Thirteen-year-old Sanjay Chhetri has a recurring fear: that one day, the dark, dank mine where he works will cave in and bury him alive.

Like thousands of children in India’s remote northeast, Chhetri begins work in the middle of the night, ready to dig pits, squat through narrow tunnels and cut coal shards.

At 1.37m, the skinny teenager is the perfect fit for a job in the lucrative mining industry in Meghalaya state, whose crudely built rat-hole mines are too small for most adults to enter.

Photo: AFP

Each day Sanjay makes his way down a series of slippery ladders in the pitch-dark, carrying two pickaxes, with a tiny flashlight strapped to his head.

Seven months into the job, he still walks gingerly, taking care not to miss a step and fall 50m.

Once he reaches the bottom, he squats as low as he can and slips into the 60cm high rat-hole, pulling an empty wagon behind him.

That’s where his nightmares begin.

“It’s terrifying to imagine the roof falling on me when I am working,” he said.

Twelve hours later, he will have earned 200 rupees (US$4) for a day’s work, more than his parents make as laborers in the state capital Shillong.

The eldest boy in a family of 10, Sanjay left school two years ago when his family could no longer pay the bills.

“It’s very difficult work. I struggle to pull that wagon once I have filled it with coal,” he said.

As he shivers in coal-stained jeans and flip-flops — revealing wrinkled feet that look like they belong to a much older man — he says his parents constantly ask him to return home to work with them.

However, he is not ready to leave the mines yet.

“I need to save money so I can return to school. I miss my friends and I still remember school. I still have my old dreams,” he said.

Mine manager Kumar Subba says children like Sanjay turn up in droves outside Meghalaya’s coal mines, asking for work.

“New kids are always showing up here. And they lie about their age, telling you they are 20 years old when you can see from their faces that they are much, much younger,” he said.

Baby-faced Surya Limu is among the most recent recruits to join Subba’s team in Rymbai Village.

Limu, who claims he is 17, left his native Nepal for Meghalaya when his father died in a house fire, leaving behind a widow and two children. Unlike his more experienced colleagues, Limu moves slowly down the precarious mine steps, his delicate features straining with the effort.

“Of course I feel scared but what can I do? I need money, how else can I stay alive?” he said.

Child labor is officially illegal in India, with several state laws making the employment of anyone under 18 in a hazardous industry a non-bailable offense.

Furthermore, India’s 1952 Mines Act prohibits coal companies from hiring anyone under 18 to work inside a mine.

However, Meghalaya has traditionally been exempt due to its special status as a northeastern state with a significant tribal population.

This means that in certain sectors like mining, customary laws overrule national regulations. Any land owner can dig for coal in the state, and prevailing laws do not require them to put any safety measures in place.

Shillong-based non-profit Impulse NGO Network says about 70,000 children are currently employed in Meghalaya’s mines, with several thousand more working at coal depots.

“The mine owners find it cheaper to extract coal using these crude, unscientific methods and they find it cheaper to hire children. And the police take bribes to look the other way,” Impulse activitst Rosanna Lyngdoh said.

After decades of unregulated mining, the state is due to enforce its first-ever mining policy later this year. The draft legislation instructs mine owners not to employ children, but it does allow rat-hole mining to continue.

“As long as they allow rat-hole mining, children will always be employed in these mines, because they are small enough to crawl inside,” Lyngdoh said.

Accidents and quiet burials are commonplace, with years of uncontrolled drilling making the rat-holes unstable and liable to collapse at any moment.

Gopal Rai, who lives with seven other miners in a 2.5m by 3m tarpaulin-covered bamboo and metal shack, compensation is rarely, if ever, paid to injured children.

In Italy’s storied gold-making hubs, jewelers are reworking their designs to trim gold content as they race to blunt the effect of record prices and appeal to shoppers watching their budgets. Gold prices hit a record high on Thursday, surging near US$5,600 an ounce, more than double a year ago as geopolitical concerns and jitters over trade pushed investors toward the safe-haven asset. The rally is putting undue pressure on small artisans as they face mounting demands from customers, including international brands, to produce cheaper items, from signature pieces to wedding rings, according to interviews with four independent jewelers in Italy’s main

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has talked up the benefits of a weaker yen in a campaign speech, adopting a tone at odds with her finance ministry, which has refused to rule out any options to counter excessive foreign exchange volatility. Takaichi later softened her stance, saying she did not have a preference for the yen’s direction. “People say the weak yen is bad right now, but for export industries, it’s a major opportunity,” Takaichi said on Saturday at a rally for Liberal Democratic Party candidate Daishiro Yamagiwa in Kanagawa Prefecture ahead of a snap election on Sunday. “Whether it’s selling food or

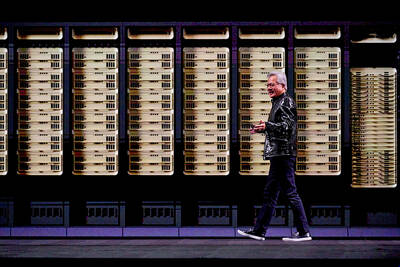

CONCERNS: Tech companies investing in AI businesses that purchase their products have raised questions among investors that they are artificially propping up demand Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Saturday said that the company would be participating in OpenAI’s latest funding round, describing it as potentially “the largest investment we’ve ever made.” “We will invest a great deal of money,” Huang told reporters while visiting Taipei. “I believe in OpenAI. The work that they do is incredible. They’re one of the most consequential companies of our time.” Huang did not say exactly how much Nvidia might contribute, but described the investment as “huge.” “Let Sam announce how much he’s going to raise — it’s for him to decide,” Huang said, referring to OpenAI

The global server market is expected to grow 12.8 percent annually this year, with artificial intelligence (AI) servers projected to account for 16.5 percent, driven by continued investment in AI infrastructure by major cloud service providers (CSPs), market researcher TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. Global AI server shipments this year are expected to increase 28 percent year-on-year to more than 2.7 million units, driven by sustained demand from CSPs and government sovereign cloud projects, TrendForce analyst Frank Kung (龔明德) told the Taipei Times. Demand for GPU-based AI servers, including Nvidia Corp’s GB and Vera Rubin rack systems, is expected to remain high,