Jonathan Abrams was in a spot. He could take the safe bet and accept the US$30 million that Google was offering him for Friendster, the social networking Web start-up he began only a year earlier, in 2002.

Saying yes to Google would provide a quick and stunning payout for relatively little work and instantly place the Friendster Web site in front of hundreds of millions of users across the globe.

But at the same time, some of the biggest names in Silicon Valley were lobbying Abrams, a computer programmer, to reject Google's offer. America Online had offered the two founders of Yahoo a few million dollars each in the mid-1990s for their Web site -- and both became billionaires because they said no.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Sell us a stake in your company for US$13 million, the advisers told Abrams, and we will help build Friendster into an online powerhouse worth hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars.

Abrams spurned Google's advances and charted his own course. In retrospect, he should have taken the US$30 million. If Google had paid him in stock, Abrams would easily be worth US$1 billion today, one person close to Google said.

Friendster essentially created the social networking sector three years ago by offering users a site where they could browse profiles posted by friends and the friends of friends in search of dates and playmates. But so badly did Friendster fumble its early lead that, as of last month, it ranked 14th among social networking sites tracked by comScore Media Metrix.

Why and how Friendster missed the mark is a salutary Silicon Valley tale so instructive that Mikolaj Jan Piskorski, an assistant professor at the Harvard Business School, uses the company's inglorious fall as a case study in his strategy classes.

`an ego story'

There is no single reason that explains Friendster's failures, Piskorski said which is what makes it academic fodder. "It's a power story," he said. "It's a status story. It's an ego story." But largely, he said, Friendster is a "very Silicon Valley story that tells us a lot about how the Valley operates."

The second half of the 1990s had seen any number of failed social networking sites, including forgotten enterprises like Six Degrees and SocialNet.

"We all basically hit the market several years before the market was ready for social networking," said Reid Hoffman, the founding chief executive of SocialNet and an early investor in Friendster.

Abrams, though, had perfect timing. Friendster made its Web debut in March 2003, and though it was then a speck of a start-up that spent no money on marketing, it signed up 3 million registered users by the fall.

The list of venture capitalists enticing him to say no to Google and to go it alone included John Doerr, the legendary venture capitalist at Kleiner Perkins whose list of greatest hits includes Google, Netscape and Amazon.com, and Bob Kagle, the Benchmark Capital partner who first spotted eBay.

Doerr and Kagle took seats on Friendster's board, as did another investor, Timothy Koogle, who had been the chief executive of Yahoo through the second half of the 1990s. Other investors included Peter Thiel, a co-founder of PayPal, which eBay bought for US$1.5 billion in 2002, and K. Ram Shriram, one of the first investors in Google and perhaps the most-sought-after angel investor in Silicon Valley.

Abrams now casts that board, composed primarily of men in their 50s who were far older than the site's target demographic, and the recruits they drafted as the main cause of Friendster's great stumble.

Through a colleague from a previous tech start-up, Melissa Gilbert, Abrams declined to comment for this article, saying he was too busy working on a new start-up to talk about the past. Gilbert, though, who described herself as the first investor in Friendster, echoed the comments of others close to Abrams.

He believed that he had developed a sound business plan for building Friendster into an Internet powerhouse and that the plan foundered when his well-known investors shoved him aside and proceeded to mess everything up, Gilbert wrote in an e-mail message.

Russel Siegelman, one of Doerr's partners at Kleiner Perkins, said Abrams has a point as the original board had little feel for the product.

replaced

But he also described Abrams as a founder in way over his head, which is why, in April 2004, only a few months after investing in the company, the board replaced him as chief executive.

The board lost sight of the task at hand, said Kent Lindstrom, an early investor in Friendster and one of its first employees. As Friendster became more popular, its overwhelmed Web site became slower. Things would become so bad that a Friendster Web page took as long as 40 seconds to download.

Yet, from where Lindstrom sat, technical difficulties proved too pedestrian for a board of this pedigree.

In retrospect, Lindstrom said, the company needed to devote all of its resources to fixing its technological problems. But such are the appetites of companies fixated on growing into multibillion-dollar behemoths. They seek to run even before they can walk.

The board replaced Abrams with one of its own, Koogle, the former chief executive of Yahoo. But Koogle served for only three months.

The board next chose a television industry executive, Scott Sassa, to replace Koogle. That selection might have made sense if the company had been in position to start cutting big advertising deals. But it was not, given that its Web site was not up to speed.

