For Portland, social conflict and street clashes are nothing new. The Oregon city has a long history of pro-labor militancy coupled with an anti-fascist culture and defiance of authorities — but also, further back, a dark segregationist history.

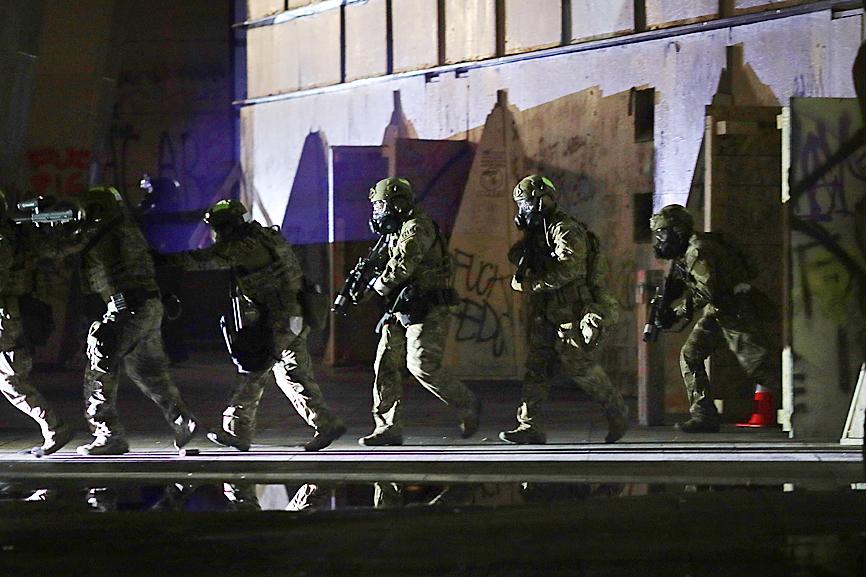

So Portland, despite its small black population, was not entirely a surprising venue for the weeks of anti-racism protests that have drawn national attention, prompting US President Donald Trump to send in federal agents in a highly controversial move.

Protesters have mobilized almost nightly since the death in Minneapolis, Minnesota, of George Floyd, a black man, under the knee of a white police officer in late May.

Photo: AFP

However, the city of 650,000 began forging its reputation for far-left militancy years ago, during the ferment and unrest of the 1960s, much like Seattle to the north and San Francisco farther to the south.

And since the 2016 presidential election, the city has come to symbolize virulent opposition to Trump and the Republican Party.

“Anti-authoritarian leftist politics ... have been present in Portland’s true protest culture for the last 30 years or so,” said Joe Lowndes, a political science professor at the University of Oregon.

Photo: EPA-EFE

The city earned the nickname of “Little Beirut,” a reference to the years-long war in Lebanon, after then-US president George H.W. Bush was met there with barricades, burning tires and hostile slogans.

“More recently, there’s been a lot of kind of anti-fascist work which has been done on the streets of Portland,” pushing back against far-right and white supremacist groups like the Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer, Lowndes said.

Protests and “violent attacks” on Portland residents by such far-right groups after Trump’s political emergence in 2016 spurred the development of “an active network of anti-fascist activists, who have grown over the last few years,” he added.

In November 2016, a demonstration against Trump’s election degenerated into three days of rioting and clashes with police.

The emergence early this year of the COVID-19 pandemic initially helped restore calm on the streets, but by then scenes of shaven-headed white supremacists and neo-Nazis clashing with hooded and black-garbed “antifa” anarchists had become commonplace.

“It is kind of a battleground for extremism,” Lowndes said.

“Because Portland has gained this reputation as kind of liberal, radical [and] progressive, that draws people in who share those views, and it becomes ... almost a feedback loop,” making the city ever more radical, said Steven Beda, a specialist in the region’s history at the university.

A mirror-image feedback loop in some rural parts of eastern Oregon attracted far-right militias and communities starting in the 1960s, Beda said.

Despite Portland’s current reputation as a leftist haven, the city and state were the product of fundamentally racist institutions, Beda said.

The Ku Klux Klan “had a huge presence in Oregon in the 1920s. It actually had the highest per capita membership numbers ... and there was a very, very close relationship throughout the 1920s between the political system and the Klan,” he said.

As recently as 1926, local laws forbade black people from entering the state under pain of whipping — a punishment to be repeated every six months if they remained.

So in Beda’s view, “any conversation about Portland’s radicalism, I think, has to exist alongside this other conversation about the history of exclusion and racism in Portland,” where only 6 percent of the population is black.

Further fueling the recent tension is the long-strained relationship between some residents and Portland law enforcement, which contributed to the locals’ strong pushback against the federal agents sent by Trump into the city in recent weeks, Lowndes said.

“The previous two or three years of protest policing in Portland have created a fracture with the community,” said Michael German, a former FBI agent now with the Brennan Center for Justice.

“The more aggression the police gave, the more aggression was returned,” he told the Washington Post.

LANDMARK CASE: ‘Every night we were dragged to US soldiers and sexually abused. Every week we were forced to undergo venereal disease tests,’ a victim said More than 100 South Korean women who were forced to work as prostitutes for US soldiers stationed in the country have filed a landmark lawsuit accusing Washington of abuse, their lawyers said yesterday. Historians and activists say tens of thousands of South Korean women worked for state-sanctioned brothels from the 1950s to 1980s, serving US troops stationed in country to protect the South from North Korea. In 2022, South Korea’s top court ruled that the government had illegally “established, managed and operated” such brothels for the US military, ordering it to pay about 120 plaintiffs compensation. Last week, 117 victims

China on Monday announced its first ever sanctions against an individual Japanese lawmaker, targeting China-born Hei Seki for “spreading fallacies” on issues such as Taiwan, Hong Kong and disputed islands, prompting a protest from Tokyo. Beijing has an ongoing spat with Tokyo over islands in the East China Sea claimed by both countries, and considers foreign criticism on sensitive political topics to be acts of interference. Seki, a naturalised Japanese citizen, “spread false information, colluded with Japanese anti-China forces, and wantonly attacked and smeared China”, foreign ministry spokesman Lin Jian told reporters on Monday. “For his own selfish interests, (Seki)

Argentine President Javier Milei on Sunday vowed to “accelerate” his libertarian reforms after a crushing defeat in Buenos Aires provincial elections. The 54-year-old economist has slashed public spending, dismissed tens of thousands of public employees and led a major deregulation drive since taking office in December 2023. He acknowledged his party’s “clear defeat” by the center-left Peronist movement in the elections to the legislature of Buenos Aires province, the country’s economic powerhouse. A deflated-sounding Milei admitted to unspecified “mistakes” which he vowed to “correct,” but said he would not be swayed “one millimeter” from his reform agenda. “We will deepen and accelerate it,” he

Japan yesterday heralded the coming-of-age of Japanese Prince Hisahito with an elaborate ceremony at the Imperial Palace, where a succession crisis is brewing. The nephew of Japanese Emperor Naruhito, Hisahito received a black silk-and-lacquer crown at the ceremony, which marks the beginning of his royal adult life. “Thank you very much for bestowing the crown today at the coming-of-age ceremony,” Hisahito said. “I will fulfill my duties, being aware of my responsibilities as an adult member of the imperial family.” Although the emperor has a daughter — Princess Aiko — the 23-year-old has been sidelined by the royal family’s male-only