Those of us who know that long-run fiscal imbalances are likely to end in disaster -- high inflation, deep recession, financial crisis, or all three -- scratch our heads in bemusement at the priorities of George W. Bush and his administration. The Social Security "crisis" that he wants to spend his political capital on "resolving" ranks no higher than third among America's fiscal problems in urgency and seriousness -- and at a time when these problems have grown into a profound threat to global economic stability.

America's gravest fiscal problem is the short- and medium-run deficit between tax revenues and spending. This deficit is entirely of Bush's own creation, having enacted -- and now seeking to extend -- tax cuts that are not cuts at all, because they merely shift the burden of fiscal consolidation onto future generations.

The second most serious problem is the looming long-term explosion in the costs of America's healthcare programs. This is also partly Bush's doing, or, rather, not doing, as his first-term policy on health spending was to do virtually nothing to encourage efficiency and cost containment. Instead, he enacted a Medicare drug benefit that promises to spend enormous amounts of money for surprisingly little in the way of better healthcare.

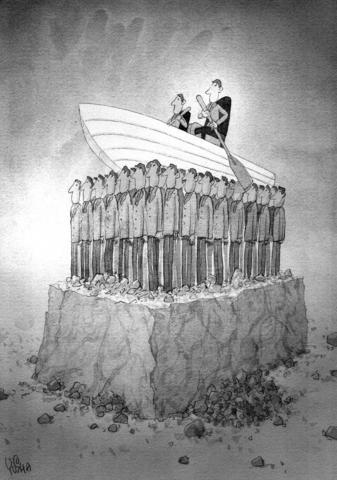

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Surely a more competent administration would be worried about addressing these more severe and urgent fiscal problems. Let's pretend that the United States had such a government. What would it do?

Dealing with the short- and medium-run deficit would be fairly straightforward: decide how large a share of GDP the federal government should take up, set spending at that level, and set taxes so that the budget is balanced (or so that the debt-to-GDP ratio is not growing) over the business cycle. Determine whether, overall, you would rather have in the medium term a federal government that spends, say, 16 percent, 20 percent, or 24 percent of GDP -- and on what.

What is not straightforward is how to address the imminent explosion of healthcare costs. In fact, projections of rapidly rising Medicare and Medicaid spending in the US -- and similarly rapidly-rising governmental healthcare expenditures elsewhere in the developed world -- are not so such a problem to be solved as the side effects of an opportunity to be grasped.

The opportunity stems from the fact that our doctors and nurses, our pharmacists and drug researchers, our biologists and biochemists are learning to do wonderful things. Many of these things are, and will be, expensive. Many of them will also be desirable: longer, healthier, and higher quality lives as we learn more about the details of human biology. Federal healthcare spending will grow very rapidly over the next two generations because the things that healthcare money will be spent on will be increasingly wonderful, and increasingly valued.

But it will be difficult to grasp fully this opportunity. It is highly likely that desired health expenditures will be enormous for some things and trivial for others. This calls for insurance. The problem is that private insurance markets do not work well when the buyer knows much more about what is being insured than the seller. Obviously, one's health is an area in which private information can be very private indeed.

This is, of course, why state-run healthcare systems came into being. But replacing private insurance with public insurance has its own problems: consider the parlous circumstances in which Britain's National Health System finds itself, the result of generations of politically driven underinvestment in healthcare.

Moreover, the overall level of spending is likely to be large. That means that without (and even with) state-run healthcare systems, the rich will be able to afford more and better care than the poor.

To what extent do we accept a world where the non-rich die in situations in which the rich would live? To what extent do we hold on to our belief that when it comes to saving lives, medical care should be distributed on the basis of patients' needs, not their wealth? Where and how would we tax the resources to put real weight behind egalitarian principles?

Sharply rising healthcare costs will probably confront governments throughout the developed world with the biggest economic policy issues they will face over the next two generations. The Bush administration has yet to realize this, but other governments are not thinking hard enough, either.

At best, they are seeking ways to keep healthcare spending from rising, as though the genie of medical progress can be forced back into the bottle. Instead, governments should embrace the promise of wonderful innovations in healthcare, and ask how fast spending should rise, and how that rise should be financed.

J. Bradford DeLong is professor of economics at the University of California at Berkeley and was assistant US Treasury secretary during the Clinton presidency.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Yesterday’s recall and referendum votes garnered mixed results for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). All seven of the KMT lawmakers up for a recall survived the vote, and by a convincing margin of, on average, 35 percent agreeing versus 65 percent disagreeing. However, the referendum sponsored by the KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on restarting the operation of the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant in Pingtung County failed. Despite three times more “yes” votes than “no,” voter turnout fell short of the threshold. The nation needs energy stability, especially with the complex international security situation and significant challenges regarding

Most countries are commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II with condemnations of militarism and imperialism, and commemoration of the global catastrophe wrought by the war. On the other hand, China is to hold a military parade. According to China’s state-run Xinhua news agency, Beijing is conducting the military parade in Tiananmen Square on Sept. 3 to “mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II and the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.” However, during World War II, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had not yet been established. It

Much like the first round on July 26, Saturday’s second wave of recall elections — this time targeting seven Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers — also failed. With all 31 KMT legislators who faced recall this summer secure in their posts, the mass recall campaign has come to an end. The outcome was unsurprising. Last month’s across-the-board defeats had already dealt a heavy blow to the morale of recall advocates and the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), while bolstering the confidence of the KMT and its ally the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP). It seemed a foregone conclusion that recalls would falter, as

A recent critique of former British prime minister Boris Johnson’s speech in Taiwan (“Invite ‘will-bes,’ not has-beens,” by Sasha B. Chhabra, Aug. 12, page 8) seriously misinterpreted his remarks, twisting them to fit a preconceived narrative. As a Taiwanese who witnessed his political rise and fall firsthand while living in the UK and was present for his speech in Taipei, I have a unique vantage point from which to say I think the critiques of his visit deliberately misinterpreted his words. By dwelling on his personal controversies, they obscured the real substance of his message. A clarification is needed to