There are no more Chiquita company pool parties and barbecues in the gated American Zone of this northern Honduras city. In fact, there are no more Americans.

The crippling strikes are gone, and the regional railroad that once moved bananas and workers is choked with weeds. The fruit pickers are looking for new work, trying to get into the US.

PHOTO: AP

Central America is bidding farewell to the economy that bananas built. Stung by global competition, the US industry that gave rise to "banana republics" and profoundly altered life here has pulled back -- for better or worse.

Industry's boom and bust

For nearly a century, US companies razed jungle for plantations that provided jobs, homes and schools for thousands in Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras and Panama. Along the way, they were accused of paying slave wages, poisoning workers with pesticides and propping up corrupt regimes.

But a protracted trade war between the US and Europe hurt the industry's ability to compete. Ecuador, a low-cost producer, came from nowhere in the 1990s to replace Costa Rica as the world's No. 1 banana grower. A deadly hurricane in 1998 washed away thousands of plantation acres in Honduras. Only half were replanted.

The industry and its allies hope for a comeback. They got their first good news in years with an agreement to slowly reopen the European market to Latin American bananas starting July 1.

But that may not be enough to help the industry recover.

"It came really late," says Manuel Rodriguez, a vice president for Chiquita Brands International Inc "We've been nine years suffering these restrictions."

Formerly United Fruit Co, Chiquita -- literally "little one" in Spanish -- was just the opposite of that for most of the 20th century in Central America.

Its past included ownership of much of the region's fertile land, and accusations of spraying workers with the pesticide nemagon, which the US government banned in 1977 after it was shown to cause sterility, blindness and cancer in humans.

In 1993, more than 16,000 banana plantation workers from Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and the Philippines filed a class-action lawsuit in Texas against US fruit and chemical companies for alleged illnesses as a result of exposure to chemicals.

The companies, including Chiquita, Dole and Del Monte, agreed to pay a total of US$41.5 million in 1997 to those who proved they were sterile.

A similar lawsuit filed by 4,000 Nicaraguan workers is pending in Managua.

Chiquita -- whose Central American headquarters, hospital and executive housing once dominated La Tela -- is no longer the power it was. Most American executives are in the US, and the luxurious beachfront Chiquita resort where they once stayed has been turned into a hotel.

Struck by a hurricane

The largest grower of bananas in Central America, Chiquita is struggling to rebound. The Cincinnati-based company restructured its debt to avoid bankruptcy after losing US$1.5 billion to European Union tariffs that favored former colonies in the Caribbean and Africa over Latin American growers.

Before the restrictions began in 1993, the market for Latin American bananas was growing by up to 14 percent a year in Europe, compared to largely stagnant demand in the US.

Chiquita also spent US$75 million to rebuild after Hurricane Mitch washed away packing plants and banana trees throughout Honduras and parts of Guatemala in 1998. The company's stock price has fallen from US$50 per share in 1991 to less than US$2 now.

Unions and watchdog groups worry that companies like Chiquita will move their operations to Ecuador or even Brazil, both of which are free of the relatively high wages and benefits that years of strikes in Central America have earned.

Most plantations in Ecuador are owned by Noboa Corp, an Ecuadoran conglomerate that sells the Bonita brand. Ecuador has virtually no unions and no worker benefits and wages are half the average US$6 a day in Central America. The cost edge allowed the country to nearly double production from 1990 to 2000, compared to a 15 percent rise in Central America.

Ambigious social awareness

Chiquita says it buys bananas from Ecuador only when there are shortages in Central America, preferring suppliers that meet the company's social and environmental standards -- part of a recent Chiquita campaign to support fair working conditions and attract socially aware consumers.

But Chiquita's level of caring is disputed.

After Mitch, the company replanted only half its plantations in Honduras, deciding to grow and harvest bananas closer together. The new system produced nearly the same amount, but cost thousands of jobs as Central American producers shed 30 percent of their work force, according to union members. Remaining workers complain they work harder for the same pay and less benefits such as health coverage.

Late in June, Chiquita announced it was closing a banana plantation in western Panama and shifting 550 workers to other sites. Workers in Panama have staged work stoppages to demand that jobs be restored, and watchdog groups complain that companies are buying from more independent producers in southern Guatemala, where work conditions and pay are similar to those in Ecuador.

In Honduras, the plantations are among the only options for uneducated workers. Those who are still young can find jobs in the growing number of "maquila," or assembly-for-export, factories. But those jobs often don't pay as much as work on unionized banana plantations, where housing and schools are often provided.

Many people are heading north.

Racing to keep pace with hundreds of green bananas rolling by on a conveyer belt, Elba Brizucla slides blue-and-white Chiquita stickers on each bunch as "Stayin' Alive" blares from a radio behind her. She plans to sneak into the US and work at her son's North Carolina restaurant cooking fried chicken -- one of Honduras' most popular meals.

