After a dozen years of stagnation, Japan's economy seems to be looking up. But appearances can deceive. Despite improvements and reforms, many of Japan's fundamentals remain woeful.

Japan's decline has been palpable. In the late 1980s, it was fashionable in some Japanese policy circles to argue that the Pax Americana was over, to be replaced in Asia by Pax Japonica. America's economy seemed to be tanking, Japan's was soaring, and projections favored next year as the date when it would overtake the US. That things have turned out far differently reflects Japan's inertia.

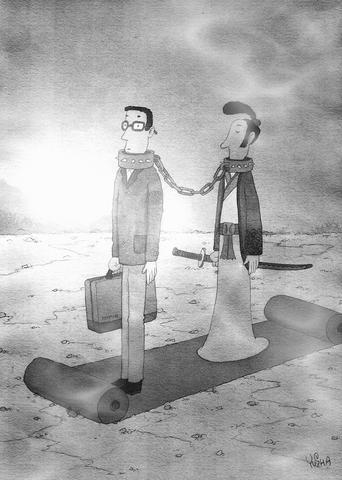

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

The problems underlying Japan's decline are legion. Japanese policymakers and business leaders do not understand the concept of "creative destruction." Too many industrial dinosaurs are kept on life support. So, although some firms do extremely well -- say, Toyota and Canon -- there is little space for new ventures and entrepreneurs. If Japan's economy were a computer, it would have a hard disk full of obsolescent programs and a "delete" button that doesn't work.

No matter what criterion one uses, Japan's economy remains the most closed among Organization for Economic Community Development (OECD) countries and one of the most closed in the world. Not only is foreign capital conspicuously absent, but so are foreign managers, workers, intellectuals, and ideas. Universities, think tanks, and the media are for the most part insular institutions.

Similarly, while non-government organizations (NGOs) are a dynamic component in most societies nowadays, Japan has few, and major international NGOs are nonexistent or have only a weak presence. Oxfam, one of the world's leading NGOs, with offices and branches all over the world, is absent altogether.

The closed nature of Japanese society and the dearth of ideas are partly attributable to the linguistic barrier. Where Japan really falls short is in English -- the global language, and thus the main purveyor of global ideas. In Asia, Japan ranks above only North Korea in scores on the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL).

Moreover, Japan's demographics are among the worst in the world. In this respect, Europe is not much better, although its current restrictive immigration policies will likely be eased over the next decade or so. No such assumption can be made about Japan, where an aging population will intensify the closed and intellectually arid nature of its society.

As a major trading power, Japan should be a leading player in the WTO and in trade forums. Yet despite being one of the main beneficiaries of the post-World War II open and multilateral trading system, Japan stands out as a retrograde mercantilist state.

Isolation has brought confusion about Japan's place in the world. While Japan's government lobbies hard to get a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, its Prime Minister regularly flouts Asian opinion by paying his respects to war criminals at the Yasukuni Shrine. Apart from the immorality of such public behavior (imagine a German chancellor paying his respects at Goebbels' grave!), the fact that both China and the US have veto power at the UN suggests that it is stupid even from the standpoint of Realpolitik.

Indeed, relations with China are Japan's most profound problem. Japan's emergence as East Asia's leading power in the 19th and early 20th centuries involved three brutal wars in China, in which the Japanese army committed dreadful atrocities. The 1949 communist takeover in China, the Cold War, America's adoption of Japan as its pampered protege, and the failure to prosecute Emperor Hirohito for war crimes, allowed Japan to avoid a moral reckoning. Now, as China rises and Japan declines, the old, deep-seated suspicions, tensions, and distrust are resurfacing.

Japan's grim outlook is bad news for the world because it is the globe's second leading economic power. Prospects for Japan acting as a global economic locomotive and of playing a role in poverty reduction and economic development are, for now, almost nil. Indeed, Japan's growth is being driven overwhelmingly by trade with China -- a country with only one-thirtieth of Japan per capita GDP!

From a broader geopolitical perspective, the situation becomes alarming. Despite its frequent economic booms, Asia is also a strategic and security minefield. A sclerotic, atavistic, nationalist, and inward-looking Japan can only aggravate the situation.

What should Japan do? The only solution for Japan is to open up -- not only its economy, but its society, its universities, its media, its think tanks, and, indeed, its bars and bathhouses. Many young Japanese -- often the brightest and most entrepreneurial -- demand to live in an open society, but the option they are choosing now is emigration.

An open Japan would, by definition, be more outward-looking, would speak better English so that it could communicate across Asia and the world, would be more influenced by foreign ideas -- including ideas concerning war guilt. It has been 150 years since the "black ships" of the US Navy forcibly opened up Japan. Today, the Japanese must open up their country themselves.

Jean-Pierre Lehmann is professor of international political economy and founding director of The Evian Group.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmaker Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) on Saturday won the party’s chairperson election with 65,122 votes, or 50.15 percent of the votes, becoming the second woman in the seat and the first to have switched allegiance from the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to the KMT. Cheng, running for the top KMT position for the first time, had been termed a “dark horse,” while the biggest contender was former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), considered by many to represent the party’s establishment elite. Hau also has substantial experience in government and in the KMT. Cheng joined the Wild Lily Student

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) has its chairperson election tomorrow. Although the party has long positioned itself as “China friendly,” the election is overshadowed by “an overwhelming wave of Chinese intervention.” The six candidates vying for the chair are former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), former lawmaker Cheng Li-wen (鄭麗文), Legislator Luo Chih-chiang (羅智強), Sun Yat-sen School president Chang Ya-chung (張亞中), former National Assembly representative Tsai Chih-hong (蔡志弘) and former Changhua County comissioner Zhuo Bo-yuan (卓伯源). While Cheng and Hau are front-runners in different surveys, Hau has complained of an online defamation campaign against him coming from accounts with foreign IP addresses,

When Taiwan High Speed Rail Corp (THSRC) announced the implementation of a new “quiet carriage” policy across all train cars on Sept. 22, I — a classroom teacher who frequently takes the high-speed rail — was filled with anticipation. The days of passengers videoconferencing as if there were no one else on the train, playing videos at full volume or speaking loudly without regard for others finally seemed numbered. However, this battle for silence was lost after less than one month. Faced with emotional guilt from infants and anxious parents, THSRC caved and retreated. However, official high-speed rail data have long

In 1976, the Gang of Four was ousted. The Gang of Four was a leftist political group comprising Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members: Jiang Qing (江青), its leading figure and Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) last wife; Zhang Chunqiao (張春橋); Yao Wenyuan (姚文元); and Wang Hongwen (王洪文). The four wielded supreme power during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), but when Mao died, they were overthrown and charged with crimes against China in what was in essence a political coup of the right against the left. The same type of thing might be happening again as the CCP has expelled nine top generals. Rather than a