Sassa left after less than a year, which was nearly twice the tenure of his successor, Taek Kwon, who left at the end of last year, six months after he started.

Last fall, Friendster hired an investment banker to shop the company around. In part, the board was inspired by the US$580 million that Rupert Murdoch's News Corp agreed in July last year to pay for Intermix Media and its primary asset, MySpace. In the end, though, the investors failed to find a suitor willing to pay even US$20 million for the company.

Friendster was nearly out of cash by the end of last year. It had halved its payroll, to 25 employees, and advertising was hard to come by on a site that still did not work right. The venture capitalists considered shutting down the company.

obligation

But a sense of obligation and economics prompted Kleiner Perkins, Benchmark and some of the private investors to sink an additional US$3 million into the company at the start of this year.

The venture capitalists reconstructed the board and put Lindstrom, who had been with the company since mid-2003, in charge. The company hired yet another chief of engineering, who laid down the law: At least 80 percent of his people would work on performance and stability issues until the Web site worked as well as it should.

"In the past, we had often chosen the more exotic solution over the more simple solution," Lindstrom said. Trailblazing a new field like social networking was enough of a challenge. "But we were also trying to innovate on the tech side as well," he said. The company finally licked its performance problems this last summer, Lindstrom said.

The team now running Friendster hopes it can position the company as a site for an older demographic group -- people 25 to 40 -- who do not have the time or inclination to spend hours each day on MySpace.

"Friendster missed the chance to become a multibillion-dollar company," said Thiel, the PayPal co-founder who has continued to invest in Friendster. "But I still see a lot of opportunity here."

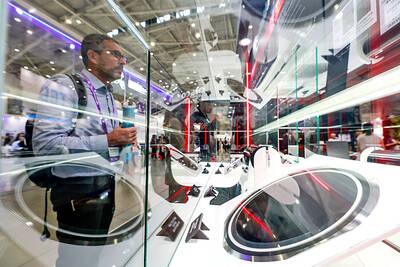

POWERING UP: PSUs for AI servers made up about 50% of Delta’s total server PSU revenue during the first three quarters of last year, the company said Power supply and electronic components maker Delta Electronics Inc (台達電) reported record-high revenue of NT$161.61 billion (US$5.11 billion) for last quarter and said it remains positive about this quarter. Last quarter’s figure was up 7.6 percent from the previous quarter and 41.51 percent higher than a year earlier, and largely in line with Yuanta Securities Investment Consulting Co’s (元大投顧) forecast of NT$160 billion. Delta’s annual revenue last year rose 31.76 percent year-on-year to NT$554.89 billion, also a record high for the company. Its strong performance reflected continued demand for high-performance power solutions and advanced liquid-cooling products used in artificial intelligence (AI) data centers,

SIZE MATTERS: TSMC started phasing out 8-inch wafer production last year, while Samsung is more aggressively retiring 8-inch capacity, TrendForce said Chipmakers are expected to raise prices of 8-inch wafers by up to 20 percent this year on concern over supply constraints as major contract chipmakers Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) and Samsung Electronics Co gradually retire less advanced wafer capacity, TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. It is the first significant across-the-board price hike since a global semiconductor correction in 2023, the Taipei-based market researcher said in a report. Global 8-inch wafer capacity slid 0.3 percent year-on-year last year, although 8-inch wafer prices still hovered at relatively stable levels throughout the year, TrendForce said. The downward trend is expected to continue this year,

A proposed billionaires’ tax in California has ignited a political uproar in Silicon Valley, with tech titans threatening to leave the state while California Governor Gavin Newsom of the Democratic Party maneuvers to defeat a levy that he fears would lead to an exodus of wealth. A technology mecca, California has more billionaires than any other US state — a few hundred, by some estimates. About half its personal income tax revenue, a financial backbone in the nearly US$350 billion budget, comes from the top 1 percent of earners. A large healthcare union is attempting to place a proposal before

Vincent Wei led fellow Singaporean farmers around an empty Malaysian plot, laying out plans for a greenhouse and rows of leafy vegetables. What he pitched was not just space for crops, but a lifeline for growers struggling to make ends meet in a city-state with high prices and little vacant land. The future agriculture hub is part of a joint special economic zone launched last year by the two neighbors, expected to cost US$123 million and produce 10,000 tonnes of fresh produce annually. It is attracting Singaporean farmers with promises of cheaper land, labor and energy just over the border.