He has promised to send the US$4,500 needed to pay a smuggler to get her and her daughter north, and she is eagerly counting her last days at a job she has held for 26 years.

Like many workers at the packing plant, she complains Chiquita's new, more efficient system means she has to work harder for the same amount of pay -- about US$8 a day.

"I'm tired," she says, mopping sweat from her face with a rag while concentrating on the unending river of bananas. "This is too much."

Life in the banana factories

Still, many count Brizucla among the lucky. She didn't lose her job after Mitch, although the company put her on unpaid leave for several months after the storm killed nearly 10,000 people and caused an estimated US$10 billion in damages.

She's still paying off the US$1,297 loan from Chiquita that helped her clean up and pay expenses while she was unemployed.

Esteban Lopez wasn't as lucky. Hurricane Mitch cost him his job, and he was forced to work cutting material at a glove factory, where he earns US$45 a week -- US$20 less than he was making at the banana plantation.

Standing outside the factory in front of several Chiquita trailers parked alongside the road, Lopez says he'd rather work at the banana plantations, where the bosses are "strict but comply with all the benefits" like housing, schools, health insurance and bonuses. The bosses at his factory often mistreat workers, screaming at them if they don't work fast enough, he says.

Still, banana companies are planting fewer of their own plantations and buying from independent contractors whose workers are harder for unions to organize.

"The unions are facing their demise," says Stephen Coats, executive director of US/Labor Education in the Americas Project, a nonprofit group that supports labor rights in Latin America.

For Rivaldo Oyuela Martinez, the industry's decline in Central America is the end of an era. The quality control engineer from Honduras raised two daughters in a comfortable white clapboard house provided by Chiquita in what was dubbed the American Zone.

Most of the houses have been sold to private owners, and the only Americans left are an occasional Peace Corps volunteer renting out a room.

Oyuela remembers the neighborhood parties and the Chiquita executives playing golf on the neighborhood course. Now, the course's biggest clients are maquila executives from Asia, Oyuela says, pointing out a group of Filipinos and Japanese gathered on a green.

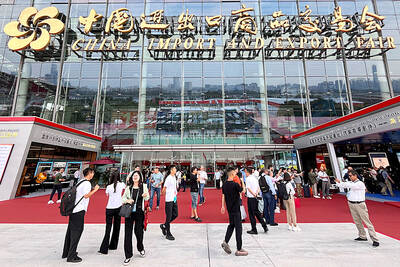

CARROT AND STICK: While unrelenting in its military threats, China attracted nearly 40,000 Taiwanese to over 400 business events last year Nearly 40,000 Taiwanese last year joined industry events in China, such as conferences and trade fairs, supported by the Chinese government, a study showed yesterday, as Beijing ramps up a charm offensive toward Taipei alongside military pressure. China has long taken a carrot-and-stick approach to Taiwan, threatening it with the prospect of military action while reaching out to those it believes are amenable to Beijing’s point of view. Taiwanese security officials are wary of what they see as Beijing’s influence campaigns to sway public opinion after Taipei and Beijing gradually resumed travel links halted by the COVID-19 pandemic, but the scale of

TRADE: A mandatory declaration of origin for manufactured goods bound for the US is to take effect on May 7 to block China from exploiting Taiwan’s trade channels All products manufactured in Taiwan and exported to the US must include a signed declaration of origin starting on May 7, the Bureau of Foreign Trade announced yesterday. US President Donald Trump on April 2 imposed a 32 percent tariff on imports from Taiwan, but one week later announced a 90-day pause on its implementation. However, a universal 10 percent tariff was immediately applied to most imports from around the world. On April 12, the Trump administration further exempted computers, smartphones and semiconductors from the new tariffs. In response, President William Lai’s (賴清德) administration has introduced a series of countermeasures to support affected

Pope Francis is be laid to rest on Saturday after lying in state for three days in St Peter’s Basilica, where the faithful are expected to flock to pay their respects to history’s first Latin American pontiff. The cardinals met yesterday in the Vatican’s synod hall to chart the next steps before a conclave begins to choose Francis’ successor, as condolences poured in from around the world. According to current norms, the conclave must begin between May 5 and 10. The cardinals set the funeral for Saturday at 10am in St Peter’s Square, to be celebrated by the dean of the College

CROSS-STRAIT: The vast majority of Taiwanese support maintaining the ‘status quo,’ while concern is rising about Beijing’s influence operations More than eight out of 10 Taiwanese reject Beijing’s “one country, two systems” framework for cross-strait relations, according to a survey released by the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) on Thursday. The MAC’s latest quarterly survey found that 84.4 percent of respondents opposed Beijing’s “one country, two systems” formula for handling cross-strait relations — a figure consistent with past polling. Over the past three years, opposition to the framework has remained high, ranging from a low of 83.6 percent in April 2023 to a peak of 89.6 percent in April last year. In the most recent poll, 82.5 percent also rejected China’s