Farmer Loi Bangoti picks corn on the lush, cool slopes of his land, nestled under the cloudy shadow of Africa's highest mountains.

Half a world away, farmer Tim Recker drives his combine through the famously flat, open corn fields that stretch out in the sun across the plains of Iowa.

For all their differences, both men rely on a complex global food market that decides how much their corn is worth and who will buy it. And the lives of both -- along with millions of other farmers -- will be affected by a growing movement to change one of the biggest forces shaping the market: Subsidies.

PHOTO: AP

Many experts agree that farmers need help to grow food year in and year out, but Western farmers may get too much and African farmers too little. Western farmers receive billions of dollars in subsidies every year, which makes their food cheap to grow and sell. However, African farmers are left on their own because of decades of anti-subsidy policies pushed by the World Bank and others as a condition for aid money.

Now Africans are fighting back.

Some African countries are considering subsidies for their own farmers -- Malawi has started providing discount vouchers for seed and fertilizer to farmers, and is seeing such a bumper crop that it now sends emergency corn to neighboring Zimbabwe. African countries have also joined in lawsuits opposing US subsidies, resulting in a WTO ruling in October that the US could face billions of dollars in sanctions.

SCRUTINY

At the same time, subsidies are facing more scrutiny than ever within the US. A farm bill before Congress -- the first in five years -- was once a shoo-in, but now faces the threat of a veto from US President George W. Bush. He has called for an end to farm subsidies by 2010 to avoid trade conflicts.

The complexities of the subsidy debate play out far from the courts and the chambers of power in the daily lives of farmers like Bangoti and Recker.

Bangoti's story shows how a little help can go a long way. He points with pride to his three-quarter hectare plot of corn, beans and potatoes, stretching up the slopes of Mount Meru in a mosaic of various greens dotted with the brown of a few fallow fields.

Back in 1992, Bangoti lived in a mud hut, worked as a day laborer, herded skinny cows and harvested barely enough corn and beans to feed his family. Then scientists came to his farm as part of an agricultural aid program.

They looked at his soil, found the right seed and gave him his first batch of chemical fertilizer. They showed him how to get as much milk from two dairy cows as from his 20 traditional cattle. The techniques were simple, yet rare in Africa, where few labs analyze soil samples and few companies develop improved seed.

By 1993, Bangoti had tripled his output -- and profits. At the time, he was profiled in an Associated Press story on African farming. His success since proves it was no accident: He is still farming, and still thriving.

"I built my own modern house," Bangoti, 50, said proudly, sitting under a shiny tin roof surrounded by dark blue concrete walls. ``I was able to send my children to school. ... A long time ago, you could have a lot of cows, and have nothing. Now, with this modern way of living, you can have a few cows, but produce more.''

Bangoti said all it would take is a little training and a few supplies for Africans to grow all the food they need.

They once did, in the 1960s. Now, Africans import 25 percent of what they eat. Their share of the global agricultural market is down from 8 percent to 2 percent. And theirs is the only continent where food production per capita has fallen -- roughly 22 percent since 1967, according to the World Resource Institute.

One reason, experts say, is the loss of subsidies. In exchange for foreign aid, debt-saddled African countries agreed to cut subsidies. Less than 4 percent of government spending in sub-Saharan Africa now goes to agriculture.

But without a safety net, a single bad season can bankrupt a farmer, and often does. And without help, African farmers are too poor to pay for the good seed and fertilizer that bring land to life.

REFORM

There are signs of change. The World Bank is rethinking its stance on subsidies after a scathing internal review last month, and it made agriculture the center of its agenda this year for the first time in more than two decades. About 70 percent of Africans live off the land, and agricultural reform -- from seed to market -- is the surest way to lift the continent out of poverty.

African governments have promised to double their spending on agriculture. And the Gates Foundation and former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan are leading an effort to bring to Africa the green revolution that swept through Asia.

As Bangoti leafs through a photo album of the experts who have visited his farm, he said the training and the aid have changed his life.

"Now I am always moving forward. I never go backward," he said.

Bangoti said he could grow even more -- if he could sell it. But he is competing against farmers in the richest countries of the world who get a lot more help, such as Recker.

The corn fields Recker sees through the glass patio doors of his modest ranch house have supported his family for generations. Recker followed his father and grandfather into farming, and works 585 hectares in northeastern Iowa with his brother.

Today, the price of corn is at a record high because it is in demand to make ethanol. Recker's business revolves around the timing of the markets as much as the seasons. As he sits at his breakfast table in his overalls and baseball cap, his mobile phone beeps to announce the arrival of the opening commodity prices at his local mill.

It was a different story when Recker started out in the mid-1980s, during one of the country's worst agricultural crises. He says he could never have survived it without subsidies.

