Floating, cocktail drink in hand, in the pool of a five-star hotel in Cuba, Alexis basks in a holiday experience that for years was out of reach for him in his own homeland.

The pastel-colored hotel buildings, the well-ordered gardens, the turquoise waters and the perpetually smiling waiters — all just 140km east of his home in Havana. So near, and yet for many years, so far away.

Until last year, Cuba’s communist government prevented its citizens from entering hotels reserved for hard currency-paying foreign tourists. It argued that tourism was a strategic revenue sector and that widening access would create inequalities in a socialist society, where most earn inconvertible Cuban pesos.

The tourist hotels, whose services, shops and restaurants are a world away from the hardships and shortages experienced by most Cubans, remained largely out of bounds for ordinary citizens. This prohibition angered most Cubans, who considered it made them second-class citizens in their own homeland.

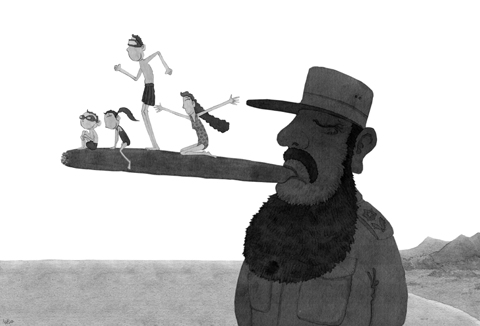

But when Cuban President Raul Castro took over from his ailing older brother Fidel Castro last year, one of his first acts was to end the ban and open all facilities to Cubans. The change was widely popular even though most islanders still cannot afford to stay at the tourist hotels.

“Let me tell you, this is great,” said Alexis, an employee of a state-run Havana hard currency store who declined to give his full name, as his girlfriend returned from the bar with more “mojito” cocktails — a tropical mix of lime juice, Cuban rum, and mint leaves.

In the years immediately following the 1959 revolution, Cuban workers were allowed into the island’s premier resorts, yet the need to earn much-needed hard currency led to the development again of a more exclusive foreign tourism sector, especially over the last 15 years.

But the global financial crisis has taken a big bite out of Cuba’s international tourism, so the Cuban travel industry, seeking to boost occupation in half-empty hotels, has begun offering reduced-price package deals to Cubans.

At US$70 a night for an all-inclusive hotel in Varadero, Cuba’s premier beach resort, prices are well below what foreigners pay, but still out of reach for most Cubans struggling to make ends meet on state salaries that average less than US$20 a month.

Tourism Minister Manuel Marrero said Cubans have accounted for 10 percent of occupancy at Cuba’s high-end hotels this summer.

THE SWEET LIFE

The opening of a domestic market is giving more visibility to an emerging class of wealthier Cubans who have hard currency in their pockets and are eager to sport the colored wristbands of the fancy all-inclusive hotels.

The new Cuban internal tourists are professionals, technicians working for foreign joint ventures and people receiving dollar remittances from relatives living abroad.

“Before a foreigner would ask us about Varadero and we did not know what to say,” recalls Roberto Garcia, a 43-year-old engineer who arrived from Havana with his family of six. “Now, if you have the money, you can do it.”

Without precise official figures on revenue from internal Cuban tourism, it is difficult to gauge just how much of a boost this new access is giving to the cash-strapped economy.

But to the extent that Cuban tourist spending increases the flow of dollars to the island — by, for example, family members in Miami financing a trip to Varadero for their Cuban relatives — it is helpful, Cuba expert Paolo Spadoni said.

“Financing from abroad might also play quite an important role,” said Spadoni, a post-doctoral fellow at Tulane University’s Center for Inter-American Policy and Research.

Some Cubans interviewed on a recent trip to Varadero said expenses were paid by relatives visiting from the US, a flow that is up 20 percent since US President Barack Obama lifted travel restrictions in April on Cuban-Americans visiting the island.

But Obama has made clear he will keep a 47-year-old US trade embargo on Cuba in place for the moment to press Cuban leaders to improve human rights and political freedoms. Havana, while agreeing to talks on migration and other issues, has said it will not make “concessions” for improved ties.

FOR THE PEOPLE

With the help of foreign investors, Cuba reluctantly developed its tourism industry in the mid-1990s in response to the deep economic crisis that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union, its chief benefactor and ally for decades.

“All the money made here is for the people,” proclaims a banner at the entrance to Varadero, a 20km peninsula of white-sand beaches lined with big hotels.

This slogan reflects the long-used government argument that tourism revenues are employed to benefit all of Cuba’s people by helping to pay for free health care and education.

Cuba has some 55,000 hotel rooms managed by the state, many in association with foreign hotel heavyweights such as Sol Melia of Spain, the French firm Accor or Jamaica’s Sandals Resorts.

Attracted by the country’s beaches and enduring revolutionary mystique, 2.3 million foreign tourists, mostly from Canada and in Europe, visited Cuba last year, which brought the island US$2.5 billion in revenues and made tourism one of Cuba’s main sources of hard currency.

Raul Castro said in a speech earlier this month that the number of international tourists is up, but revenues are down compared to last year.

Both numbers are expected to grow if the US Congress approves a proposed bill that would allow all Americans to freely visit Cuba, currently prohibited by the US embargo against the island 145km from Key West, Florida.

But for now, Cuba is looking to Cubans to keep its hotels humming, and people like Alexis are happy to help.

“This is just fantasy. Real life starts again on Monday when we get back to Havana,” he said between sips of a last mojito as the sun set over Varadero.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

In her article in Foreign Affairs, “A Perfect Storm for Taiwan in 2026?,” Yun Sun (孫韻), director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said that the US has grown indifferent to Taiwan, contending that, since it has long been the fear of US intervention — and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) inability to prevail against US forces — that has deterred China from using force against Taiwan, this perceived indifference from the US could lead China to conclude that a window of opportunity for a Taiwan invasion has opened this year. Most notably, she observes that

For Taiwan, the ongoing US and Israeli strikes on Iranian targets are a warning signal: When a major power stretches the boundaries of self-defense, smaller states feel the tremors first. Taiwan’s security rests on two pillars: US deterrence and the credibility of international law. The first deters coercion from China. The second legitimizes Taiwan’s place in the international community. One is material. The other is moral. Both are indispensable. Under the UN Charter, force is lawful only in response to an armed attack or with UN Security Council authorization. Even pre-emptive self-defense — long debated — requires a demonstrably imminent

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) said on Monday that it would be announcing its mayoral nominees for New Taipei City, Yilan County and Chiayi City on March 11, after which it would begin talks with the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) to field joint opposition candidates. The KMT would likely support Deputy Taipei Mayor Lee Shu-chuan (李四川) as its candidate for New Taipei City. The TPP is fielding its chairman, Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌), for New Taipei City mayor, after Huang had officially announced his candidacy in December last year. Speaking in a radio program, Huang was asked whether he would join Lee’s