The advice made her head spin: Have the lump removed. No, let them take the whole breast. Chemotherapy? Radiation? Everyone seemed to have an opinion.

"I just shut everyone down around me," said Bernie Brann, a newly diagnosed cancer patient from upstate New York. "You're just so overwhelmed with information."

Bad advice, or just too much of it, can compound the trauma and damage done by the disease, cancer patients often find. Friends and relatives are important for support, but when these untrained people act as cancer coaches, they can sway people to make poor decisions about their care.

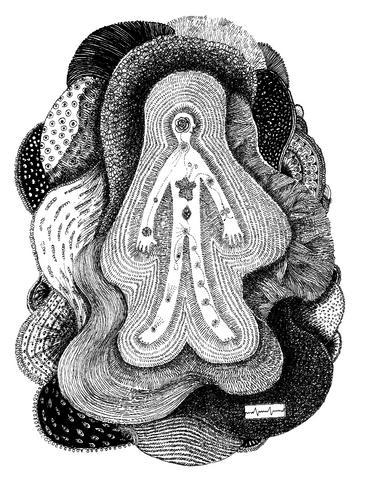

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

This includes survivors, whose opinions are highly valued by patients suddenly facing the scary diagnosis. They may know a lot about cancer, but can do harm if they project their own experiences onto someone else, who may have a different form of the disease that needs different treatment.

Survivors also may be out of touch with changes in the field, where genetic discoveries are rapidly reshaping notions of who needs chemotherapy and what kind.

What is the solution?

Many advocacy groups and hospitals are using "professional" coaches -- trained volunteers or paid workers who can objectively help new patients navigate the maze of information and options.

The American Cancer Society started a patient navigator program a few years ago that now operates in 87 locations and is planning to expand. The National Breast Cancer Coalition also trains coaches, and big treatment hospitals like the University of Texas' M.D. Anderson Cancer Center are increasingly using them for breast, prostate, lung and other types of cancer.

Attendance records were set in December at one of the top training programs, held during the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. More than 240 breast cancer survivors spent late nights at the convention center, taking notes as scientists schooled them on the latest research.

These women go home to volunteer in hospitals and support groups where they staff hotlines, meet with new patients and teach other coaches what they learned. Demand for this training is so great that the Alamo Breast Cancer Foundation gets grants from the Avon Foundation and nine drug companies to subsidize some attendees, but still can't meet the need. Dozens are turned down each year.

To find a coach or navigator, patients can ask their doctors, local cancer hospitals or groups like the cancer society for help. Brann, feeling a need for unbiased help, found a coach by calling the Cancer Resource Center of the Finger Lakes, where associate director Bob Riter provided it.

"People are usually too free about giving advice," said Riter, a survivor of male breast cancer and graduate of the San Antonio program. "We never tell people what to do. We provide information, and we help them think out loud."

Whether amateur or professional, a good cancer coach should offer these things, experts say:

* Support: an ear to listen, a shoulder to cry on, a hand to hold.

* Resources: reliable information or help getting it, and only if the patient wants it.

* Objectivity: a willingness to help patients discover what is best for them, rather than to validate the coach's own cancer battle and choices.

"There's a big difference in saying, `This is what I did' and `Here's what you should do,'" Riter said.

Elderly people are especially vulnerable to having their decisions usurped, he added.

"Sometimes middle-aged kids impose what they want to do on their parents" without asking what the parent wants.

No hard numbers exist on how many cancer patients bring professional coaches or informal ones -- a relative or friend -- to doctor appointments where treatments are discussed.

"The person coming with you can either be an asset or a liability," said Meg Gaines, a lawyer and ovarian cancer survivor who runs the Center for Patient Partnerships, an advocacy resource at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

It is good if the coach can ask questions, gather information and take notes for the shell-shocked patient to use later, she said. It is bad if the coach interferes with the patient's decisions.

Doctors often find themselves in the middle, fighting for the patient's trust. Some choices come down to personal values and risk tolerance, said C. Kent Osborne, a breast cancer specialist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Whether to have chemotherapy is an example. Some women want to avoid it at all cost. Others "don't want to leave any stone unturned," and demand it even if it has harmful side effects and only a 1 percent chance of helping, he said.

As for patients being swayed by others, "a lot of that occurs when they're not in the doctor's office and they go back to their home and their community," Osborne said. "Then well-meaning friends might say, `Well, gee, I was treated with this and you should get that,' or `Aunt Molly got this and you should get that, too,' not understanding that every patient is different."

Patients can fall into the same trap when they coach each other, Gaines said.

"This is the potential downside of support groups -- you don't have expertise around the room," she said. "Someone may be describing her own treatment and others will think, `My doctor didn't tell me that,'" possibly because their cancer is different.

Mary Michaud, policy director at the Wisconsin center, warns: "Beware of people who tell you your experience is going to be just like theirs."

Anna Cluxton, a Columbus, Ohio, woman diagnosed with breast cancer at age 32, feels strongly that she did the right thing having her whole breast removed rather than just the lump. When she coaches other young women whose doctors have advised less drastic surgery, she said she will not express an opinion, but suggests a pointed question: "Ask them, `What will be my chances of recurrence in that same breast?'"

"You need to be aware of all the options" and discuss them fairly, she said.

Vira Brooks, an Omaha public schools administrator, had a different experience 13 years ago. Although she had a tiny, very early-stage tumor, her surgeon recommended removing the whole breast.

She chose less drastic treatment after a survivor she knew coached her through looking at other options.

"She was basically my champion. She helped me navigate the system," Brooks said. "She listened, she shared with me what she had been through," but didn't try to tell her what to do.

Brooks now tries to do the same. She has coached dozens of patients, including black women like herself who are more likely to be diagnosed at later stages and are more likely to die from the disease. A local hospital refers people to her.

As for Bernie Brann, the patient from upstate New York, she did not seek a lot of advice when she was first diagnosed. But word got around at Ithaca College Health Center, where the 69-year-old woman works two nights a week as a nurse's aide.

Doctors told her she could either have a mastectomy or just the lump removed, and at first, she thought she would do the latter.

"But I had so many people saying, `No, no, no, that's not the way to go.' Most people said, `Have a mastectomy.' It was so radical. It just overwhelmed me. It was not something I wanted to do," she said.

She credits her three children with offering support without telling her what to do. Her oldest son went with her to appointments, as did a close friend with nursing training. Ultimately, she changed her mind about what would be best for her, and had a mastectomy in late December.

"I didn't want to go through this again. My feeling was, get in there, get rid of it, get on with your life," she said.

"It's been quite a rollercoaster," she said, but she feels more confident now that she can make good decisions about her future care.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the