A long with a group of faculty, staff and students from my university in Islamabad, I journeyed to Balakot, close to the center of the Kashmir earthquake.

This mountainous town, situated on the banks of the Kunhar River, has been destroyed. There is rubble and the gut-wrenching smell of decaying corpses. The rats have it good; the one I accidentally stepped upon was already fat. If there is a plan to clear the concrete rubble in and around the town, nobody seems to have any clue. But the Balakotis are taking it in their stride -- nose masks are everywhere.

But there is good news. We were just one of countless groups of ordinary citizens that were on the move after the enormity of last Saturday's earthquake became apparent. The Mansehra to Balakot road, finally forced open by huge army bulldozers, is now lined with relief trucks bursting with supplies that were donated by people from across the country. This is one of those rare times that I have seen Pakistan's people feel and move together as a nation. Even the armed bandits who waylay relief supplies -- making necessary a guard of soldiers with automatic weapons, standing every few hundred yards -- cannot destroy this moment.

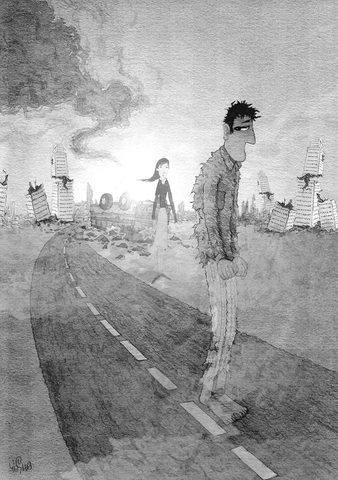

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Islamic groups from across the country have also arrived.? Some bring relief supplies; others simply harangue those who have lost loved ones and livelihoods, lecturing that their misdeeds brought about this catastrophe. None seem to have an explanation for why God's wrath was especially directed to mosques, madrassas, and schools -- all of which collapsed in huge numbers. None say why thousands of the faithful have been buried alive in this sacred month of fasting.

Aid from across the world is making its way towards the destruction, and the US is here, too. Double-bladed Chinook helicopters, diverted from fighting al-Qaeda in Afghanistan, now fly over the heartland of jihad and the militant training camps in Mansehra to drop food and tents a few miles beyond. Temporarily birds of peace instead of war, they do immensely more to calm angry Islamists than the reams of glossy propaganda put out by the US information services in Pakistan.

Their visibility makes relief choppers terrific propaganda, for good or for worse. This is undoubtedly why the Pakistani government refused an Indian offer to send in helicopters for relief work in and around Muzzafarabad, the flattened capital of Pakistani-administered Kashmir. Sadly, in spite of a much-celebrated peace process, Pakistan refuses visas to Indian peace groups and activists that seek to help in the relief effort. It is still not too late to open this door and let Pakistanis, Indians and Kashmiris help each other.?

The challenges are many. The aid remains too little. There are not enough tents, blankets, and warm clothes to go around.? Hundreds of tent clusters have come up, but thousands of families remain out under the skies, facing rain and hail, and with dread in their hearts.

These families have lost everything but the tattered clothes on their backs. Some even lost the land they had lived upon for generations -- the top soil simply slid away, leaving behind hard rock and rubble.

Worst of all, aid is not reaching those most affected. Hundreds of destroyed communities are scattered deep in the mountains. We saw helicopters attempt aerial drops; landing is impossible in most places. But people told us that they often miss and the supplies land up thousands of feet or below in deep forests. Distribution is haphazard and uncoordinated, done with little thought. We saw relief workers throw packets of food and clothes from the top of trucks, causing a riot. Hustlers thrive, the weak watch passively.

The clock is ticking. In two months, the mountains will get their first snowfall and temperatures will plummet below zero. Millions may have been made homeless. Those without shelter will die. Tents will not do.

From a special university fund, we pledged to rebuild the homes of a dozen families. But ten thousand or more families will need homes in the Mansehra-Balakot-Kaghan area alone, not to speak of adjoining Kashmir. The task of saving lives has barely begun.

For me personally, there is a sense of deja vu. Nearly 31 years ago, on Dec. 25, 1974, a powerful earthquake flattened towns along the Karakorum Highway and killed nearly 10,000 people. I traveled with a university team into the same mountains for similar relief work. Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto had made a passionate appeal for funds around the world, had taken a token helicopter trip to the destroyed town of Besham, and then made fantastic promises of relief and rehabilitation.

Hundreds of millions of dollars in relief funds received from abroad mysteriously disappeared. Some well-informed people believe that those funds were used to kick off Pakistan's secret nuclear program.

Will today's government do better? This will only be assured if citizens organize themselves to play a more direct role in relief and rehabilitation for the long term. Civil society groups must now assert themselves. They must demand a voice in planning and implementing the reconstruction effort and, along with international donors, transparency and public auditing of where aid is spent.

Pervez Hoodbhoy is a professor at Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan. Copyright: Project Syndicate

There is a modern roadway stretching from central Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, to the partially recognized state’s Egal International Airport. Emblazoned on a gold plaque marking the road’s inauguration in July last year, just below the flags of Somaliland and the Republic of China (ROC), is the road’s official name: “Taiwan Avenue.” The first phase of construction of the upgraded road, with new sidewalks and a modern drainage system to reduce flooding, was 70 percent funded by Taipei, which contributed US$1.85 million. That is a relatively modest sum for the effect on international perception, and

At the end of last year, a diplomatic development with consequences reaching well beyond the regional level emerged. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared Israel’s recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state, paving the way for political, economic and strategic cooperation with the African nation. The diplomatic breakthrough yields, above all, substantial and tangible benefits for the two countries, enhancing Somaliland’s international posture, with a state prepared to champion its bid for broader legitimacy. With Israel’s support, Somaliland might also benefit from the expertise of Israeli companies in fields such as mineral exploration and water management, as underscored by Israeli Minister of

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,