When Tokyo prosecutors arrested an aide to a prominent opposition political leader in March, they touched off a damaging scandal just as the entrenched Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) seemed to face defeat in coming elections.

Many Japanese cried foul, but you would not know that from the coverage by Japan’s big newspapers and TV networks.

Instead, they mostly reported at face value a stream of anonymous allegations, some of them thinly veiled leaks from within the investigation, of illegal campaign donations from a construction company to the opposition leader, Ichiro Ozawa.

This month, after weeks of such negative publicity, Ozawa resigned as head of the opposition Democratic Party.

The resignation, too, provoked a rare outpouring of criticism aimed at the powerful prosecutors by Japanese across the political spectrum, and even from some former prosecutors, who seldom criticize their own in public. The complaints range from accusations of political meddling to concerns that the prosecutors may have simply been insensitive to the arrest’s timing.

But just as alarming, say academic and former prosecutors, has been the failure of the news media to press the prosecutors for answers, particularly at a crucial moment in Japan’s democracy, when the nation may be on the verge of replacing a half-century of LDP rule with more competitive two-party politics.

“The mass media are failing to tell the people what is at stake,” said Terumasa Nakanishi, a conservative academic who teaches international politics at Kyoto University. “Japan could be about to lose its best chance to change governments and break its political paralysis, and the people don’t even know it.”

The arrest of the aide seemed to confirm fears among voters that Ozawa, a veteran political boss, was no cleaner than the Liberal Democrats he was seeking to replace. It also seemed to at least temporarily derail the opposition Democrats ahead of the elections, which must be called by early September. The party’s lead in opinion polls was eroded, though its ratings rebounded slightly after the selection this month of a new leader, Yukio Hatoyama, a Stanford-educated engineer.

Japanese journalists acknowledge that their coverage so far has been harsh on Ozawa and generally positive toward the investigation, though newspapers have run opinion pieces criticizing the prosecutors. But they bridle at the suggestion that they are just following the prosecutors’ lead, or just repeating information leaked to them.

“The Asahi Shimbun has never run an article based solely on a leak from prosecutors,” the newspaper, one of Japan’s biggest dailies, said in a written reply to questions from the New York Times.

Still, journalists admit that their coverage could raise questions about the Japanese news media’s independence, and not for the first time. Big news organizations here have long been accused of being too cozy with centers of power.

Indeed, academics say coverage of the Ozawa affair echoes the positive coverage given to earlier arrests of others who dared to challenge the establishment, like the iconoclastic Internet entrepreneur Takafumi Horie.

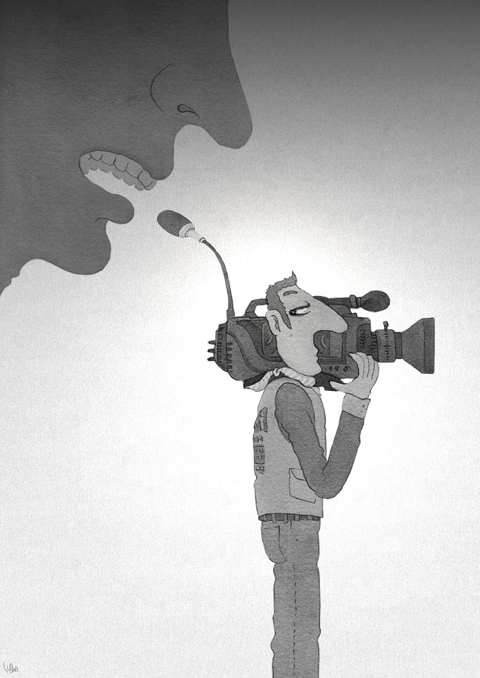

“The news media should be watchdogs on authority,” said Yasuhiko Tajima, a journalism professor at Sophia University in Tokyo, “but they act more like authority’s guard dogs.”

While news media in the US and elsewhere face similar criticisms of being too close to government, the problem is more entrenched here. Cozy ties with government agencies are institutionalized in Japan’s so-called press clubs, cartel-like arrangements that give exclusive access to members, usually large domestic news outlets.

