Sergei Murza runs his fingers over the pink satin of a pointe shoe he has just finished making. Then he gives it the final test: The ballet slipper balances perfectly on its tip.

Murza produces the shoes in the Moscow workshop of Grishko, a company born in the chaos of the collapse of the Soviet Union and now one of the world’s top makers of ballet pointe shoes.

In a country better known for exporting oil and arms, Grishko is a rare success story for Russian artisanship, its shoes sold around the globe and gracing the stages of the world’s top ballet venues.

Photo: AFP

It is hardly surprising, founder Nikolay Grishko says, given the aura that surrounds Russia’s storied ballet tradition.

“It is in Russia that classical ballet has reached its highest level,” said the 71-year-old, who founded the company more than 30 years ago and continues to run it.

Grishko has diversified into clothing and other types of dance shoes, but the ballet line is the company’s heart and soul.

Nearly 80 percent of its production is for export, with the US — where the shoes sell under the brand name Nikolay — and Japan the top buyers.

Inspired by the liberalization of the Soviet Union under then-Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev, Grishko set up the company in 1988.

A former diplomat posted in Laos and economics professor, he found inspiration close to home.

“My wife was a dancer... I already knew what pointes were,” he said in his office at the factory, looking dapper in a dark suit and black-rimmed glasses.

When he launched the business, Russia’s big theaters such as the Bolshoi had their own in-house workshops making pointes.

That tradition is now gone, but the expertise built up over centuries lives on in his company.

“I took the best of the tradition of Russian pointes, which have been made since the end of the 19th century. This tradition was passed on in the theater workshops, but practically disappeared after the fall of the Soviet Union” in 1991, Ukrainian-born Grishko said.

Today he employs more than 500 people at workshops in Moscow, the Czech Republic and Macedonia. In Russia, a pair of Grishko pointes sells for the equivalent of 30 euros (US$33), in western Europe about twice that.

The Moscow workshop is housed on the grounds of the historic Hammer & Sickle Factory, a Soviet-era institution that once housed a steel plant.

Grishko’s master shoemakers work in silence as they produce 32,000 to 37,000 pairs of pointes per month, using only natural materials.

Cats roam around the work tables as artisans cut cloth, make their own glue, assemble the shoes and dry them in ovens, before a meticulous check for quality.

Among them are about 70 people who are deaf or hard of hearing, said Irina Sobakina, the 53-year-old deputy head of production, praising “the higher sensitivity of their hands.”

In the sewing workshop, Olga Monakhova, who is 56 years old and has worked at the factory for 27 years, recalls orders from famous dancers such as the Bolshoi’s Anastasia Volochkova and Nikolay Tsiskaridze.

Across the capital in her studio, Moscow Ballet Company dancer Alexandra Kirshina completes a rehearsal on pointes made especially for her.

“We wear them constantly, so it’s important that they fit perfectly,” the 28-year-old soloist said. “I used to dance in plastic pointes and I had big problems with my feet.”

Star dancers can go through up to 30 pairs of pointes a month, but professionals account for only 10 percent of Grishko’s buyers. Most sales go to ballet schools.

Grishko said he is even seeing a new kind of client: women who, tired of “boring aerobic exercises” and treadmills, are taking up ballet to keep fit.

Indonesia yesterday began enforcing its newly ratified penal code, replacing a Dutch-era criminal law that had governed the country for more than 80 years and marking a major shift in its legal landscape. Since proclaiming independence in 1945, the Southeast Asian country had continued to operate under a colonial framework widely criticized as outdated and misaligned with Indonesia’s social values. Efforts to revise the code stalled for decades as lawmakers debated how to balance human rights, religious norms and local traditions in the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation. The 345-page Indonesian Penal Code, known as the KUHP, was passed in 2022. It

‘DISRESPECTFUL’: Katie Miller, the wife of Trump’s most influential adviser, drew ire by posting an image of Greenland in the colors of the US flag, captioning it ‘SOON’ US President Donald Trump on Sunday doubled down on his claim that Greenland should become part of the US, despite calls by the Danish prime minister to stop “threatening” the territory. Washington’s military intervention in Venezuela has reignited fears for Greenland, which Trump has repeatedly said he wants to annex, given its strategic location in the arctic. While aboard Air Force One en route to Washington, Trump reiterated the goal. “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security, and Denmark is not going to be able to do it,” he said in response to a reporter’s question. “We’ll worry about Greenland in

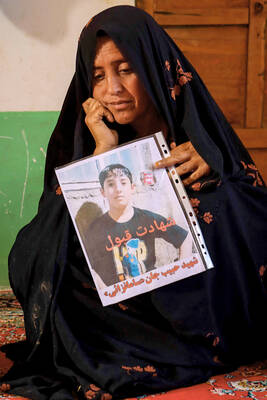

PERILOUS JOURNEY: Over just a matter of days last month, about 1,600 Afghans who were at risk of perishing due to the cold weather were rescued in the mountains Habibullah set off from his home in western Afghanistan determined to find work in Iran, only for the 15-year-old to freeze to death while walking across the mountainous frontier. “He was forced to go, to bring food for the family,” his mother, Mah Jan, said at her mud home in Ghunjan village. “We have no food to eat, we have no clothes to wear. The house in which I live has no electricity, no water. I have no proper window, nothing to burn for heating,” she added, clutching a photograph of her son. Habibullah was one of at least 18 migrants who died

Russia early yesterday bombarded Ukraine, killing two people in the Kyiv region, authorities said on the eve of a diplomatic summit in France. A nationwide siren was issued just after midnight, while Ukraine’s military said air defenses were operating in several places. In the capital, a private medical facility caught fire as a result of the Russian strikes, killing one person and wounding three others, the State Emergency Service of Kyiv said. It released images of rescuers removing people on stretchers from a gutted building. Another pre-dawn attack on the neighboring city of Fastiv killed one man in his 70s, Kyiv Governor Mykola