In his History of European Morals, published in 1869, the Irish historian and philosopher W.E.H. Lecky wrote: "At one time the benevolent affections embrace merely the family, soon the circle expanding includes first a class, then a nation, then a coalition of nations, then all humanity and finally, its influence is felt in the dealings of man with the animal world."

The expansion of the moral circle could be about to take a significant step forwards. Francisco Garrido, a bioethicist and member of the Spanish parliament, has moved a resolution exhorting the government "to declare its adhesion to the Great Ape Project and to take any necessary measures in international forums and organizations for the protection of great apes from maltreatment, slavery, torture, death and extinction."

The resolution would not have the force of law, but its approval would mark the first time that a national legislature has recognized the special status of great apes and the need to protect them, not only from extinction, but also from individual abuse.

I founded the Great Ape Project together with Paola Cavalieri, an Italian philosopher and animal advocate, in 1993. Our aim was to grant some basic rights to the nonhuman great apes: life, liberty and the prohibition of torture.

The project has proven controversial. Some opponents argue that, in extending rights beyond our own species, it goes too far, while others claim that, in limiting rights to the great apes, it does not go far enough.

We reject the first criticism entirely. There is no sound moral reason why possession of basic rights should be limited to members of a particular species. If we were to meet intelligent, sympathetic extraterrestrials, would we deny them basic rights because they are not members of our own species? At a minimum, we should recognize basic rights in all beings who show intelligence and awareness [including some level of self-awareness] and who have emotional and social needs.

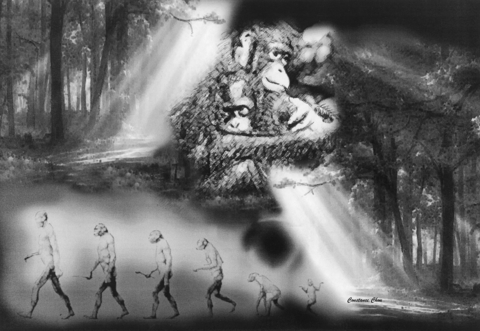

We are more sympathetic to the second criticism. The Great Ape Project does not reject the idea of basic rights for other animals. It merely asserts that the case for such rights is strongest in respect to great apes. The work of researchers like Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, Birute Galdikas, Frans de Waal and many others amply demonstrates that the great apes are intelligent beings with strong emotions that in many ways resemble our own.

Chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas have long-term relationships, not only between mothers and children, but also between unrelated apes. When a loved one dies, they grieve for a long time. They can solve complex puzzles that stump most two-year-old humans. They can learn hundreds of signs, and put them together in sentences that obey grammatical rules. They display a sense of justice, resenting others who do not reciprocate a favor.

When we group chimpanzees together with, say, snakes, as "animals," we imply that the gap between us and chimpanzees is greater than the gap between chimpanzees and snakes. But in evolutionary terms this is nonsense. Chimpanzees and bonobos are our closest relatives, and we humans, not gorillas or orangutans, are their closest relatives. Indeed, three years ago, a group of scientists led by Derek Wildman proposed, in the Pro-ceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, that chimpanzees have been shown to be so close to humans genetically that they should be included in the genus Homo.

Like any important and novel idea, Garrido's proposal has generated considerable debate in Spain. Some are concerned that it will interfere with medical research. But the only European biomedical research that has used great apes recently is the Biomedical Primate Research Centre at Rijswijk, in the Netherlands. In 2002, a review by the Dutch Royal Academy of Science found that the chimpanzee colony there was not serving any vital research purposes. The Dutch government subsequently banned biomedical research on chimpanzees. Thus, there is no European medical research currently being conducted on great apes, and one barrier to granting them some basic rights has collapsed.

Some of the opposition stems from misunderstandings. Recognizing the rights of great apes does not mean that they all must be set free, even those born and bred in zoos, who would be unable to survive in the wild. Nor does it rule out euthanasia if that is in the interest of individual apes whose suffering cannot be relieved. Just as some humans are unable to fend for themselves and need others to act as their guardians, so, too, will great apes living in the midst of human communities. What extending basic rights to great apes does mean is that they will cease to be mere things that can be owned and used for our amusement or entertainment.

A final group of opponents recognizes the strength of the case for extending rights to great apes, but worries that this may pave the way for the extension of rights to all primates, or all mammals, or all animals. They could be right. Only time will tell. But that is irrelevant to the merits of the case for granting basic rights to the great apes. We should not be deterred from doing right now by the fear that we may later be persuaded that we should do right again.

Peter Singer is professor of bioethics at Princeton University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

After 37 US lawmakers wrote to express concern over legislators’ stalling of critical budgets, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) pledged to make the Executive Yuan’s proposed NT$1.25 trillion (US$39.7 billion) special defense budget a top priority for legislative review. On Tuesday, it was finally listed on the legislator’s plenary agenda for Friday next week. The special defense budget was proposed by President William Lai’s (賴清德) administration in November last year to enhance the nation’s defense capabilities against external threats from China. However, the legislature, dominated by the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), repeatedly blocked its review. The

In her article in Foreign Affairs, “A Perfect Storm for Taiwan in 2026?,” Yun Sun (孫韻), director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said that the US has grown indifferent to Taiwan, contending that, since it has long been the fear of US intervention — and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) inability to prevail against US forces — that has deterred China from using force against Taiwan, this perceived indifference from the US could lead China to conclude that a window of opportunity for a Taiwan invasion has opened this year. Most notably, she observes that

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) said on Monday that it would be announcing its mayoral nominees for New Taipei City, Yilan County and Chiayi City on March 11, after which it would begin talks with the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) to field joint opposition candidates. The KMT would likely support Deputy Taipei Mayor Lee Shu-chuan (李四川) as its candidate for New Taipei City. The TPP is fielding its chairman, Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌), for New Taipei City mayor, after Huang had officially announced his candidacy in December last year. Speaking in a radio program, Huang was asked whether he would join Lee’s