After starting the day with prayers and songs in honor of the Prophet Mohammed's birthday, the students at the Madrasah al-Irsyad al-Islamiah in Singapore turned to the secular. An all-girls chemistry class grappled with compounds and acids, while other students focused on English, math and other subjects from the national curriculum.

Teachers exhorted their students to ask questions. Some, true to the school's embrace of new technology, gauged their students' comprehension with individual polling devices.

“It's like American Idol,“ said Razak Mohamed Lazim, the head of al-Irsyad, which means “rightly guided.”

A reference to the reality TV program in relation to an Islamic school may come as a surprise. But Singapore's Muslim leaders see al-Irsyad, with its strict balance between religious and secular studies, as the future of Islamic education, not only in Singapore but elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

Two madrasah in Indonesia have adopted al-Irsyad's curriculum and management, attracted to what they say is a progressive model of Islamic education in tune with the modern world. For them, al-Irsyad is the counterpoint to many traditional madrasah that emphasize religious studies at the expense of everything else. Instead of preaching radicalism, the school's in-house textbooks praise globalization and international organizations like the UN.

Leaders in Islamic education here rue the fact that, in much of the West, madrasah everywhere have been broad-brushed as militant hotbeds where students spend days learning the Koran by heart. Still, they were relieved that no terrorism suspect in the region in recent years was a product of Singapore's madrasah, though some suspects were linked to madrasah in Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries. That association deepened a long-running debate over the nature of Islamic education.

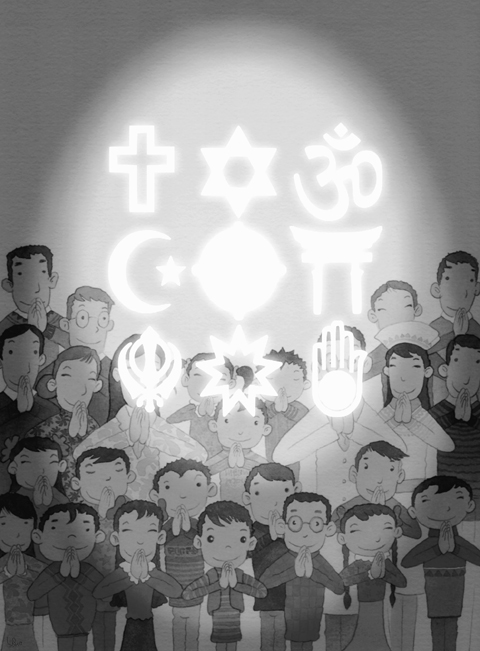

“The Muslim world in general is struggling with its Islamic education,” Razak said, adding that Islamic schools had failed to adapt to the modern world. “In many cases, it's also the challenge the Muslim world is facing. We are not addressing the needs of Islam as a faith that has to be alive, interacting with other communities and other religions.”

In Indonesia, most Islamic schools still pay little attention to secular subjects, believing that religious studies are enough, said Indri Rini Andriani, a former computer programmer who is the principal of al-Irsyad Satya Islamic School, one of the Indonesian schools that model themselves on the school here.

“They feel that conventional education is best for the children, while some of us feel that we have to adjust with advances in technology and what’s going on in the world,” Indri said.

Here, the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore, a statutory board that advises the government on Muslim affairs, gave al-Irsyad a central spot in its new Islamic center. Long the top academic performer among the country’s six madrasah, al-Irsyad was chosen to be in the center as “a showcase,” said Razak, who is also an official at the religious council.

The school's 900 primary and secondary-level students follow the national curriculum of the country's public schools while also taking religious instruction. To accommodate both, the school day is three hours longer than at the mainstream schools.

Mohamed Muneer, 32, a chemistry teacher, said most of his former students had gone on to junior colleges or polytechnic schools, while some top students attended the National University of Singapore.

“Many became administrators, some are teaching and some joined the civil service,” he said.

