Latin America is becoming a rich destination for China in its global quest for energy, with the Chinese quickly signing accords with Venezuela, investing in largely untapped markets like Peru and exploring possibilities in Bolivia and Colombia.

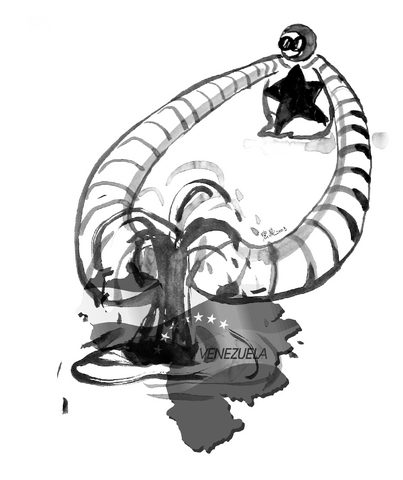

China's sights are focused mostly on Venezuela, which ships more than 60 percent of its crude oil to the United States. With the largest oil reserves outside the Middle East, and a president who says that his country needs to diversify its energy business beyond the United States, Venezuela has emerged as an obvious contender for Beijing's attention.

The Venezuelan leader, Hugo Chavez, accompanied by a delegation of 125 officials and businessmen, and Vice President Zeng Qinghong(曾慶紅) of China signed 19 cooperation agreements in Caracas late in January. They included long-range plans for Chinese stakes in oil and gas fields, most of them now considered marginal but which could become valuable with big investments.

Chavez has been engaged in a war of words with the Bush administration since the White House gave tacit support to a 2002 coup that briefly ousted him. Still, Venezuela is a major source for American oil companies, one of four main providers of imported crude oil to the United States, inexorably linking the two countries' interests.

Analysts and Venezuelan government officials say those ties will not be severed, as Venezuela is a relatively short tanker trip from the US and Venezuelan refineries have been adapted to process the nation's heavy, tarlike crude oil.

"The United States should not be concerned," Rafael Ramirez, Venezuela's energy minister, said in an interview, "because this expansion in no way means that we will be withdrawing from the North American market for political reasons."

In recent months, though, China's voracious economy has brought it to Venezuela, and much of South America, in search of fuel.

"The Chinese are entering without political expectations or demands," said Roger Tissot, an analyst who evaluates political and economic risks in leading oil-producing countries for the PFC Energy Group in Washington. "They just say, 'I'm coming here to invest,' and they can invest billions of dollars. And obviously, as a country with billions to invest, they are taken very seriously."

China's entry is worrisome to some American energy officials, especially because the US is becoming more dependent on foreign oil at a time when foreign reserves remain tight. It was the limited supplies that pushed a barrel of oil to US$55 in October, driving up retail prices and hurting economies. On Monday, crude oil for April delivery settled at US$51.75 in New York, up US$0.26.

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee, headed by Richard Lugar, a Republican, recently asked the government Accountability Office to examine contingency plans should Venezuelan oil stop flowing. Chinese interest in Venezuela, a senior committee aide said, underlines Washington's lack of attention toward Latin America.

"For years and years, the hemisphere has been a low priority for the US, and the Chinese are taking advantage of it," the aide said, speaking on condition of anonymity. "They're taking advantage of the fact that we don't care as much as we should about Latin America."

To be sure, China, the world's second-largest consumer of oil, has emerged as a leading competitor to the US in its search for oil, gas and minerals throughout the world -- notably Central Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

China has accounted for 40 percent of global growth in oil demand in the last four years, according to the US' Energy Department, and its consumption in 20 years is projected to rise to 12.8 million barrels a day from 5.56 million barrels now. Most of that oil will need to be imported. The US now uses 20.4 million barrels a day, nearly 12 million of it imported.

Aggressively seeking out potential deals, China tries to out-muscle the big international oil companies, always beholden to shareholders. Chinese companies, which have substantial government help, can dispense government aid to secure deals, take advantage of lower costs in China and draw on hefty credit lines from the government and Chinese financial institutions.

"These companies tend to make uneconomic bids, use Chinese state bilateral loans and financing, and spend wildly," Frank Verrastro, director and a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, told the Senate Energy Committee early in February.

"Chinese investors pursue market and strategic objectives, rather than commercial ones," he said.

China already operates two oil fields in Venezuela. Under accords signed in Beijing in December and Caracas in January, it would develop 15 declining oil fields in Zumano in eastern Venezuela, buy 120,000 barrels of fuel oil a month and build a plant in Venezuela to produce boiler fuel used in Chinese power plants.

Energy analysts say these deals, though mostly marginal, show that China is willing to wade in slowly, with larger ambitions in mind.