Critics have long said this system leads to bland reporting that adheres to the official line. Journalists say they maintain their independence despite the press clubs. But they also say government officials sometimes try to force them to toe the line with threats of losing access to information.

Last month, the Tokyo Shimbun, a smaller daily known for coverage that is often feistier than that in Japan’s large national newspapers, was barred from talking with Tokyo prosecutors for three weeks after printing an investigative story about a governing-party lawmaker who had received donations from the same company linked to Ozawa.

The newspaper said it was punished simply for reporting something the prosecutors did not want made public.

“Crossing the prosecutors is one of the last media taboos,” said Haruyoshi Seguchi, the paper’s chief reporter in the Tokyo prosecutors’ press club.

The news media’s failure to act as a check has allowed prosecutors to act freely without explaining themselves to the public, said Nobuto Hosaka, a member of parliament for the opposition Social Democratic Party, who has written extensively about the investigation on his blog.

He said he believed Ozawa was singled out because of the Democratic Party’s campaign pledges to curtail Japan’s powerful bureaucrats, including the prosecutors. (The Tokyo prosecutors office turned down an interview request for this story because the Times is not in its press club.)

Japanese journalists defended their focus on Ozawa’s alleged misdeeds, arguing that the public needed to know about a man who at the time was likely to become the next prime minister. They also say they have written more about Ozawa because of a pack-like charge among reporters to get scoops on those who are the focus of an investigation.

“There’s a competitive rush to write as much as we can about a scandal,” said Takashi Ichida, who covers the Tokyo prosecutors office for the Asahi Shimbun.

But that does not explain why in this case so few Japanese reporters delved deeply into allegations that the company also sent money to LDP lawmakers.

The answer, as most Japanese reporters will acknowledge, is that following the prosecutors’ lead was easier than risking their wrath by doing original reporting.

The news media can seem so unrelentingly supportive in their reporting on investigations like that into Ozawa that even some former prosecutors, who once benefited from such favorable coverage, have begun criticizing them.

“It felt great when I was a prosecutor,” said Norio Munakata, a retired, 36-year veteran Tokyo prosecutor. “But now as a private citizen, I have to say that I feel cheated.”

There is a modern roadway stretching from central Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, to the partially recognized state’s Egal International Airport. Emblazoned on a gold plaque marking the road’s inauguration in July last year, just below the flags of Somaliland and the Republic of China (ROC), is the road’s official name: “Taiwan Avenue.” The first phase of construction of the upgraded road, with new sidewalks and a modern drainage system to reduce flooding, was 70 percent funded by Taipei, which contributed US$1.85 million. That is a relatively modest sum for the effect on international perception, and

At the end of last year, a diplomatic development with consequences reaching well beyond the regional level emerged. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared Israel’s recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state, paving the way for political, economic and strategic cooperation with the African nation. The diplomatic breakthrough yields, above all, substantial and tangible benefits for the two countries, enhancing Somaliland’s international posture, with a state prepared to champion its bid for broader legitimacy. With Israel’s support, Somaliland might also benefit from the expertise of Israeli companies in fields such as mineral exploration and water management, as underscored by Israeli Minister of

When former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) first took office in 2016, she set ambitious goals for remaking the energy mix in Taiwan. At the core of this effort was a significant expansion of the percentage of renewable energy generated to keep pace with growing domestic and global demands to reduce emissions. This effort met with broad bipartisan support as all three major parties placed expanding renewable energy at the center of their energy platforms. However, over the past several years partisanship has become a major headwind in realizing a set of energy goals that all three parties profess to want. Tsai

On Sunday, elite free solo climber Alex Honnold — famous worldwide for scaling sheer rock faces without ropes — climbed Taipei 101, once the world’s tallest building and still the most recognizable symbol of Taiwan’s modern identity. Widespread media coverage not only promoted Taiwan, but also saw the Republic of China (ROC) flag fluttering beside the building, breaking through China’s political constraints on Taiwan. That visual impact did not happen by accident. Credit belongs to Taipei 101 chairwoman Janet Chia (賈永婕), who reportedly took the extra step of replacing surrounding flags with the ROC flag ahead of the climb. Just