Schoolteacher Sherbahadur Tamang walks through the southern Nepalese village of Khetbari and describes what happened on Sept. 9: "During the night there was light rain but when we woke, its intensity increased. In an hour or so, the rain became so heavy that we could not see more than a meter in front of us. It was like a wall of water and it sounded like 10,000 lorries. It went on like that until midday. Then all the land started moving like a river."

When it stopped raining, Tamang and the village barely recognized their valley.

In just six hours the Jugedi River, which normally flows for only a few months of the year and is at most about 50m wide in Khetbari, had scoured a 300m-wide path down the valley, leaving a 3m-deep rockscape of giant boulders, trees and rubble in its path.

Hundreds of fields and terraces had been swept away. The irrigation systems built by generations of farmers had gone and houses were demolished or left uninhabitable. Tamang's house survived on a newly formed island.

The residents of Khetbari expect a small flood every decade or so, but what shocked the village was that two large ones have taken place in the last three years.

According to Tamang, a pattern is emerging: "The floods are coming more severely and more frequently. Not only is the rainfall far heavier these days than anyone has ever experienced, it is also coming at different times of the year."

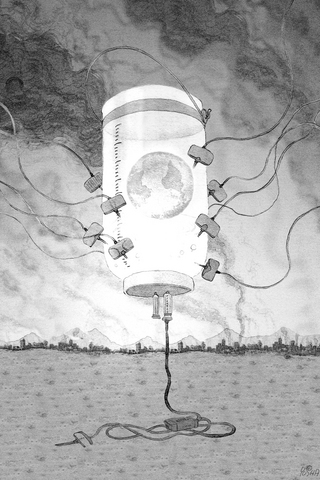

Nepal is on the front line of climate change and variations on Khetbari's experience are now being recorded in communities from the freezing Himalayas of the north to the hot lowland plains of the south. For some people the changes are catastrophic.

"The rains are increasingly unpredictable. We always used to have a little rain each month, but now when there is rain it's very different. It's more concentrated and intense. It means that crop yields are going down," says Tekmadur Majsi, whose land has been progressively washed away by the Tirshuli River.

Majsi now lives with 200 other refugees in tents in a small grove of trees by a highway.

In the south, villagers have many minute observations of a changing climate. One says that wild pigs in the forest now have their young earlier, another says that certain types of rice and cucumber will no longer grow where they used to and a third says that the days are hotter and that some trees now flower twice a year.

Such anecdotal observations are backed by scientists who are recording in Nepal some of the fastest long-term increases in temperatures and rainfall anywhere in the world.

At least 44 of Nepal's and neighboring Bhutan's Himalayan lakes, which collect meltwater from glaciers, are said by the UN to be growing so rapidly they they could flood over their banks within a decade.

Any climate change in Nepal reverberates throughout the region, as nearly 400 million people in northern India and Bangladesh also depend on rainfall and rivers that rise in Nepal.

"Unless the country learns to adapt, then people will suffer greatly," says Gehendra Gurung, a team leader with Practical Action in Nepal, which is trying to help people prepare for change.

In projects around the country, the organization is working with vulnerable villages, helping them build dykes and set up early warning systems. It is also teaching people to grow new crops, introducing drip irrigation and water storage schemes, trying to minimize deforestation which can lead to landslides and introducing renewable energy.

Some people are learning fast and are benefiting. Davandrod Kardigardi, a farmer in the Chitwan village of Bharlang, was taught to grow fruit and -- against his father's advice -- planted many banana trees.

As other farmers have struggled, he has increased his income.

But Nepal as a country needs help adapting to climate change, Gurung says.

The country's emissions of damaging greenhouse gases are negligible, yet it finds itself on the front line of climate change.

"Western countries can control their emissions but to mitigate the effects will take a long time. Until then they can help countries like Nepal to adapt. But it means everyone must question the way they live," he says.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion