This week a firm called Teddyfone launched a teddy-bear- shaped mobile phone aimed at four-to-eight-year-olds, just in time for Christmas.

At the same time, it launched the i-Kids satellite mobile phone, which looks a bit like a spaceman and incorporates the latest global positioning satellite (GPS) technology, allowing you to track your child's movements through a secure website -- or from your own mobile phone -- to a radius of 20m to 50m.

These are just two new additions to the latest parenting growth industry: a multimillion-dollar market in new and increasingly flashy "child-tracking" devices.

Using fast-developing mobile phone, wireless, radio, microchip and GPS technology, these new inventions will enable us to keep tabs on our children wherever they are, night or day.

In the UK, for example, child-tracking is currently focused on mobiles. Earlier this year Mymo, the first mobile phone aimed at very young kids, was taken off the market after William Stewart, the chairman of the UK Health Protection Agency, warned that children under eight could absorb too much radiation from mobile phones.

Despite such warnings, however, in March it was reported that the average age of British children owning their first mobile phone had fallen from 12 to eight in only four years, and that more than a million children aged five to nine had a mobile. Mymo was repackaged and relaunched as the Owl phone (an "emergency phone" for children), and if industry predictions are right, another half a million children should be signed up to mobile devices by 2007.

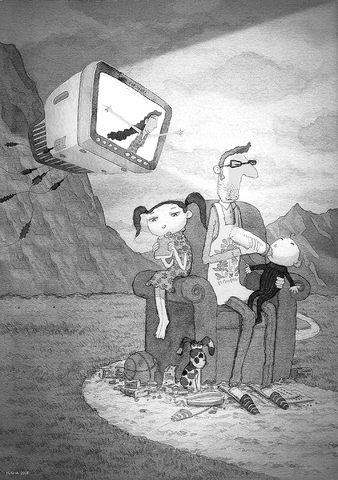

But why? Certainly, around Christmas parents are more likely to cave in to whining requests for a new Baby Annabel, a Tamagotchi or a cuddly animal-shaped mobile phone. But there's more to it than naked materialism. The trend seems to be more about protection than possession: We believe these devices will help to keep our children safe in what is, we perceive, an increasingly scary, predatory world.

And we're prepared to pay.

The i-Kids phone allows parents to select a "Safety Zone Alert" -- an area on the map surrounding the place where your child is meant to be. You are then alerted by text if the phone leaves the zone.

"The world is a more dangerous place than it used to be," says Paul Liesching, managing director of Teddyfone, "and these devices give children more freedom; maybe they'll be able to play in the park, like they used to."

KidsOK, the first mobile child-tracking service to hit the high street, recently became available in shops including Boots, BHS and Toys R Us. To track your child using the KidsOK package, you simply "ping" his/her phone -- it will work on any handset -- by sending a two-word text to KidsOK. You wait a few seconds and a map "pings" back to your mobile showing the location of your child's handset.

The technology is relatively straightforward. When a mobile is on, every minute or so the handset communicates with the network operator to check it has reception and to find the nearest mast. This means operators always know, within a certain radius, where any handset is.

Apart from the obvious fact that your child's handset could be lying in the mud, may have run out of power or been stolen (or removed), there are limitations to current phone-tracking technology: GPS won't work if the phone is in a building or underground, and clouds and trees can also interfere. While standard "cell technology" on mobile phones works anywhere there are masts, it is less accurate than GPS.

The phone network only knows roughly where a handset is by working out a point between local phone masts. This means that in the city you can pinpoint a phone by about 500m but in the countryside it could be a 4km-7km radius.

"These levels of accuracy are peace of mind levels," says Richard Jelbert, the chief executive of KidsOK.

"The product won't stop anything bad happening, or absolutely confirm that all is OK. But it is another tool you can use, alongside texting or calling, to give you the extra ability to check that your child is OK," he says.

Some argue that this is all a bit "big mother-ish" and ultimately pointless given how easy it is to lose a mobile. But according to Michelle Elliot, the director of the UK children's protection charity Kidscape (which endorses KidsOK), tracking technology can be reassuring for children as well as their parents.

"Many children do like the security of knowing their parents are there -- it's about peace of mind for both parent and child," he says.

Indeed, much of this technology is two-way: Last week KidsOK launched "ping alert" (anyone with a mobile can sign up on www.pingalert. com). If you sign up, the number 5 on your child's phone, which has a dimple on it on all mobiles, becomes a panic button. In a sticky spot your child simply holds 5 down and your mobile is sent a map and an alert message.

But all this is distinctly small fry compared to developments in the US where electronic tagging is the latest child-tracking buzz.

