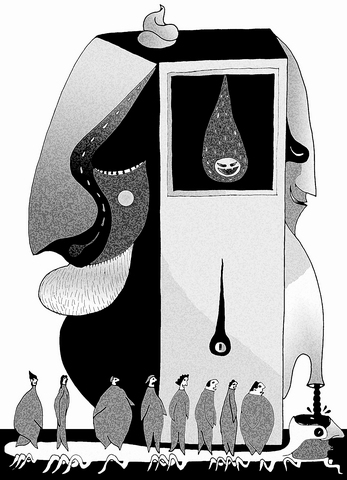

Gerhard Schroeder, who less than a month ago was Germany's chancellor, has agreed to become chairman of the company that is building a gas pipeline from Russia, across the Baltic Sea to Germany, and on through Western Europe. In many countries, Schroeder would now be charged with the crime of conflict of interest. His apparent ethical lapse is magnified by the fact that, at this very moment, Russia is threatening to cut off Ukraine's gas supplies if that country does not give in to the pricing demands of the Kremlin's state-owned gas behemoth, Gazprom.

Russia's strategic task is obvious: cutting off Ukraine's gas currently means cutting off much of Europe's gas as well, because some of its biggest gas pipelines pass through Ukraine. By circumventing Ukraine, Poland and, of course, the Baltic countries, the new pipeline promises greater leverage to the Kremlin as it seeks to reassert itself regionally. Russian President Vladimir Putin and his administration of ex-KGB clones will no longer have to worry about Western Europe when deciding how hard to squeeze Russia's postcommunist neighbors.

Should Europe really be providing Putin with this new imperial weapon? Worse, might Russia turn this weapon on an energy-addicted EU? That a German ex-chancellor is going to lead the company that could provide Russia with a means to manipulate the EU economy is testimony to Europe's dangerous complacency in the face of Putin's neo-imperialist ambitions.

Certainly Russia's media are aware of Europe's growing dependence on Russian energy. Indeed, they revel in it: after we integrate and increase our common gas business, Russian editorialists write, Europe will keep silent about human rights. Putin expresses this stance in a more oblique way with his commitment to pursuing what he calls an "independent policy." What he means by that is that Russia is to be "independent" of the moral and human rights concerns of the Western democracies.

Perhaps some European leaders really do believe that maintaining the EU's cozy prosperity justifies silencing ourselves on human rights and other issues that annoy the Kremlin. Of course, we may speak up, briefly, about "commercial" matters like the expropriation of Yukos, but if the Kremlin puts a price on our values or criticism of Russian wrongdoing -- as in, say, bloodstained Chechnya -- Europeans seem willing to shut up rather than face the possibility of higher energy prices, or even a blockade like that now facing Ukraine.

As Putin shuffles his court, subordinating the Duma to his will, the EU's hopes for a growing "Europeanization" of Russia should be abandoned. The Russia that Putin is building has mutated from the post-Soviet hopes of freedom into an oil and gas bulwark for his new model ex-KGB elite. Indeed, Matthias Warnig, the chief executive of the pipeline consortium that Schroeder will chair, is a longtime Putin friend. The Wall Street Journal reported earlier this year that Warnig, who heads Dresdner Bank's Russian arm, was an officer in the Stasi, the East German secret police, and met Putin in the late 1980's when the Russian president was based in East Germany as a KGB spy.

That Russians tolerate a government of ex-KGB men, for whom lack of compassion and intolerance of dissent are the norm, reflects their exhaustion from the tumult of the last 20 years. Now the Kremlin seems to think that what is good for ordinary Russians is good for independent nations as well: small and weak countries will be shown no mercy once Russia is given the tools to intimidate, isolate, and threaten them with the prospect of an energy blockade. As a former Head of State of newly independent Lithuania, I frequently endured such threats.

The EU has signed numerous agreements with Russia including one for a "common space" for freedom and justice. The Kremlin is very good at feigning such idealism. Its control of Eastern Europe was always enforced on the basis of "friendship treaties," and the Soviet invasions of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968 were "fraternal" missions.

But look how Putin abuses that "common" space: barbaric treatment of Chechens, the businessman Mikhail Khodorkovsky jailed, foreign NGO's hounded, a co-leader of last year's Orange Revolution, Yuliya Tymoshenko, indicted by Russian military prosecutors on trumped-up charges. If Europeans are serious about human rights and freedoms, they must recognize that those values are not shared by Putin's Kremlin.

The same is true of viewing Russia as an ally in the fight against terrorism. Is it really conceivable that the homeland of the "Red Terror" with countless unpunished crimes from the Soviet era, and which bears traces of blood from Lithuania to the Caucasus, will provide reliable help in stopping Iran and North Korea from threatening the world? It seems more likely that the Kremlin's cold minds will merely exploit each crisis as an opportunity to increase their destructive power and influence.

For decades, my region of Europe was left to the mercy of evil. So I cannot sit back in silence as Europe stumbles blindly into a new appeasement. We, the new democracies of Eastern Europe, have been taught by our legacy that behind Russia's every diplomatic act lurks imperial ambition.

Western Europeans, who have been spared this legacy, should heed our warnings. Dependence on Russia -- even if its face is now that of the allegedly "charismatic" Gerhard Schroeder -- will only lead to an abyss.

Vytautas Landsbergis, independent Lithuania's first president, is a European parliamentarian.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its