Governments around the world want to promote entrepreneurship. Though most business start-ups will never amount to much, each little company is an experiment, and a great deal of experimentation is necessary to produce the occasional firm that can transform a nation's economy -- or even rise to international significance. In short, entrepreneurship is an incubator, and one that is essential to long-term economic success.

In explaining the variation in levels of entrepreneurship across countries, much attention is devoted nowadays to differences in national attitudes and policies. But there are also significant differences in levels of entrepreneurship within individual countries. People from Shanghai are said to be more entrepreneurial than people in Beijing. People in the Ukrainian town of Kherson are more entrepreneurial than people from Kiev.

In a recent study, Mariassunta Giannetti and Andrei Simonov of the Stockholm School of Economics show the magnitude of differences in levels of entrepreneurship across Swedish municipalities. They define entrepreneurs as people who report income from a company that they control and work in at least part-time, and find that the proportion of entrepreneurs in the population differs substantially across the 289 municipalities that they studied, ranging from 1.5 percent to 18.5 percent.

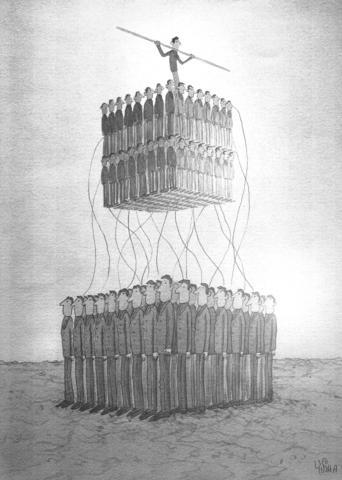

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

What can these differences tell us about the real causes of entrepreneurship?

Policy changes at the national level cannot account for the variation Gianetti and Simonov found. In the 1980s and early 1990s, centralized wage-setting agreements were dissolved and the Swedish government cut personal and corporate tax rates. The level of entrepreneurial activity in the country as a whole doubled as a result, but the response was very different from one municipality to another. Why?

Cultural variables seem to explain a lot: Religion and politics accounted for about half of the variation across municipalities. Municipalities tended to have more entrepreneurs if they had a high proportion of pensioners who were members of the Church of Sweden (the official state church until 2000) and a high proportion of right-wing voters.

Beyond that, a feedback mechanism appears to be in place: Cities with more entrepreneurs tend to beget still more entrepreneurs. Once an entrepreneurial culture takes root, it typically spreads locally, as people learn about business and begin to feel attracted by it -- even if it doesn't yield an immediate or certain payoff.

Indeed, Giannetti and Simonov discovered that the average income of entrepreneurs was lower in high-entrepreneurship municipalities than in the low-entrepreneurship ones. Similarly, studies from other countries show that entrepreneurs often have lower initial earnings and earnings growth than they would have as employees. What these studies suggest is that differences in the degree of entrepreneurship may be due less to better economic opportunities (the "supply" side of the entrepreneurship equation) than to cultural differences that make entrepreneurship personally more rewarding (the "demand" side).

This hypothesis is supported by Giannetti and Simonov, who argue that differences in the prestige of entrepreneurs across municipalities may account for differences in levels of entrepreneurship. In some municipalities, entrepreneurs enjoy high social status, regardless of whether they are already successful; elsewhere they are looked down upon and other occupations are more admired.

The idea that prestige is important is not new. In her book Money, Morals and Manners, the sociologist Michele Lamont compared definitions of success in France and the US. She interviewed people in both countries and asked them what it meant to be a "worthy person." In essence, she was asking people about their sense of what is important in life and about their own personal sense of identity.

Lamont's study confirmed the conventional wisdom that Americans value business success, while the French place greater value on culture and quality of life. Likewise, open contempt of "money-hungry" businesspeople and competition is expressed more often in France than in the US.

But, while Lamont focused on differences between the French and the Americans, her study's most interesting finding was that of significant differences between regions within France. She compared Clermont-Ferrand, the capital of Auvergne, in the center of France, with Paris. Auvergne's inhabitants have a reputation for being parsimonious and stern, and, despite substantial recent progress, for a relative dearth of high culture.

Lamont found that people in both Paris and Clermont-Ferrand tended to express contempt for "money-grubbing." But the Clermontois valued "simplicity, pragmatism, hard work and resolve," while the Parisians put more stress on "pizzazz and brilliance." She concluded that, "In many respects the Clermontois are closer to the Hoosiers (as the residents of the US mid-Western state of Indiana are called) than to the Parisians." Her evidence suggests that in Clermont-Ferrand, as compared to Paris, there is a higher intrinsic demand for starting small businesses.

Virtually every country is a pastiche of local cultures that differ in how they motivate people and shape their personal identity. Differences in how these cultures define what it means to be a worthy person, and how worthiness is signaled, probably explain much of the variation in levels of entrepreneurship.

Economists and others often tend to look at countries as a whole and emphasize national attitudes and national policies as the main factors in encouraging or discouraging entrepreneurship. But, in fact, the national success in entrepreneurship depends on the evolution of local cultures and their interaction with national policies. Entrepreneurship can take root in culturally congenial regions of any country after economic barriers against it are lifted, and then feed on itself to grow to national significance.

Robert Shiller is professor of economics at Yale University, director at Macro Securities Research LLC, and author of Irrational Exuberance and The New Financial Order: Risk in the 21st Century.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

Eighty-seven percent of Taiwan’s energy supply this year came from burning fossil fuels, with more than 47 percent of that from gas-fired power generation. The figures attracted international attention since they were in October published in a Reuters report, which highlighted the fragility and structural challenges of Taiwan’s energy sector, accumulated through long-standing policy choices. The nation’s overreliance on natural gas is proving unstable and inadequate. The rising use of natural gas does not project an image of a Taiwan committed to a green energy transition; rather, it seems that Taiwan is attempting to patch up structural gaps in lieu of

News about expanding security cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, including the visits of Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) in September and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) this month, as well as growing ties in areas such as missile defense and cybersecurity, should not be viewed as isolated events. The emphasis on missile defense, including Taiwan’s newly introduced T-Dome project, is simply the most visible sign of a deeper trend that has been taking shape quietly over the past two to three years. Taipei is seeking to expand security and defense cooperation with Israel, something officials

“Can you tell me where the time and motivation will come from to get students to improve their English proficiency in four years of university?” The teacher’s question — not accusatory, just slightly exasperated — was directed at the panelists at the end of a recent conference on English language learning at Taiwanese universities. Perhaps thankfully for the professors on stage, her question was too big for the five minutes remaining. However, it hung over the venue like an ominous cloud on an otherwise sunny-skies day of research into English as a medium of instruction and the government’s Bilingual Nation 2030