At the cafeteria, Ishak bin Johari, a 17-year-old who wants to become a newspaper reporter, said the balance between the secular and religious would help the school's graduates “lead normal Singaporean lives compared to other madrasah students.”

That balance resulted, like many things in this country, from pressure by the government. Singapore's madrasah — historically the schools for ethnic Malays who make up about 14 percent of the country’s population — experienced a surge in popularity in the 1990s along with a renewed interest in Islam.

But that surge, coupled with the madrasah's poor record in nonreligious subjects, high dropout rates and graduation of young people with few marketable job skills, worried the government. It responded by making primary education at public schools compulsory in 2003, allowing exceptions like the madrasah, provided they met basic standards by next year. If they fail, they will have to stop educating primary schoolchildren.

Last year, the first time all six madrasah were required to sit for national exams at the primary level, two failed to meet minimal standards, though they still had two more years to pass.

Al-Irsyad, which was the first to alter its curriculum, outperformed the other madrasah. But neither it nor the others made any of the lists of best performing schools or students compiled by the Education Ministry in Singapore.

Mukhlis Abu Bakar, an expert on madrasah at the National Institute of Education who also was a member of al-Irsyad’s management committee in the 1990s, said the madrasah still had a long way to go to catch up with mainstream schools. While Singapore's teachers are among the most highly paid civil servants, the madrasah have had trouble attracting teachers because they rely only on tuition and donations, he said.

“I think al-Irsyad has not achieved a level where I would say it is a model for Islamic education, but ... the system it has in place could become one,” he said.

Still, it began to draw students who would not have attended a madrasah otherwise. Noridah Mahad, 44, said she had wanted to send her two older children to madrasah but worried over the quality of education. With al-Irsyad's adoption of the national curriculum, she felt no qualms in sending her third child.

“Here they teach many things other than Islam,” she said.

Al-Irsyad said it was in talks to export its model to madrasah in the Philippines and Thailand. In Indonesia, Dahlan Iskan, the chairman of Jawa Pos Group, one of the country's biggest media companies, opened a school modeled on Singapore's. And a conglomerate, the Lyman Group, backed al-Irsyad Satya.

Poedji Koentarso, a retired diplomat, led the search for Lyman, visiting madrasah all over Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.

“We shopped around,” he said. “It was a difficult search in the sense that often the schools were very religious, too religious.”

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

For Taiwan, the ongoing US and Israeli strikes on Iranian targets are a warning signal: When a major power stretches the boundaries of self-defense, smaller states feel the tremors first. Taiwan’s security rests on two pillars: US deterrence and the credibility of international law. The first deters coercion from China. The second legitimizes Taiwan’s place in the international community. One is material. The other is moral. Both are indispensable. Under the UN Charter, force is lawful only in response to an armed attack or with UN Security Council authorization. Even pre-emptive self-defense — long debated — requires a demonstrably imminent

Since being re-elected, US President Donald Trump has consistently taken concrete action to counter China and to safeguard the interests of the US and other democratic nations. The attacks on Iran, the earlier capture of deposed of Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro and efforts to remove Chinese influence from the Panama Canal all demonstrate that, as tensions with Beijing intensify, Washington has adopted a hardline stance aimed at weakening its power. Iran and Venezuela are important allies and major oil suppliers of China, and the US has effectively decapitated both. The US has continuously strengthened its military presence in the Philippines. Japanese Prime

After “Operation Absolute Resolve” to capture former Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro, the US joined Israel on Saturday last week in launching “Operation Epic Fury” to remove Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his theocratic regime leadership team. The two blitzes are widely believed to be a prelude to US President Donald Trump changing the geopolitical landscape in the Indo-Pacific region, targeting China’s rise. In the National Security Strategic report released in December last year, the Trump administration made it clear that the US would focus on “restoring American pre-eminence in the Western hemisphere,” and “competing with China economically and militarily