In the UK, electronic tags -- or "radio frequency identification" (RFID) tags -- are mostly being used on early release prisoners, or being investigated as a possible alternative to barcodes in shops. In the States, meanwhile, one San Diego company, Smart Wear Technologies, is launching "Home Alarm" next year.

Small, high-frequency RFID tags act as your child's "unique digital ID" and can be simply sewn, like name tags, into pyjamas or clothes. Sensors attached to the doors and windows of your house create "an invisible barrier" -- if your tagged child "breaches the boundary" an alarm sounds.

In Silicon Valley, Wherify Wireless was until recently selling a US$200 watch that picks up GPS signals, as well as a child's GPS -- implanted backpack, priced US$900. These products have now been replaced by its Wherifone -- a small GPS mobile aimed at teens and pre-teens -- largely because parents wanted the two-way calling feature.

Elsewhere, Teen Arrive Alive, Ulocate and DriveDiagnostics have developed special car-tracking devices that use GPS technology to locate the exact whereabouts, speed and direction of your newly qualified teenage driver. Even Microsoft was recently showing off a "cyber-teddy" that "watches" your child with glassy, microchip -- implanted eyes. But do we want this sort of thing?

In the UK, it seems we do. In 2003 a think tank, the Future Foundation, conducted a survey that found 75 percent of British parents would buy an electronic bracelet to trace their child's movements if they could.

"The potential for this sort of technology is huge," says a Future Foundation spokesperson. "The climate is shifting -- we have a whole generation of teens growing up now whose parents expect to know where they are at all times."

It is hardly surprising technology companies are cashing in, agrees Frank Furedi, author of The Politics of Fear.

"These technologies give the illusion of control," he says, and despite the fact that statistically the world is no more dangerous now for children than it was at the start of the 20th century, "fear has become the common currency of life. Nowadays, if you want parents to do anything -- or buy anything -- you simply prey on their fears."

So how scared are we? John Davidson, the chief executive of a Newcastle-based company, Globalpoint Technologies, believes we're ready for the next step.

This month his company released an anti-abduction device called the "Personal Companion" -- a slim band that folds round your child's arm (hidden under her clothes) and uses a combination of mobile phone and GPS technology to enable you to track her within two metres.

If in trouble, your child can simply squeeze the band, which then automatically calls your mobile, allowing your child to speak to you, or if your child can't speak, letting you listen in to what's happening (and, crucially, find out where).

The band is expensive (from ?450) and has the usual GPS limitations, but, says Davidson, "without a doubt this is a mass market for us. The technology is becoming cheaper every day and is developing all the time."

Clearly, then, child-tracking is in its infancy. How far we're prepared to go with this kind of surveillance remains to be seen. But teddy-bear phones are surely just the beginning.

There is a modern roadway stretching from central Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, to the partially recognized state’s Egal International Airport. Emblazoned on a gold plaque marking the road’s inauguration in July last year, just below the flags of Somaliland and the Republic of China (ROC), is the road’s official name: “Taiwan Avenue.” The first phase of construction of the upgraded road, with new sidewalks and a modern drainage system to reduce flooding, was 70 percent funded by Taipei, which contributed US$1.85 million. That is a relatively modest sum for the effect on international perception, and

When former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) first took office in 2016, she set ambitious goals for remaking the energy mix in Taiwan. At the core of this effort was a significant expansion of the percentage of renewable energy generated to keep pace with growing domestic and global demands to reduce emissions. This effort met with broad bipartisan support as all three major parties placed expanding renewable energy at the center of their energy platforms. However, over the past several years partisanship has become a major headwind in realizing a set of energy goals that all three parties profess to want. Tsai

At the end of last year, a diplomatic development with consequences reaching well beyond the regional level emerged. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared Israel’s recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state, paving the way for political, economic and strategic cooperation with the African nation. The diplomatic breakthrough yields, above all, substantial and tangible benefits for the two countries, enhancing Somaliland’s international posture, with a state prepared to champion its bid for broader legitimacy. With Israel’s support, Somaliland might also benefit from the expertise of Israeli companies in fields such as mineral exploration and water management, as underscored by Israeli Minister of

An elderly mother and her daughter were found dead in Kaohsiung after having not been seen for several days, discovered only when a foul odor began to spread and drew neighbors’ attention. There have been many similar cases, but it is particularly troubling that some of the victims were excluded from the social welfare safety net because they did not meet eligibility criteria. According to media reports, the middle-aged daughter had sought help from the local borough warden. Although the warden did step in, many services were unavailable without out-of-pocket payments due to issues with eligibility, leaving the warden’s hands