"These are steps you have to take to have a longer-term relationship," said Larry Goldstein, president of the Petroleum Industry Research Foundation in New York. "We don't know enough about whether they will lead to larger projects, but my sense is that they will."

Under the agreements, Venezuela has invited China to participate in much larger projects, like exploring for oil in the Orinoco belt, which has one of the world's great deposits of crude oil, and searching for natural gas offshore through ambitious projects intended to make Venezuela a world competitor in gas.

Analysts note that part of China's effort is to learn about Venezuelan technology, particularly the workings of its heavy-oil refineries. Much of the oil that will be exploited in the future will be tarlike, requiring an intricate and expensive refining process.

In return, China is offering the Venezuelans a US$700 million line of credit to build housing, aid that helps Chavez in his goal of lifting his compatriots out of poverty. The recent trip also yielded plans to invest in telecommunications and farming.

"It's a country that permits you to get more out of agreements than just energy accords," Bernardo Alvarez, Venezuela's ambassador to the US, said of China.

Venezuela, with a view to exports to China, says it is exploring plans to rebuild a Panamanian pipeline to pump crude oil to the Pacific, where it would be loaded onto supertankers that are too big to use the Panama Canal.

Another proposal, with neighboring Colombia, would lead to the construction of a pipeline across Colombia to carry Venezuelan hydrocarbons, which would then be shipped to Asia from Colombia's Pacific ports.

Chavez has promoted these plans in three visits to China. In the most recent, in December, he unveiled a statue of Simon Bolivar in Beijing. Trade between the two countries could rise to US$3 billion this year from US$1.2 billion, Chavez said, celebrating their links as a way for Venezuela to break free of dependence on the American market.

"We have been producing and exporting oil for more than 100 years," Chavez told Chinese businessmen in December. "But these have been 100 years of domination by the United States. Now we are free, and place this oil at the disposal of the great Chinese fatherland."

China, though, is not just interested in Venezuela. Much of Latin America has become crucial to China's need for raw materials and markets, with trade at US$32.85 billion in the first 10 months of last year, about 50 percent more than in 2003. Mining, analysts say, is among China's priorities, whether it is oil in Venezuela, tin in Chile or gas in Bolivia.

Chinese involvement in Latin America is "growing by leaps and bounds," said Eduardo Gamarra, director of the Latin America and Caribbean Center at Florida International University, adding, "It's driven by the need for privileged access to raw material and privileged access to hydrocarbons."

In Brazil, the state-owned Petrobras and China National Offshore Oil have been studying the viability of joint operations in refining, pipelines and exploration in their two countries and in other parts of the world. This comes after a US$1 billion Brazilian agreement with another Chinese company, Sinopec, to build a gas pipeline that will cross Brazil.

In Bolivia, Shengli International Petroleum Development has opened an office in the gas-rich eastern region and announced plans to invest up to US$1.5 billion, though it is awaiting a new hydrocarbons law being drafted before committing itself to deals.

In Ecuador, China National Petroleum and Sinopec have been looking at oil blocks that the government is trying to develop.

In Peru, the Chinese vice president signed a memorandum of understanding in January that could lead to more exploration deals. Currently, a subsidiary of China National Petroleum produces oil.

The Colombian state oil company has been discussing exploration and production with the Chinese. Part of the lure is in new, more beneficial terms for oil companies and an improving security situation.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

After 37 US lawmakers wrote to express concern over legislators’ stalling of critical budgets, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) pledged to make the Executive Yuan’s proposed NT$1.25 trillion (US$39.7 billion) special defense budget a top priority for legislative review. On Tuesday, it was finally listed on the legislator’s plenary agenda for Friday next week. The special defense budget was proposed by President William Lai’s (賴清德) administration in November last year to enhance the nation’s defense capabilities against external threats from China. However, the legislature, dominated by the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), repeatedly blocked its review. The

In her article in Foreign Affairs, “A Perfect Storm for Taiwan in 2026?,” Yun Sun (孫韻), director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said that the US has grown indifferent to Taiwan, contending that, since it has long been the fear of US intervention — and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) inability to prevail against US forces — that has deterred China from using force against Taiwan, this perceived indifference from the US could lead China to conclude that a window of opportunity for a Taiwan invasion has opened this year. Most notably, she observes that

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) said on Monday that it would be announcing its mayoral nominees for New Taipei City, Yilan County and Chiayi City on March 11, after which it would begin talks with the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) to field joint opposition candidates. The KMT would likely support Deputy Taipei Mayor Lee Shu-chuan (李四川) as its candidate for New Taipei City. The TPP is fielding its chairman, Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌), for New Taipei City mayor, after Huang had officially announced his candidacy in December last year. Speaking in a radio program, Huang was asked whether he would join Lee’s