Communism was behind some of the most mammoth economic disasters of the past century. This would be bad enough on its own, but the creed also claimed 100 million victims, a number greater that of all the wars in the 20th century. Meanwhile, a fifth of the world's population still lives under the yoke of communist regimes.

After escaping its own economic disasters from communist experiments, China is beginning to adopt the discredited theories and policies of a revived Keynesianism. As such, Beijing has traded class struggle and central planning for the dubious tools for the management of aggregate demand.

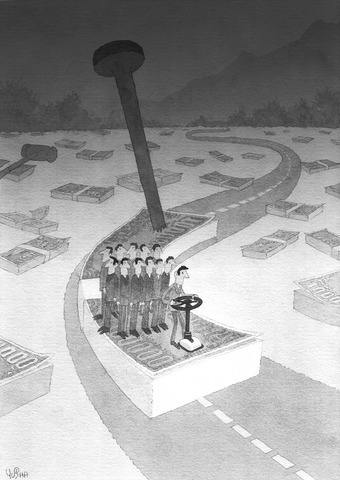

Like many of the advanced industrial economies, Beijing is showing signs of addiction to fiscal spending used for juicing current economic growth. Out of this has come growing deficits and ballooning public-sector debt that undermine China's long-term economic prospects.

One of the forgotten lessons of the Keynesian-inspired stagflation of the 1970s is that economic growth based on increased government spending is unsustainable. It also introduces distortions and imbalances in the overall production structure of the domestic economy. And this is exacerbated by China's special problem of endemic corruption that has ensured that much of its investment has brought low-quality economic growth.

Much of the massive spending has gone into fixed-asset purchases of capital expenditures for local-government or state-owned enterprises (SOEs). For its part, the central government accounts for more than two-thirds of investment spending in China. Recently, such expenditures have outpaced GDP growth by a multiple of three.

Adding to the pressures to expand central government deficits are plans for funding an expanded social welfare program as well as the need to address obligations arising from reform of the banking sector. Like other countries caught in the sway of Keynesian thinking, Historically, Beijing's use of fiscal stimulus has pushed up its budget deficits and expands its outstanding debt that bodes ill for the future.

Besides Beijing's large and growing deficits, there are other contingent liabilities that will balloon existing public-sector debt. These include recapitalizing state-owned banks and fulfilling pension obligations. Other government debt and total bad debts held by SOEs could push the ratio of public-sector debt to GDP up to 70 percent.

China's leaders are taking a dangerous course by trading long-term costs in exchange for short-term gains that are likely to be illusory in the bestcase. The harsh reality of public-sector deficit spending is future generations of taxpayers must repay money spent badly today. This will mean slower future economic growth and fewer employment opportunities for today's youth.

But Beijing is making a familiar and "rational" political choice to spend beyond its means in reaction to new political pressures. Higher levels of state spending are also motivated by a nagging deflationary cycle and a fear of a slowdown in economic growth.

As it is, judging the merits of deficit spending is a bit muddled. While it gives the appearance of providing some positive short-term economic results, it is counter-productive in the long-term when the bills have to be paid.

The best evidence of the failure of Keynesian cures is found in Japan. After its "bubble economy" collapsed at the end of the 1980s, Tokyo financed its additional public-sector expenditures with fiscal deficits. Japan's public-sector spending during the 1990s exceeded ?800 trillion (US$7 trillion), an amount five times greater than America's fiscal expenditures during its restructuring in the 1980s.

Nonetheless, neither massive expenditures nor the expansionary credit policies with a zero-interest rate worked very well. In the end, average economic growth in Japan during the 1990s was only about 1.1 per cent.

However, Tokyo's outstanding debt rose from 56 percent of GDP at the beginning of the 1990s to about at least 130 percent. Many independent observers and credit-rating agencies put the figure at a much higher level.

What happened in Japan was that public officials were either unaware or wary of initiating the needed radical restructuring of the domestic economy. If Beijing follows Tokyo down a similar path, the Chinese economy will slow down markedly in the medium to long term.

There are similarities in the necessary restructuring for these two economies. Both Japan and China have large numbers of small and medium-sized enterprises that cannot gain access to capital. But industrial dinosaurs are kept on life lines from banks.

Both countries also have high levels of personal savings, but the funds are allocated poorly and are often guided by political expediency rather than economic logic. Japan and China also suffer from weak domestic capital markets so that most borrowing goes through the banking system.

The problem is that bank lending is subject to political pressures that often leads to inefficient outcomes. Politicized decisions on the use of capital are at the heart of the financial sector problems.

Since capital markets require greater transparency and accountability, massive failures tend to be less likely. Consequently, both countries would be well served if they allowed their domestic stock and bond markets to become wider and deeper.

China and Japan must go beyond cutting costs to execute their economic restructuring since reductions tend to be limited to fixing temporary problems. Complete restructuring involves a dynamic perspective to implement fundamental changes in management and the scope of government involvement in the economy.

Changes are needed in their respective corporate and political cultures in Beijing and Tokyo so that policies evolve to encourage real entrepreneurial initiatives in the private sector.

Christopher Lingle is senior fellow at the Center for Civil Society in New Delhi and visiting professor of economics at Universidad Francisco Marroquin in Guatemala.

China badly misread Japan. It sought to intimidate Tokyo into silence on Taiwan. Instead, it has achieved the opposite by hardening Japanese resolve. By trying to bludgeon a major power like Japan into accepting its “red lines” — above all on Taiwan — China laid bare the raw coercive logic of compellence now driving its foreign policy toward Asian states. From the Taiwan Strait and the East and South China Seas to the Himalayan frontier, Beijing has increasingly relied on economic warfare, diplomatic intimidation and military pressure to bend neighbors to its will. Confident in its growing power, China appeared to believe

After more than three weeks since the Honduran elections took place, its National Electoral Council finally certified the new president of Honduras. During the campaign, the two leading contenders, Nasry Asfura and Salvador Nasralla, who according to the council were separated by 27,026 votes in the final tally, promised to restore diplomatic ties with Taiwan if elected. Nasralla refused to accept the result and said that he would challenge all the irregularities in court. However, with formal recognition from the US and rapid acknowledgment from key regional governments, including Argentina and Panama, a reversal of the results appears institutionally and politically

In 2009, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) made a welcome move to offer in-house contracts to all outsourced employees. It was a step forward for labor relations and the enterprise facing long-standing issues around outsourcing. TSMC founder Morris Chang (張忠謀) once said: “Anything that goes against basic values and principles must be reformed regardless of the cost — on this, there can be no compromise.” The quote is a testament to a core belief of the company’s culture: Injustices must be faced head-on and set right. If TSMC can be clear on its convictions, then should the Ministry of Education

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) provided several reasons for military drills it conducted in five zones around Taiwan on Monday and yesterday. The first was as a warning to “Taiwanese independence forces” to cease and desist. This is a consistent line from the Chinese authorities. The second was that the drills were aimed at “deterrence” of outside military intervention. Monday’s announcement of the drills was the first time that Beijing has publicly used the second reason for conducting such drills. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership is clearly rattled by “external forces” apparently consolidating around an intention to intervene. The targets of