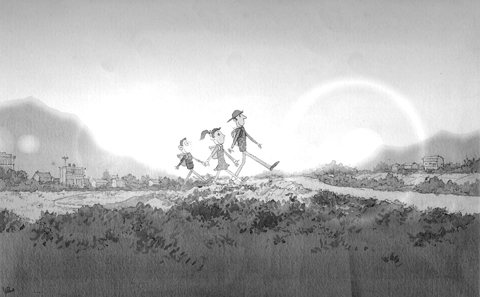

To get to school, the child leaves home by herself, proudly walking down the boulevard in a suburb of a small city in upstate New York. The crossing guard helps her at the intersection. She lives only a block and a half from school. Yet she walks by older children waiting with parents for buses to the same school.

She is seven, a second-grader, and her mother, Katie, hears the raised-eyebrow remarks.

“Are you sure you want to be doing this?” Katie said friends ask.

A stay-at-home mother, she asked that her identity be shielded to protect her children.

“‘She’s just so pretty. She’s just so ... blond.’ A friend said, ‘I heard that Jaycee Dugard story, and I thought of your daughter.’ And they say, ‘I’d never do that with my kid: I wouldn’t trust my kid with the street.’”

Katie, too, is tormented by the abduction monsters embedded in modern parenting. Yet she wants to encourage her daughter’s independence.

“Somehow, walking to school has become a political act when it’s this uncommon,” she said. “Somebody has to be first.”

It has been 30 years since the May morning when Julie Patz, a Manhattan mother, finally allowed her six-year-old son, Etan, to walk by himself to the school bus stop, two blocks away. She watched till he crossed the street — and never saw him again.

Since that haunting case, a generation of parents and administrators has created dense rituals of supervision around what used to be a mere afterthought of childhood: taking yourself to and from school.

Certain realities also shape these procedures, like the schedules of working parents, unsafe neighborhoods and school transportation cuts.

But when these constraints are mixed with anxiety over transferring children from the private world of family to the public world of school, the new normal can look increasingly baroque.

Now, in some suburbs, parents and children sit in their cars at the end of driveways, waiting for the bus. Children are driven to schools two blocks away. At some schools, parents drive up with their children’s names displayed on their dashboards, a school official radios to the building, and each child is escorted out.

When to detach the parental leash? The trip to and from school has become emblematic of the conflict parents feel between teaching children autonomy and keeping them safe. In parenting blogs and books, the school bus stop itself is shorthand for the turmoil of contemporary parents over when to relinquish control.

Parents’ worst nightmares were inflamed recently by the re-emergence of Jaycee Dugard, the 11-year-old girl who was kidnapped on her way to the school bus 18 years ago in northern California.

The fear of abduction by strangers “has become a norm within middle-class parental circles,” said Paula Fass, a history professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of Kidnapped: Child Abduction in America. “We try to control our fears to the nth degree, so we drop our children off right at school. It’s a confirmation that ‘I’m a good parent.’”

In 1969, 41 percent of children either walked or biked to school; by 2001, only 13 percent still did, according to data from the National Household Travel Survey. In many low-income neighborhoods, children have no choice but to walk. During the same period, children either being driven or driving themselves to school rose to 55 percent from 20 percent. Experts say the transition has not only contributed to the rise in pollution, traffic congestion and childhood obesity, but has also hampered children’s ability to navigate the world.

In a study of San Francisco Bay Area parents who drove children ages 10 to 14 to school, published this summer in the Journal of the American Planning Association, half would not allow them to walk without supervision, and 30 percent said fear of strangers governed their decision.

In recent years, parents like Katie have begun to push back. They often encounter disapproval by other parents, scoldings by school administrators and even visits from local constabularies.

“I don’t feel you can be a parent and not feel nervous,” said Lenore Skenazy, whose recent book, Free-Range Kids: Giving Our Children the Freedom We Had Without Going Nuts with Worry, looks at parental fears and statistical realities. “But we don’t do them a service by going to the worst-case scenario in your mind and acting accordingly. Organizing your life around the images of Etan Patz and Jaycee Dugard negates the joy you had walking to school as a kid or even the sense that you could take care of yourself.”

Denise Schipani, a writer in Huntington Station, New York, recently added a post on her blog, Confessions of a Mean Mommy, entitled “The Bus Stop Conundrum.” Schipani herself grew up in an era when “we had a life outside the house that had nothing to do with our parents,” she said.

“Kids used to do more things on their own because they could. No one was saying, ‘not until you’re 10 or 12.’ But on our street, people drive fast and my kids expect me to wait with them for the school bus,” she said.

So do other mothers. “How long do I have to do this? What are the rules?” she asked.

The federally funded Safe Routes to School program has been working with communities to address problems that impede children from walking or biking to school. Particularly since last summer, when gas prices rose and districts began cutting budgets, some districts have been turning to the “walking school bus,” in which parent volunteers walk groups of children to school.

But communal will around this issue has not arrived in many places. In Columbus, Mississippi, Lori Pierce would like her daughters, six and eight, to walk the mile to school by the end of the year.

“They want to walk,” she said. “They have scooters.”

But she and the girls face obstacles. Pierce must teach them the rules of a busy street, get officials to install some sidewalks and urge the school to hire a crossing guard.

And Pierce faces another obstacle to becoming a free-range mother: public opinion.

Last spring, her son, 10, announced he wanted to walk to soccer practice rather than be driven, a distance of about a mile. Several people who saw the boy walking alone called 911.

A police officer stopped him, drove him the rest of the way and then reprimanded Pierce. According to local news reports, the officer told Pierce that if anything untoward had happened to the boy, she could have been charged with child endangerment. Many felt the officer acted appropriately and that Pierce had put her child at risk.

Critics say fears that children will be abducted by strangers are at a panic level unjustified by reality. About 100 children were kidnapped by strangers in 1999, according to federal crime statistics. Skenazy writes that children are 40 times more likely to die in a car trip than walking to school.

But Skenazy, who prompted an uproar last year when she wrote a column about allowing her nine-year-old son to take a New York City subway and bus alone, said that the alarm parents feel has been stoked by sensation-seeking news outlets and crime shows like Law & Order: Special Victims Unit.

“On TV, most criminals are strangers,” she said. “That sinks into your view of the world and you think all strangers are to be distrusted.”

Schools are skittish about unsupervised young walkers. Even though Lisa Reid, who lives in a suburb of Vancouver in Canada, had signed a permission form, when her first-grader proudly told his teacher he was walking home himself last spring, a distance of six houses, the teacher was incredulous. She took him to the office and called Reid, who didn’t hear the phone.

That was because Reid was pacing at the end of the driveway, waiting for her son, her worries climbing exponentially as the moments ticked by.

Reid used to teach in a Vancouver school where many students were refugees.

“Those kids all walked home,” she said. “They came from countries where they walked through terrible, horrible things and they thought it was great to be safe here on our streets.”

Jonathan Zimmerman, a professor at New York University who writes about the history of American education, said that schools themselves should not be blamed for what some might consider hyper-vigilance.

“The public school is the most grassroots institution we have,” he said. “They’re responding to very real demands. This is clearly something that has engaged and agitated the public.”

Not only institutions feel threatened when individuals wander off the range — so do other parents.

Recently, Amy Utzinger, a mother of four in Tucson, Arizona, let her daughter, age seven, walk down the block to play with a friend. Five houses. Same side of the street.

Afterward, the friend’s mother drove Utzinger’s daughter home.

“She said, ‘I just drove her back, just in case ... you know,’” recalled Utzinger. “What was I supposed to say? How can you argue against ‘just in case’?”

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion