Deadly bomb attacks in Bangkok a week ago have rekindled political tensions in Thailand and cast doubt on the ruling junta's promise to restore democracy here after a military coup, analysts say.

The New Year's Eve blasts capped a year of remarkable political turbulence, even for a nation that has slogged through 18 coups along its often stumbling, eight-decade path toward democracy.

"I see this as a continuation of the crisis and the confrontation and the turmoil that we saw last year," said Chulalongkorn University political analyst Thitinan Pongsudhirak.

The battle for political control of this Southeast Asian nation began in the streets early last year, with months of peaceful protests against former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who was finally ousted by the military on Sept. 19.

The country breathed a sigh of relief after the coup, as army chief General Sonthi Boonyaratglin promised to restore democracy within a year and to root out the culture of corruption Thaksin was accused of creating.

Sonthi set up an interim government of mainly technocrats and launched a slate of peace initiatives to quell an insurgency by Muslim separatists in southern Thailand.

But public relief was short-lived. Insurgent violence in the south quickly grew bloodier and shadowy arsonists began burning schools in the northern Thai heartland, a one-time Thaksin stronghold.

Meanwhile Thai media, which had generally welcomed the coup, began to criticize the slow pace of investigations into alleged corruption in Thaksin's government and questioned the purpose of the military takeover.

Trust in the new government was badly shaken when its financial team sparked a market crash on Dec. 19 with a bungled attempt to control the baht.

The currency control measures were quickly eased, but public confidence was still on the wane when the explosions hit Bangkok. Thai stocks, which were Asia's worst performers last year, sank more than seven percent last week.

"We can see that the coup has gone wrong," Thitinan said.

"They did not conduct a decisive coup. It was a coup that left Thaksin and his cronies off the hook," Thitinan said.

Thaksin has been in exile since his ouster, but the military has not revoked his diplomatic passport -- allowing the billionaire to travel freely -- and has made little visible progress toward filing any formal charges against him.

Prime Minister Surayud Chulanont has accused factions linked to Thaksin of staging the bombings, which killed three people and wounded 42 others.

The government and analysts have generally ruled out southern insurgents as the culprits. But Defense Minister Boonrawd Somtas said on Thursday he believed the bombers were "men in uniform," meaning either police or military.

Hours after Boonrawd made the remarks, rumors of a counter-coup, or possibly a new coup by Sonthi against the very government he installed, swirled around the capital.

The rumors proved baseless, but highlighted the national case of the jitters.

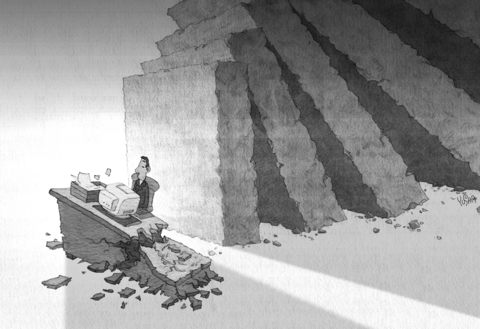

"It is a small group of people holding onto a large reserve of power," political analyst Panitan Wattanayagorn said of the junta. "They are very much looking like a fortress that is being attacked from all angles."

New bomb scares have rattled Bangkok for the past week and worries about a new power struggle have Thais bracing for another rocky year.

Many analysts have suggested that police or military who fell out of favor after the coup, but who are not directly aligned with Thaksin, could be behind the blasts.

"I am not convinced that the bombs were the work of former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra," said Thawee Surarithikul, dean of political science at Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University.

"But it could be the work of either police or military from the previous regime who lost their influence and power," he said.

The concern among many analysts is that the latest instability in Thailand could prompt the military to delay the drafting of a new constitution and postpone elections that had been promised for October.

"If the bombings were a one-off, they can regain control and get their act back together. Then the constitution timetable is still intact," Panitan said. "But obviously if the bomb threats continue, then the military might be forced to do something more drastic, like another coup."

Speaking at the Copenhagen Democracy Summit on May 13, former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) said that democracies must remain united and that “Taiwan’s security is essential to regional stability and to defending democratic values amid mounting authoritarianism.” Earlier that day, Tsai had met with a group of Danish parliamentarians led by Danish Parliament Speaker Pia Kjaersgaard, who has visited Taiwan many times, most recently in November last year, when she met with President William Lai (賴清德) at the Presidential Office. Kjaersgaard had told Lai: “I can assure you that ... you can count on us. You can count on our support

Denmark has consistently defended Greenland in light of US President Donald Trump’s interests and has provided unwavering support to Ukraine during its war with Russia. Denmark can be proud of its clear support for peoples’ democratic right to determine their own future. However, this democratic ideal completely falls apart when it comes to Taiwan — and it raises important questions about Denmark’s commitment to supporting democracies. Taiwan lives under daily military threats from China, which seeks to take over Taiwan, by force if necessary — an annexation that only a very small minority in Taiwan supports. Denmark has given China a

Many local news media over the past week have reported on Internet personality Holger Chen’s (陳之漢) first visit to China between Tuesday last week and yesterday, as remarks he made during a live stream have sparked wide discussions and strong criticism across the Taiwan Strait. Chen, better known as Kuan Chang (館長), is a former gang member turned fitness celebrity and businessman. He is known for his live streams, which are full of foul-mouthed and hypermasculine commentary. He had previously spoken out against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and criticized Taiwanese who “enjoy the freedom in Taiwan, but want China’s money”

A high-school student surnamed Yang (楊) gained admissions to several prestigious medical schools recently. However, when Yang shared his “learning portfolio” on social media, he was caught exaggerating and even falsifying content, and his admissions were revoked. Now he has to take the “advanced subjects test” scheduled for next month. With his outstanding performance in the general scholastic ability test (GSAT), Yang successfully gained admissions to five prestigious medical schools. However, his university dreams have now been frustrated by the “flaws” in his learning portfolio. This is a wake-up call not only for students, but also teachers. Yang did make a big