Traveling from Berlin to Riga, Latvia's capital, is an eye-opener, because you get to see much of what is going wrong in European integration nowadays, just months before a further 10 states join the EU, bringing it up to 25 from the original six.

In Berlin before I left, German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder had just welcomed his French and British colleagues for an exchange of views on the state and future of the union. They were, the chiefs of the three largest members of the EU declared, only advancing proposals; nothing could be further from their minds than to form a steering group to run the affairs of the enlarged union, even if henceforth they would meet again at more or less regular intervals.

If they really hoped to be believed, they should have listened to my interlocutors in the old city of Riga over the next few days.

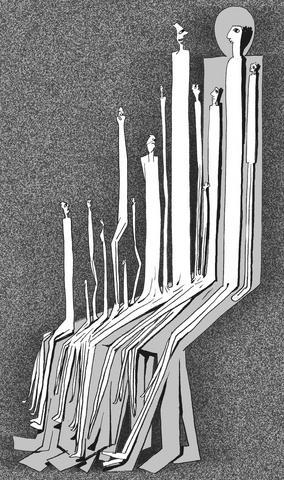

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

The three Baltic countries -- Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania -- will be among the smallest members when they join the union on May 1, their total of 6 million people representing just 1.5 percent of the then EU's population. Yet in marked contrast to the smaller nations that half a century earlier had joined France, Italy and Germany in launching the union's forerunner, the European Economic Community, the new arrivals are digging in their heels, demanding equal rights. Although as small countries they have learnt that the big ones usually get their way, they deeply resented the Berlin meeting because they see in it an attempt to limit their rights in the club they are about to join.

The attitudes of the EU's big and small countries suggest that European integration's basic bargain is no longer regarded as fair. Under that bargain, the bigger states accepted restraints on their power in order to increase the weight of the union as a whole while the smaller ones realized that being part of the club gave them a chance they would not have otherwise, namely to participate in the shaping of common policies. Europe, once the continent of power clashes and balances, became a community of law where big and small follow common rules to reach common decisions.

Now, as Berlin and Riga suggest, power is returning as the trump card. The authority of the big countries derives not from their European credentials but from their power ranking; the resentment of the smaller countries flows not from a different notion of integration but from their fear of losing out. What used to succeed as a win-win arrangement for big and small alike, now appears as a zero-sum game to many of them.

There are explanations for this. In a union of soon 25 members, it will be increasingly difficult to let everyone have a say and to generate consensus. On issues of foreign and security policy, moreover, agreement among the heavyweights of the union is essential for common action.

Unless France, Britain and Germany agree, there is little chance the union can act effectively on the international stage. At the same time, giving up sovereignty for the sake of integration is tough for the new members from Eastern Europe that only a decade ago wrested the right to govern themselves from Soviet control.

Yet big and small alike must realize that their current disposition implies the slow suffocation of Europe's most exciting and successful experiment in bringing peace and prosperity to the old continent. To save it, the bigger ones will indeed have to take the lead. But instead of offering ready solutions for the rest to endorse, leadership will have to consist of working with the other members, patiently and discretely, so that all, or at least most, feel they are involved in formulating common positions.? Only then will the smaller members feel adequately respected. Only then will all members again concentrate on getting things done for all instead of each of them concentrating on getting the most out of it for himself.

There are many who believe that this kind of patient leadership is incompatible with a union of 25. France and Germany, acting together, were able for many years to provide this sort of leadership, and this should be recalled. Whenever they came out with a proposal, the others gave them credit that it was in the interest of the union as a whole; whenever there was a deadlock, the others looked for leadership from Paris and Bonn/Berlin to overcome it.

In the past, German governments rightly took pride in being seen by the smaller members as their best partner, essential for the Franco-German leadership to work. Today, Germany has joined France in neglecting the smaller members for the sake of being recognized as one of the big boys. So the Franco-German couple has lost the credit it once enjoyed. Bringing in Britain is an admission of that fact.

But because Britain remains lukewarm on European integration, the threesome can never serve as the motor for moving Europe forward. Even in an enlarged union, only France and Germany can do that job, provided they make a determined effort to regain the trust of the other, mostly smaller members, old and new. While these expect little from an often indifferent France, they still, as the discussions in Riga suggest, would be disposed to putting their trust in Germany -- if only German governments once again show they care.

Christoph Bertram is director of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin.

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the

The last foreign delegation Nicolas Maduro met before he went to bed Friday night (January 2) was led by China’s top Latin America diplomat. “I had a pleasant meeting with Qiu Xiaoqi (邱小琪), Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping (習近平),” Venezuela’s soon-to-be ex-president tweeted on Telegram, “and we reaffirmed our commitment to the strategic relationship that is progressing and strengthening in various areas for building a multipolar world of development and peace.” Judging by how minutely the Central Intelligence Agency was monitoring Maduro’s every move on Friday, President Trump himself was certainly aware of Maduro’s felicitations to his Chinese guest. Just

A recent piece of international news has drawn surprisingly little attention, yet it deserves far closer scrutiny. German industrial heavyweight Siemens Mobility has reportedly outmaneuvered long-entrenched Chinese competitors in Southeast Asian infrastructure to secure a strategic partnership with Vietnam’s largest private conglomerate, Vingroup. The agreement positions Siemens to participate in the construction of a high-speed rail link between Hanoi and Ha Long Bay. German media were blunt in their assessment: This was not merely a commercial win, but has symbolic significance in “reshaping geopolitical influence.” At first glance, this might look like a routine outcome of corporate bidding. However, placed in

China often describes itself as the natural leader of the global south: a power that respects sovereignty, rejects coercion and offers developing countries an alternative to Western pressure. For years, Venezuela was held up — implicitly and sometimes explicitly — as proof that this model worked. Today, Venezuela is exposing the limits of that claim. Beijing’s response to the latest crisis in Venezuela has been striking not only for its content, but for its tone. Chinese officials have abandoned their usual restrained diplomatic phrasing and adopted language that is unusually direct by Beijing’s standards. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs described the