This village of straw huts sits on a sea of sand 100km from the nearest paved road. Camels and girls with jerrycans crowd around the watering holes. There’s little electricity and not a single TV.

However, on the edge of Dertu stands a shimmering sign of progress — a new cellphone tower. And that means farmers no longer have to travel for hours to learn the latest market prices; they can get them by text message.

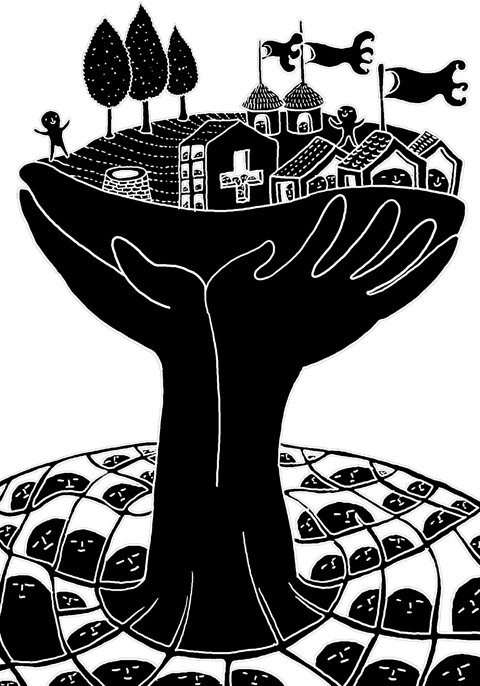

It’s one of many innovations that have come to these 6,000 people in eastern Kenya and to 13 other such villages scattered around 10 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. They are called Millennium Villages, designed to show how aid and smart, simple technology can advance the UN’s Millennium Development Goals of dramatically reducing global poverty and boosting education, gender equality and health by 2015.

The UN is hosting a summit in New York this week to review progress since the goals were set 10 years ago.

About 70 percent of Dertu’s people earn less than US$1 a day and most depend on food aid. The two-room hotel charges US$1.25 a night.

Generators and solar energy provide some basic needs, like charging cell phones, but the school’s nine donated computers aren’t yet connected to the Internet.

Not surprisingly, the advent of Millennium Village status four years ago generated exaggerated expectations and now some villagers feel disappointed. There is also sharp debate between supporters and detractors about whether the idea can be “scaled up” into sweeping solutions for the world’s poorest region.

Yet improvements can be seen in Dertu: four new health care workers, free medicines and vaccines, a birthing center and laboratory under construction, bed nets to ward of mosquitoes. In 2006, 49 percent of 916 individuals tested had malaria. That rate has dropped to 8 percent.

School attendance has doubled for boys and tripled for girls, there are high school scholarships and a dorm for boys. Each village gets US$120 in spending per person per year, half from the villages project, the rest from the government or aid groups.

As a result, Dertu, which barely existed until UNICEF dug a well here 13 years ago, has become a magnet for surrounding villages.

“A lot has to be done still to meet the Millennium Development Goals. A lot has been done and for that we are thankful,” said Ibrahim Ali Hassan, a 60-year-old village elder with dyed red hair, who waves a cellphone in his hand as he talks.

Of the complainers, he remarks: “They think now that we are a Millennium Village they will be built a house with an ocean view.”

Mohamed Ahmed Abdi, 58, heads the Millennium Village Committee, liaison between the project and the villagers. He gripes that there are too few teachers and that the well water is salty and unhealthy.

“There is a difference between what we have been told and what really exists. We have been told that ‘Your village is the Millennium Village.’ We have been told that ‘You will get roads, electricity, water and education,’” he said.

The Millennium Villages are the brainchild of Jeffrey Sachs, the Columbia University economist who is special adviser to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on the Millennium Development Goals.

Sachs readily acknowledges that Dertu hasn’t made a breakthrough, calling it “one of the most difficult venues on the whole planet.”

However, he points to other advances in lifting villages out of extreme poverty.

“I think on the whole they’ve been a tremendous success, not only in what they are accomplishing on the ground, but also opening eyes to what can be accomplished more generally,” Sachs said. “They’re a proving ground of how to create effective systems in health, education, local infrastructure, business development and agriculture.”

The project’s report for this year says bed net use by children under 5 has risen from 7 percent to 50 percent across the 14 villages. Malaria rates have dropped from 24 percent to 10 percent.

Maize yields are up, chronic malnutrition is down, more babies are delivered by health professionals.

Among the critics is Nicolas van de Walle, a fellow at the Center for Global Development and a professor at Cornell University.

He says he admires Sachs for putting development on the agenda, “But, no, in general I think these villages are largely a gimmick and a substantial waste of money.”

“The idea that if you spend a lot of money on poor villagers in Kenya, their lives will improve, is not seriously in doubt. The real issue is how to do this at a national level, in a sustainable way that builds individual and institutional capacity, empowers citizens and their democratically elected governments. It seems to me that in that sense the villagers have failed,” van de Walle said.

However, Sachs singles out Nigeria as a nation that is taking his idea to the next level.

He said sub-Saharan Africa’s most populous country is launching a major initiative next year, largely based on the Millennium Villages, that will reach 20 million people.

Dertu’s ripple effect is felt 5km away, in a temporary community of 250 nomads, where children were learning the alphabet under a tree fenced in by thorn bushes that keeps the lions away at night.

Eleven-year-old Ibrahim pointed at the chalkboard as 12 barefoot children recited “A is for apple, B is for boy.”

It was Sachs who hired them a teacher — 28-year-old Abdullahi Bari. He lives in a backpacker’s tent, and when the nomads leave their straw huts to lead their camels, cattle, goats and sheep to greener pastures, Bari will go too.

“Whenever they move I move with them. I have my own camel,” he said.

Bari faces a host of difficulties. None of the parents can read. Their kids herd animals and miss class. His oldest first-year student is 21. He hopes to teach the kids for three years and send them to a boarding school in Dertu.

“It’s hot during the day and there’s not enough water. The water point is far away,” Bari said. “It is a big challenge ... but we will try our best.”

Mohammed Qumane Omar, the community’s chief, a turbaned man with deep gray eyes, said he wants his children to have a better life than his.

“I’m illiterate. I move around from place to place. The reason I settled here is so they can be closer to schools. I want them to be doctors, teachers or even more than that.”

One problem mentioned by Hassan, the tribal elder, is corruption, which critics of international aid often point to.

The acting coordinator in Dertu, Patrick Mutuo, says his predecessor didn’t follow procedures and visited the village rarely.

As a result, the coordinator’s contract wasn’t renewed earlier this year.

“With these weak procedures it is likely that money was lost,” Mutuo said, adding that he had no figure.

A statement from the Millennium Village (MV) project said: “We were not satisfied that all procedures were being well followed ... In all MV sites, efficiency and transparency are core standards and management practices. We aim for continuous improvement in practice.”

Still, Hassan says he gives “special thanks” to Sachs, while Sofia Ali Guhad, the head teacher at the Dertu school, spoke of the problem of exaggerated expectations and the pitfalls of success.

Because school enrollment is up, she needs more classrooms, desks and dorm space and living quarters.

“The expectation was very high for the community, but we have received very little,” Guhad said, but later added: “Life is good. In fact it has improved. They are assisting us as much as they can.”

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its