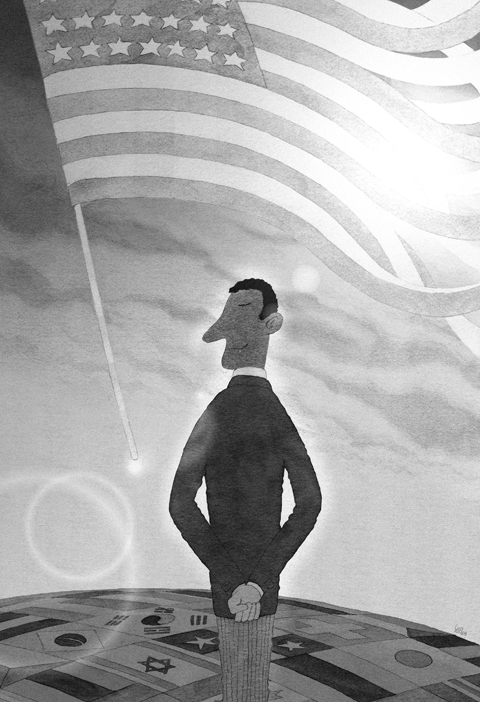

One of the first challenges that US president-elect Barack Obama will face is the effect of the ongoing financial crisis, which has called into question the future of US power. An article in the Far Eastern Economic Review proclaims that “Wall Street’s crack-up presages a global tectonic shift: the beginning of the decline of American power.” Russian President Dmitri Medvedev sees the crisis as a sign that the US’ global leadership is coming to an end, and Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez has declared that Beijing is now much more relevant than New York.

Yet the dollar, a symbol of US financial power, has surged rather than declined. As Kenneth Rogoff, a Harvard professor and former chief economist of the IMF notes, “It is ironic, given that we just messed up big-time, that the response of foreigners is to pour more money into us. They’re not sure where else to go. They seem to have more confidence in our ability to solve our problems than we do.”

It used to be said that when the US sneezed, the rest of the world caught a cold. More recently, many claimed that with the rise of China and the petro-states, a US slowdown could be decoupled from the rest of the world. But when the US caught the financial flu, others followed. Many foreign leaders quickly switched from schadenfreude to fear — and to the security of US Treasury bills.

Crises often refute conventional wisdom, and this one reveals that the underlying strength of the US economy remains impressive. The poor performance of Wall Street and US regulators has cost the US a good deal in terms of the soft power of its economic model’s attractiveness, but the blow need not be fatal if, in contrast to Japan in the 1990s, the US manages to absorb the losses and limit the damage. The World Economic Forum still rates the US economy as the world’s most competitive, owing to its labor-market flexibility, higher education, political stability and openness to innovation.

The larger question concerns the long-term future of US power. A new forecast for 2025 being prepared by the US National Intelligence Council projects that US dominance will be “much diminished,” and that the one key area of continued American superiority — military power — will be less significant in the competitive world of the future. This is not so much a question of US decline as “the rise of the rest.”

Power always depends on context, and in today’s world, it is distributed in a pattern that resembles a complex three-dimensional chess game. On the top chessboard, military power is largely unipolar and likely to remain so for a while. But on the middle chessboard, economic power is already multi-polar, with the US, Europe, Japan and China as the major players, and others gaining in importance.

The bottom chessboard is the realm of transnational relations that cross borders outside of government control. It includes actors as diverse as bankers electronically transferring sums larger than most national budgets, as well as terrorists transferring weapons or hackers disrupting Internet operations. It also includes new challenges like pandemics and climate change. On this bottom board, power is widely dispersed, and it makes no sense to speak of unipolarity, multipolarity or hegemony.

Even in the aftermath of the financial crisis, the giddy pace of technological change is likely to continue to drive globalization, but the political effects will be different for the world of nation-states and the world of non-state actors. In inter-state politics, the most important factor will be the continuing “return of Asia.”

In 1750, Asia had three-fifths of the world population and three-fifths of the world’s economic output. By 1900, after the industrial revolution in Europe and America, Asia accounted for just one-fifth of world output. By 2040, Asia will be well on its way back to its historical share.

The rise of China and India may create instability, but it is a problem with precedents, and we can learn from history about how policies can affect the outcome. A century ago, Britain managed the rise of US power without conflict, but the world’s failure to manage the rise of German power led to two devastating world wars.

The rise of non-state actors also must be managed. In 2001, a non-state group killed more Americans than the government of Japan killed at Pearl Harbor. A pandemic spread by birds or travelers on jet aircraft could kill more people than perished in World War I or World War II. The problems of the diffusion of power (away from states) may turn out to be more difficult than shifts in power between states.

The challenge for Obama is that more and more issues and problems are outside the control of even the most powerful state. Although the US does well on the traditional measures of power, those measures increasingly fail to capture much of what defines world politics, which, owing to the information revolution and globalization, is changing in a way that prevents Americans from achieving all their international goals by acting alone.

For example, international financial stability is vital to US prosperity, but the US needs the cooperation of others to ensure it. Global climate change, too, will affect the quality of life, but the US cannot manage the problem alone. And, in a world where borders are becoming increasingly porous to everything from drugs to infectious diseases to terrorism, the US must mobilize international coalitions to address shared threats and challenges.

As the world’s largest economy, US leadership will remain crucial. The problem of American power in the wake of the financial crisis is not one of decline, but of a realization that even the most powerful country cannot achieve its aims without the help of others. Fortunately, Obama understands that.

Joseph Nye, a former US assistant secretary of defense, is a professor at Harvard University.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

George Santayana wrote: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” This article will help readers avoid repeating mistakes by examining four examples from the civil war between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) forces and the Republic of China (ROC) forces that involved two city sieges and two island invasions. The city sieges compared are Changchun (May to October 1948) and Beiping (November 1948 to January 1949, renamed Beijing after its capture), and attempts to invade Kinmen (October 1949) and Hainan (April 1950). Comparing and contrasting these examples, we can learn how Taiwan may prevent a war with

A recent trio of opinion articles in this newspaper reflects the growing anxiety surrounding Washington’s reported request for Taiwan to shift up to 50 percent of its semiconductor production abroad — a process likely to take 10 years, even under the most serious and coordinated effort. Simon H. Tang (湯先鈍) issued a sharp warning (“US trade threatens silicon shield,” Oct. 4, page 8), calling the move a threat to Taiwan’s “silicon shield,” which he argues deters aggression by making Taiwan indispensable. On the same day, Hsiao Hsi-huei (蕭錫惠) (“Responding to US semiconductor policy shift,” Oct. 4, page 8) focused on

Taiwan is rapidly accelerating toward becoming a “super-aged society” — moving at one of the fastest rates globally — with the proportion of elderly people in the population sharply rising. While the demographic shift of “fewer births than deaths” is no longer an anomaly, the nation’s legal framework and social customs appear stuck in the last century. Without adjustments, incidents like last month’s viral kicking incident on the Taipei MRT involving a 73-year-old woman would continue to proliferate, sowing seeds of generational distrust and conflict. The Senior Citizens Welfare Act (老人福利法), originally enacted in 1980 and revised multiple times, positions older

Nvidia Corp’s plan to build its new headquarters at the Beitou Shilin Science Park’s T17 and T18 plots has stalled over a land rights dispute, prompting the Taipei City Government to propose the T12 plot as an alternative. The city government has also increased pressure on Shin Kong Life Insurance Co, which holds the development rights for the T17 and T18 plots. The proposal is the latest by the city government over the past few months — and part of an ongoing negotiation strategy between the two sides. Whether Shin Kong Life Insurance backs down might be the key factor