch can betray a migrant’s passage to the guards.

Although they will sometimes try to evade capture by fleeing — into the cornfields, for example — once caught, the illegal migrants are usually passive and put up little resistance.

“They don’t try to fight,” Saja said. “They are usually pretty worn out anyway.”

A failure by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to respond to Israel’s brilliant 12-day (June 12-23) bombing and special operations war against Iran, topped by US President Donald Trump’s ordering the June 21 bombing of Iranian deep underground nuclear weapons fuel processing sites, has been noted by some as demonstrating a profound lack of resolve, even “impotence,” by China. However, this would be a dangerous underestimation of CCP ambitions and its broader and more profound military response to the Trump Administration — a challenge that includes an acceleration of its strategies to assist nuclear proxy states, and developing a wide array

Twenty-four Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers are facing recall votes on Saturday, prompting nearly all KMT officials and lawmakers to rally their supporters over the past weekend, urging them to vote “no” in a bid to retain their seats and preserve the KMT’s majority in the Legislative Yuan. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which had largely kept its distance from the civic recall campaigns, earlier this month instructed its officials and staff to support the recall groups in a final push to protect the nation. The justification for the recalls has increasingly been framed as a “resistance” movement against China and

Jaw Shaw-kong (趙少康), former chairman of Broadcasting Corp of China and leader of the “blue fighters,” recently announced that he had canned his trip to east Africa, and he would stay in Taiwan for the recall vote on Saturday. He added that he hoped “his friends in the blue camp would follow his lead.” His statement is quite interesting for a few reasons. Jaw had been criticized following media reports that he would be traveling in east Africa during the recall vote. While he decided to stay in Taiwan after drawing a lot of flak, his hesitation says it all: If

Saturday is the day of the first batch of recall votes primarily targeting lawmakers of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). The scale of the recall drive far outstrips the expectations from when the idea was mooted in January by Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) caucus whip Ker Chien-ming (柯建銘). The mass recall effort is reminiscent of the Sunflower movement protests against the then-KMT government’s non-transparent attempts to push through a controversial cross-strait service trade agreement in 2014. That movement, initiated by students, civic groups and non-governmental organizations, included student-led protesters occupying the main legislative chamber for three weeks. The two movements are linked