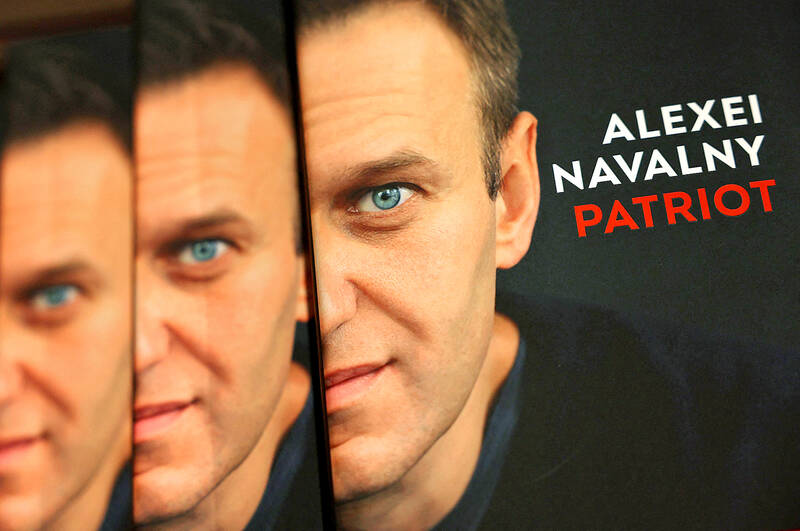

A much-awaited posthumous memoir by Russian dissident Alexei Navalny was published worldwide on Tuesday, containing sometimes humorous descriptions of his life including his time in prison and the now-famous prediction that he expected to die there.

Navalny, the top opponent of Russian President Vladimir Putin, began writing Patriot: A Memoir after his near-fatal poisoning in 2020.

The book recounts his youth, activism, personal life and his fight against Putin’s increasingly authoritarian hold on Russia.

Photo: AFP

Navalny worked on the manuscript and diaries that form the basis of the book until his death, aged 47, eight months ago.

US magazine the New Yorker and the Times of the UK published excerpts from the book earlier this month, including Navalny’s chilling expectation of his own death.

“I will spend the rest of my life in prison and die here,” he wrote on March 22, 2022.

“There will not be anybody to say goodbye to... All anniversaries will be celebrated without me. I’ll never see my grandchildren,” he wrote.

Navalny had been serving a 19-year prison sentence on “extremism” charges in an arctic penal colony.

His death on Feb. 16 at age 47 drew widespread condemnation, with many blaming Putin.

Navalny was arrested in January 2021 upon returning to Russia after suffering major health problems from being poisoned in 2020.

“The only thing we should fear is that we will surrender our homeland to be plundered by a gang of liars, thieves, and hypocrites,” he wrote on Jan. 17, 2022.

In a lucid, and sometimes lighthearted, tone Navalny also talks about matters far from politics or activism, such as his taste for cartoons and the love for his wife, Yulia Navalnaya.

He also describes the drudgery, and pointlessness of daily prison routines.

“At work, you sit for seven hours at the sewing machine on a stool below knee height,” he wrote. “After work, you continue to sit for a few hours on a wooden bench under a portrait of Putin. This is called ‘disciplinary activity.’”

Looking back at his childhood, Navalny remembered that the absence of chewing gum in the Soviet Union seemed to him to indicate his country’s inferiority on the world stage.

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, Navalny the student observed the corruption among university professors and the wealth grab by oligarchs in the new Russia.

Whatever hope he might have put in post-Soviet Russia’s political elite evaporated with former Russian presidents Boris Yeltsin, whom he calls a drunk surrounded by thugs, and Dmitry Medvedev, whom he calls both corrupt and stupid.

Navalny said he hated Putin, not only because he targeted him personally, but also because he thought the president had deprived Russia of two decades of development.

In an entry dated Jan. 17, Navalny responds to the question put to him by his fellow inmates and prison guards: Why did he come back to Russia?

“I don’t want to give up my country or betray it. If your convictions mean something, you must be prepared to stand up for them and make sacrifices if necessary,” he said.

In the arctic colony where he was sent in December last year, walks longer than half an hour were impossible because of the bitter cold, Navalny wrote.

On Feb. 16, he was declared dead, under unclear circumstances.

“Patriot reveals less about Navalny’s politics than it does about his fundamental decency, his wry sense of humor and his [mostly] cheery stoicism under conditions that would flatten a lesser person,” the New York Times said.

“It is important to publish these kinds of books,” said Caroline Babulle, at the book’s French publishers Robert Laffont, which has printed a first run of 60,000 copies.

Patriot, which had a worldwide run of several hundred thousand copies, topped Amazon.com’s list of bestselling books on Tuesday.

In the sweltering streets of Jakarta, buskers carry towering, hollow puppets and pass around a bucket for donations. Now, they fear becoming outlaws. City authorities said they would crack down on use of the sacred ondel-ondel puppets, which can stand as tall as a truck, and they are drafting legislation to remove what they view as a street nuisance. Performances featuring the puppets — originally used by Jakarta’s Betawi people to ward off evil spirits — would be allowed only at set events. The ban could leave many ondel-ondel buskers in Jakarta jobless. “I am confused and anxious. I fear getting raided or even

Eleven people, including a former minister, were arrested in Serbia on Friday over a train station disaster in which 16 people died. The concrete canopy of the newly renovated station in the northern city of Novi Sad collapsed on Nov. 1, 2024 in a disaster widely blamed on corruption and poor oversight. It sparked a wave of student-led protests and led to the resignation of then-Serbian prime minister Milos Vucevic and the fall of his government. The public prosecutor’s office in Novi Sad opened an investigation into the accident and deaths. In February, the public prosecutor’s office for organized crime opened another probe into

RISING RACISM: A Japanese group called on China to assure safety in the country, while the Chinese embassy in Tokyo urged action against a ‘surge in xenophobia’ A Japanese woman living in China was attacked and injured by a man in a subway station in Suzhou, China, Japanese media said, hours after two Chinese men were seriously injured in violence in Tokyo. The attacks on Thursday raised concern about xenophobic sentiment in China and Japan that have been blamed for assaults in both countries. It was the third attack involving Japanese living in China since last year. In the two previous cases in China, Chinese authorities have insisted they were isolated incidents. Japanese broadcaster NHK did not identify the woman injured in Suzhou by name, but, citing the Japanese

RESTRUCTURE: Myanmar’s military has ended emergency rule and announced plans for elections in December, but critics said the move aims to entrench junta control Myanmar’s military government announced on Thursday that it was ending the state of emergency declared after it seized power in 2021 and would restructure administrative bodies to prepare for the new election at the end of the year. However, the polls planned for an unspecified date in December face serious obstacles, including a civil war raging over most of the country and pledges by opponents of the military rule to derail the election because they believe it can be neither free nor fair. Under the restructuring, Myanmar’s junta chief Min Aung Hlaing is giving up two posts, but would stay at the