A new method of communicating is creating intriguing services that beat old ways of sending information. But law enforcement makes a somber claim: These new networks will become a boon to criminals and terrorists unless the government can easily listen in.

This was the story line in the mid-1990s when then US president Bill Clinton's administration sought to have electronic communications encrypted only by a National Security Agency-developed "Clipper Chip," for which the feds would have a key.

The Clipper Chip eventually went the way of clipper ships after industry balked and researchers showed its cryptographic approach was flawed anyway. But while the Clipper Chip died, the dilemma it illuminated remains.

With each new advance in communications, the government wants the same level of snooping power that authorities have exercised over phone conversations for a century. Technologists recoil, accusing the government of micromanaging -- and potentially limiting -- innovation.

Today, this tug of war is playing out over the Federal Communications Commission's demands that a phone-wiretapping law be extended to voice-over-Internet services and broadband networks.

Opponents are trying to block the ruling on various grounds: that it goes beyond the original scope of the law, that it will force network owners to make complicated changes at their own expense, or that it will have questionable value in improving security.

No matter who wins the battle over this law -- the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act, known as CALEA -- this probably won't be the last time authorities raise hackles by seeking a bird's eye view over the freewheeling information flow created by new technology.

Authorities are justified in trying to reduce the ways that technology helps dangerous people operate in the shadows, said Daniel Solove, author of The Digital Person.

But a parallel concern is that technology can end up increasing the government's surveillance power rather than just maintaining it.

"We have to ask ourselves anew the larger question: What surveillance power should the government have?" said Solove, an assistant professor at George Washington University Law School. "And to what extent should the government be allowed to manage the development of technology to embody its surveillance capability?"

Wiretapping -- so named because eavesdropping police placed metal clips on the analog wires that carried conversations -- has a complex legal history. A 1928 case, Olmstead v. United States, legitimized the practice, when the Supreme Court ruled it was acceptable for police to monitor the private calls of a suspected bootlegger. Behind that 5-4 ruling, however, a seminal debate was raging. The dissenting opinion by Justice Louis Brandeis argued, among other things, that the government had no right to open someone's mail, so why should a phone -- or other technologies that might emerge -- carry different expectations about privacy?

In 1967, as the dawn of the digital age was fulfilling Brandeis' fears that other forms of technological eavesdropping would become possible, the Supreme Court reversed Olmstead. After that, authorities had to get a search warrant before setting wiretaps, even on payphones.

That apparently hasn't been much of a hindrance. State and federal authorities have had 30,975 wiretap requests authorized since 1968, with only 30 rejections, according to the Electronic Privacy Information Center. Some 1,710 wiretaps were authorized last year, the most ever, with zero denied.

Since 1980, authorities also have been able to set secret wiretaps with the approval of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which privacy watchdogs say requires a lower standard of evidence than the general warrant process. For the first two decades FISA orders numbered less than 1,000 annually; 2003 and 2004 each saw more than 1,700. Only four FISA applications have been rejected, all in 2003.

But technology began to pose obstacles in the 1980s. Suddenly some wiretaps had to become virtual, using "packet sniffing" programs that spy on the splintered packets of data that make up network traffic.

Congress passed CALEA in 1994, requiring telecom carriers to ensure that their networks left it relatively easy for law enforcement to set wiretaps. The law applied to landline and cell phone networks but essentially exempted the Internet.

The FBI also was developing Carnivore, a program that agents could tailor to grab specific e-mails and other Internet communications defined in a court order.

And all the while the NSA was harvesting the fruits of a system called Echelon, intercepting millions of international telephone calls and feeding them into the agency's humungous maw for analysis.

DEFENDING DEMOCRACY: Taiwan shares the same values as those that fought in WWII, and nations must unite to halt the expansion of a new authoritarian bloc, Lai said The government yesterday held a commemoration ceremony for Victory in Europe (V-E) Day, joining the rest of the world for the first time to mark the anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe. Taiwan honoring V-E Day signifies “our growing connections with the international community,” President William Lai (賴清德) said at a reception in Taipei on the 80th anniversary of V-E Day. One of the major lessons of World War II is that “authoritarianism and aggression lead only to slaughter, tragedy and greater inequality,” Lai said. Even more importantly, the war also taught people that “those who cherish peace cannot

STEADFAST FRIEND: The bills encourage increased Taiwan-US engagement and address China’s distortion of UN Resolution 2758 to isolate Taiwan internationally The Presidential Office yesterday thanked the US House of Representatives for unanimously passing two Taiwan-related bills highlighting its solid support for Taiwan’s democracy and global participation, and for deepening bilateral relations. One of the bills, the Taiwan Assurance Implementation Act, requires the US Department of State to periodically review its guidelines for engagement with Taiwan, and report to the US Congress on the guidelines and plans to lift self-imposed limitations on US-Taiwan engagement. The other bill is the Taiwan International Solidarity Act, which clarifies that UN Resolution 2758 does not address the issue of the representation of Taiwan or its people in

US Indo-Pacific Commander Admiral Samuel Paparo on Friday expressed concern over the rate at which China is diversifying its military exercises, the Financial Times (FT) reported on Saturday. “The rates of change on the depth and breadth of their exercises is the one non-linear effect that I’ve seen in the last year that wakes me up at night or keeps me up at night,” Paparo was quoted by FT as saying while attending the annual Sedona Forum at the McCain Institute in Arizona. Paparo also expressed concern over the speed with which China was expanding its military. While the US

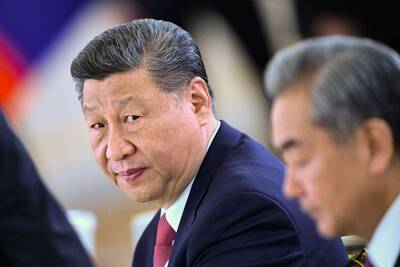

‘FALLACY’: Xi’s assertions that Taiwan was given to the PRC after WWII confused right and wrong, and were contrary to the facts, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said The Ministry of Foreign Affairs yesterday called Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) claim that China historically has sovereignty over Taiwan “deceptive” and “contrary to the facts.” In an article published on Wednesday in the Russian state-run Rossiyskaya Gazeta, Xi said that this year not only marks 80 years since the end of World War II and the founding of the UN, but also “Taiwan’s restoration to China.” “A series of instruments with legal effect under international law, including the Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Declaration have affirmed China’s sovereignty over Taiwan,” Xi wrote. “The historical and legal fact” of these documents, as well