Voting "no" on the EU Constitution would not constitute a French "no" to Europe, as some believe; it would merely be a vote of no confidence in Jacques Chirac's presidency. Anything that diminishes Chirac -- who has weakened the EU by pushing a protectionist, corporate state model for Europe and telling the new smaller members to "shut up" when they disagreed with him -- must be considered good news for Europe and European integration.

So those desiring a stronger integrated EU should be rooting for a French "no," knowing full well that some voting "no" would be doing the right thing for the wrong reasons.

Even before this month's referendum, there have been indications that France's ability to mold the EU to its interests has been waning.

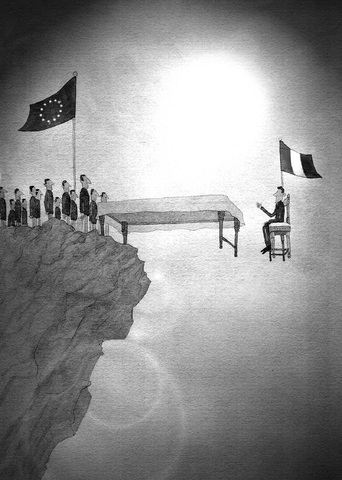

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Just recently, Romanian President Traian Barescu signed the treaty to join the EU. In the period preceding the signing, however, French Foreign Minister Michel Barnier chastised him for lacking a "European reflex." The reason? Barescu plans to align Romania with Anglo-Saxon liberal economic policies, and wants a special relationship with Great Britain and the US to improve security in the Black Sea region. Rather than buckling to France's will, the Romanian president warned French leaders to stop lecturing his country.

This is Europe's future. Even those with close historical ties to France, like Romania, are standing up to France, because Chirac and his colleagues do not offer them the type of "European reflex" they want and need.

The Netherlands -- a traditionally pro-European country -- also may vote "no" on the Constitution in its own referendum (which takes place after the French one) -- not only as a protest against the conservative and moralistic policies of the Balkenende government, but as a rejection of a corporatist Europe dominated by French and German interests.

The corporate state simply has not delivered the goods in continental Europe, and polls are showing voters may take it out on the proposed Constitution.

Certainly the "yes" camp is concerned, with some arguing a French "no" will stall EU enlargement and sink the euro.

"What prospects would there be for constructive talks with Turkey, or progress towards entry of the Balkan states if the French electorate turned its back on the EU?" asks Philip Stephens in the Financial Times. True enough. But a "no" will not mean the French electorate has turned its back on Europe. What's at stake is not enlargement, but whether enlargement takes a more corporatist or market-based form.

Wolfgang Munchau of the Financial Times thinks French rejection of the EU Constitution could sink the euro.

"Without the prospect of eventual political union on the basis of some constitutional treaty," wrote Munchau, "a single currency was always difficult to justify and it might turn out more difficult to sustain ? Without the politics, the euro is "no"t nearly as attractive."

But French rejection of the Constitution does not imply political fragmentation of the EU. If the Constitution is not ratified, the Treaty of Nice becomes the union's operative document. There is no reason whatsoever why the EU should fall into chaos -- and the euro wilt -- now under the Treaty of Nice when it did not do so before.

The truth is that not only will the euro survive a "no" vote; it will prosper. Britain's liberal economic principles are more conducive to European economic growth and prosperity than France's protectionist, corporate-state ones. The market realizes this. With the polls forecasting a "no" vote, the euro remains strong in the currency markets.

Finally, not only will a French "no" serve to marginalize Chirac in Europe, but it will also help undermine the Franco-German alliance that has served France, Germany and Europe so badly in recent years. Europe, in fact, might be on the verge of a major political re-alignment if the French vote "no" and British Prime Minister Tony Blair wins big in the forthcoming UK election. With Chirac down and Blair up, an Anglo Saxon-German alliance might well replace the present Franco-German one. That would be progress indeed.

Melvyn Krauss is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. Copyright: Project Syndicate

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the