This month, water once again takes center stage at the 4th World Water Forum in Mexico City. It is an opportune moment: While much of the world's attention has been fixed on issues of energy supply and security, hundreds of millions of people in the developing world continue to see the supply and security of fresh water as equally, if not more, important.

Surveys undertaken by the World Bank in developing countries show that when poor people are asked to name the three most important concerns they face, "good health" is always mentioned. And a key determinant of whether they will have good health or not is access to clean water.

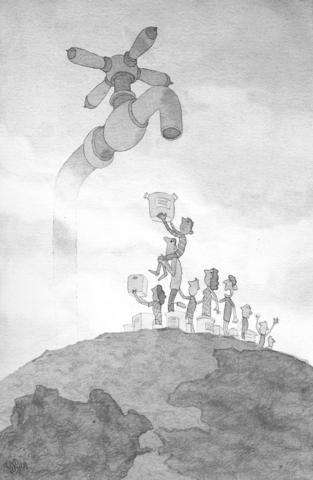

More than a billion people around the world today do not. As a result, they are increasingly vulnerable to poor health. The World Bank estimates that by 2035, as many as 3 billion people, almost all of them in developing countries, could live under conditions of severe water stress, especially if they happen to live in Africa, the Middle East or South Asia. This will cause obvious hardship, but it will also hold back the economic growth needed for millions of people to escape poverty.

In Latin America, about 15 percent of the population -- roughly 76 million people -- do not have access to safe water, and 116 million people do not have access to sanitation services. The figures are worse in Africa and parts of Asia.

This is a situation that few people in rich countries face. Generally, these countries' citizens enjoy services that provide for all water needs, from drinking to irrigation to sanitation. In addition, other water-related issues, such as the risks posed by flooding, have been reduced to manageable levels.

Rich nations have invested early and heavily in water infrastructure, institutions and management capacities. The result, beyond the health benefits for all, has been a proven record of economic growth; one only has to look at investment in hydropower to see the positive impact of water management projects on many economies.

Granted, rich countries have a certain advantage: They benefit from generally moderate climates, with regular rainfall and relatively low risks of drought and flooding. Even so, they are not immune to water-related disasters, as Hurricane Katrina's destruction of New Orleans taught us.

But the impact of such events on poor countries is much greater. Extreme rainfall variations, floods and droughts can have huge social and economic effects and result in the large-scale loss of life. The Gulf coast of Mexico and Central American countries have repeatedly experienced such tragedies, with poor communities the most vulnerable and the least able to cope.

Ethiopia and Yemen are equally stark examples. Ethiopia's development potential is closely tied to seasonal rains, so high rainfall variation, together with a lack of infrastructure, has undermined growth and perpetuated poverty. A single drought can cut growth potential by 10 percent over an extended period. Yemen, for its part, has no perennial surface water; its citizens depend entirely on rainfall, groundwater, and flash flooding.

To move forward, developing countries need new water infrastructure and better management. Any approach must be tailored to the circumstances of each country and the needs of its people, but there is no fundamental constraint to designing water development investments that ensure that local communities and the environment gain tangible and early benefits.

In some countries, new water infrastructure may mean canals, pumping stations and levees. Other nations might need deeper reservoirs, more modern filtration plants or improved water transport schemes. These can all potentially be designed to improve and expand water supplies for power generation, irrigation, and household and industrial use, while providing security against droughts and protection from floods.

The key to successfully increasing investment in water infrastructure is an equal increase of investment in water institutions. Badly managed infrastructure will do little to improve peoples' health or support economic growth, so water development and water management must go hand in hand. Water infrastructure can and must be developed in parallel with sound institutions, good governance, attention to the environment and an equitable sharing of costs and benefits.

A water investment policy that reduces the vulnerability of the poor and offers basic water security for all will require customized planning and an effective partnership of donor countries, developing country governments, the private sector and local communities.

Delegates to the World Water Forum will have ample opportunity to forge and/or strengthen these partnerships. If they succeed, the rewards for the world's poor will be immense.

Katherine Sierra is vice president for infrastructure at the World Bank.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

China’s recent aggressive military posture around Taiwan simply reflects the truth that China is a millennium behind, as Kobe City Councilor Norihiro Uehata has commented. While democratic countries work for peace, prosperity and progress, authoritarian countries such as Russia and China only care about territorial expansion, superpower status and world dominance, while their people suffer. Two millennia ago, the ancient Chinese philosopher Mencius (孟子) would have advised Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) that “people are the most important, state is lesser, and the ruler is the least important.” In fact, the reverse order is causing the great depression in China right now,

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

This should be the year in which the democracies, especially those in East Asia, lose their fear of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) “one China principle” plus its nuclear “Cognitive Warfare” coercion strategies, all designed to achieve hegemony without fighting. For 2025, stoking regional and global fear was a major goal for the CCP and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA), following on Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) Little Red Book admonition, “We must be ruthless to our enemies; we must overpower and annihilate them.” But on Dec. 17, 2025, the Trump Administration demonstrated direct defiance of CCP terror with its record US$11.1 billion arms

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other