Subsidies kick in when prices are low. But they are given for each bushel, which creates the incentive for farmers to grow as many bushels as they can. The torrent of food then drives down prices and makes it next to impossible for African farmers to compete.

Some of the extra food ends up in Africa. Most Iowa corn floats down the Mississippi River on barges to become feed for livestock or grist for ethanol. But at some point Recker's corn has almost certainly gone to Africa for food relief, which experts say destroys local markets.

LARGEST DONOR

The US -- the largest donor to the UN World Food program -- sends Africa corn, wheat, sorghum and soy beans. Aid agencies then have to hand out free or cheap US food instead of buying from African farmers. The cheap imported grain keeps Africans poor, and therefore dependent on cheap imported grain.

The crisis is such that Atlanta-based CARE International, one of the world's largest charities, announced in August it would walk away from US$45 million in US food to avoid disrupting the economies of the people it wants to help.

The subsidy system also makes it harder for African farmers to compete on the world market. Western farmers get 29 percent of their income on average from their governments, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development said. So they can sell their food for far less than Africans who get nothing.

African farmers may get help from an unexpected source -- US corn and wheat farmers.

A new generation of corn and wheat farmers is arguing that the current subsidy system no longer meets the needs of their rapidly changing industries. Instead of subsidies per bushel, they want the guarantee of a minimum level of revenue for each farm.

The change seems small, but it could result in farmers growing far less -- and dumping far less extra corn and wheat on global markets.

Back in Tanzania, Bangoti is not waiting for the outcome of the subsidy debate. In fact, he has never heard of subsidies for Western farmers, and he has no idea how they might affect his business.

LONG FLIGHT: The jets would be flown by US pilots, with Taiwanese copilots in the two-seat F-16D variant to help familiarize them with the aircraft, the source said The US is expected to fly 10 Lockheed Martin F-16C/D Block 70/72 jets to Taiwan over the coming months to fulfill a long-awaited order of 66 aircraft, a defense official said yesterday. Word that the first batch of the jets would be delivered soon was welcome news to Taiwan, which has become concerned about delays in the delivery of US arms amid rising military tensions with China. Speaking on condition of anonymity, the official said the initial tranche of the nation’s F-16s are rolling off assembly lines in the US and would be flown under their own power to Taiwan by way

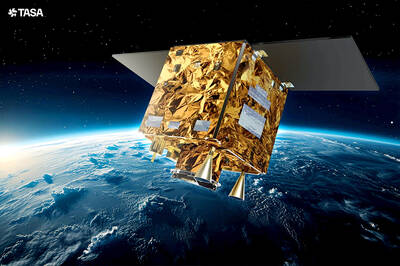

OBJECTS AT SEA: Satellites with synthetic-aperture radar could aid in the detection of small Chinese boats attempting to illegally enter Taiwan, the space agency head said Taiwan aims to send the nation’s first low Earth orbit (LEO) satellite into space in 2027, while the first Formosat-8 and Formosat-9 spacecraft are to be launched in October and 2028 respectively, the National Science and Technology Council said yesterday. The council laid out its space development plan in a report reviewed by members of the legislature’s Education and Culture Committee. Six LEO satellites would be produced in the initial phase, with the first one, the B5G-1A, scheduled to be launched in 2027, the council said in the report. Regarding the second satellite, the B5G-1B, the government plans to work with private contractors

‘OF COURSE A COUNTRY’: The president outlined that Taiwan has all the necessary features of a nation, including citizens, land, government and sovereignty President William Lai (賴清德) discussed the meaning of “nation” during a speech in New Taipei City last night, emphasizing that Taiwan is a country as he condemned China’s misinterpretation of UN Resolution 2758. The speech was the first in a series of 10 that Lai is scheduled to give across Taiwan. It is the responsibility of Taiwanese citizens to stand united to defend their national sovereignty, democracy, liberty, way of life and the future of the next generation, Lai said. This is the most important legacy the people of this era could pass on to future generations, he said. Lai went on to discuss

MISSION: The Indo-Pacific region is ‘the priority theater,’ where the task of deterrence extends across the entire region, including Taiwan, the US Pacific Fleet commander said The US Navy’s “mission of deterrence” in the Indo-Pacific theater applies to Taiwan, Pacific Fleet Commander Admiral Stephen Koehler told the South China Sea Conference on Tuesday. The conference, organized by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), is an international platform for senior officials and experts from countries with security interests in the region. “The Pacific Fleet’s mission is to deter aggression across the Western Pacific, together with our allies and partners, and to prevail in combat if necessary, Koehler said in the event’s keynote speech. “That mission of deterrence applies regionwide — including the South China Sea and Taiwan,” he