Historians are rethinking the way the Holocaust is being presented in museums as the world marks the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the last Nazi concentration camps this month.

Shocking images of the mass killings of Jews were “used massively at the end of World War II to show the violence of the Nazis,” historian Tal Bruttmann, a specialist on the Holocaust, told AFP.

But in doing so “we kind of lost sight of the fact that is not normal to show” such graphic scenes of mass murder, of people being humiliated and dehumanized, he said.

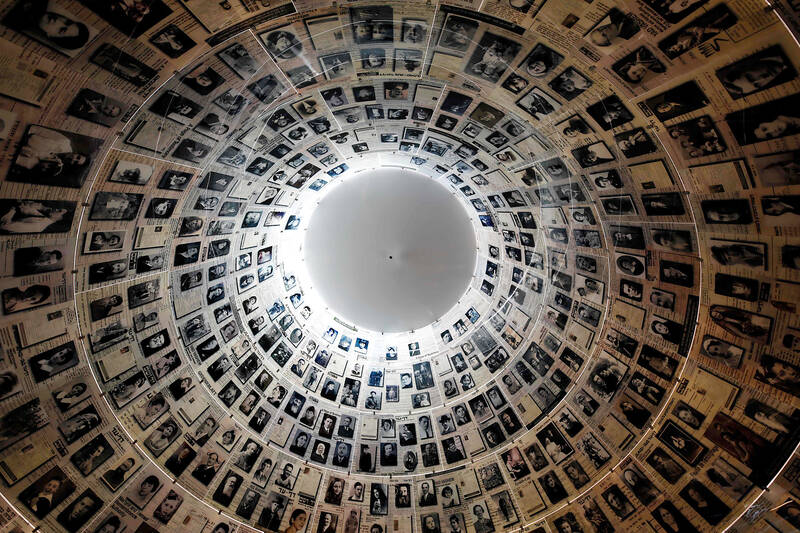

Photo: AFP 照片:法新社

Up to this year, visitors to the Memorial de Caen war museum in northern France were plunged into darkened rooms with life-sized photographs showing the horror of what happened in the camps and the mass executions earlier in the war.

“The previous generation of Holocaust museums used these images because it reinforces the horror,” said James Bulgin, who is in charge of the Holocaust galleries at London’s Imperial War Museum.

The difficulty with that is that it “denies the people within the images any capacity for agency or respect or identity,” he added.

Photo: AFP 照片:法新社

“The other problem with Holocaust narratives is that they tend to relate the history of what the Nazis and their collaborators did, not what Jewish people experienced,” argued the British historian.

Some six million were murdered in the Nazi’s attempt to wipe out European Jews.

“NO PHOTOS OF KILLINGS”

Photo: AFP 照片:法新社

Which is why “there are no photographs of killings” in the new, “almost clinically white” galleries dedicated to the Shoah at the Memorial de Caen, said Bruttmann, the scientific adviser on the project which opened this month.

“To show this absolute negation of human beings, there is no obligation to show images of such unprecedented violence,” said the memorial’s director Kleber Arhoul.

Historians at the Imperial War Museum had the same debate, but drew different conclusions.

They decided to still use graphic imagery. “The images exist as part of the historical record, we can’t suppress their existence,” said Bulgin. “But what we can do is meaningfully integrate them into the historical narrative.”

He said they did consider not using them but felt it could lead to misinformation. “All of that stuff exists on YouTube and Vimeo... but without us mediating it, shaping it, informing it, giving it context,” he added.

The curator said they “spoke to an enormous range” of Jewish groups and the “almost overwhelming consensus was that we should use the footage.”

However, graphic images of the genocide are shown in smaller formats, often on panels that carry a warning and that you have to turn over to see. Distinctions are also made between photos taken by Jews themselves and those taken by the Nazis in the Warsaw ghetto.

Israeli historian Robert Rozett argued that “we need these memorials to be aware of what human beings are capable of, and where open hatred can lead.”

At the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem, “there are pictures that show mass executions. They are not gigantic but they are there,” he said.

“The hardest pictures are not highlighted in any way,” he said. For example, those showing the massacre of Babi Yar, near Kyiv, in 1941 do not show the moment of the killings but the aftermath. And those of the mass graves do not show the bodies but the clothes of the victims strewn on the ground.

“YOU WANT THEM TO IDENTIFY”

Museums have also tended to concentrate on representing the ruthless, systematic efficiency of the Nazi death machine, experts say.

The first Holocaust memorials were “dark, oppressive spaces with a highly industrialized architecture that very much centers on Auschwitz,” Bulgin said. That was “enormously problematic and potentially slightly dangerous, because it has none of the human character that actually allowed it to happen.”

Which is why the London museum has tried to concentrate on this being a genocide “done by people, to people,” he said.

The new galleries in the Memorial de Caen have two distinct rooms. One on death camps like Auschwitz, the mass executions of the “Holocaust by bullets” and the mobile gas vans. The other deals with the concentration and work camps where prisoners were enslaved, brutalized and worked to death or died from hunger or disease.

But museums also have a duty to evoke the Jewish communities that were wiped out, Rozett insisted. “If you’re teaching the Holocaust, you have to talk about what happened before, about what was destroyed,” he said.

The first Holocaust room at the Imperial War Museum addresses this by showing a film called “The Presence of Absence.” At Yad Vashem, the visit begins with a sound and light show to draw people deep into those lost worlds.

“When you’re teaching, you want somebody’s mind and their heart,” it says. “You want them to identify. It’s not enough just intellectual engagement. There has to be something emotional, but not overriding emotional.”

(AFP)

本月是納粹集中營解放80週年紀念,歷史學家正重新思考博物館對大屠殺的展示方式。

研究大屠殺的歷史學家塔爾.布魯特曼對法新社表示,「二戰結束時,為了展示納粹的暴行,駭人的猶太人大屠殺影像被大量使用」。

但這麼做「我們似乎就忽略了一件事,就是展示如此血腥的大屠殺場景、人被羞辱和被非人道對待的場景並非常態」,他說。

到今年之前,參觀法國北部卡昂戰爭紀念館的遊客是被安排在黑暗的房間裡觀看真人大小的照片,了解集中營裡的恐怖情況,以及戰爭初期的大規模處決。

倫敦帝國戰爭博物館大屠殺展廳負責人詹姆斯‧布爾金表示:「上一代大屠殺博物館使用這些影像是因為它能強化恐怖」。

他補充道,這樣做的爭議在於「它剝奪了影像中人物所有的自主權、自尊或身份認同」。

這位英國歷史學家認為:「大屠殺敘事的另一個問題是,它傾向於講述納粹及其同路人的所作所為,而不是猶太人所經歷的事」。

納粹企圖消滅歐洲猶太人,約六百萬人被殺害。

「不展示殺戮的照片」

這就是為什麼卡昂紀念館新建的、「幾乎是純白的」猶太人大屠殺展廳裡「沒有殺戮的照片」,本月開幕的該展廳科學顧問布魯特曼說道。

卡昂紀念館館長克雷伯·阿胡爾表示:「大屠殺是對人類的全然否定,我們沒有義務展示這種前所未見的暴力影像」。

帝國戰爭博物館的歷史學家也做了同樣的辯論,但得出了不同的結論。

他們決定繼續使用血腥的影像。布爾金說:「這些影像是歷史記錄的一部分,我們無法隱藏它們的存在」。「但我們能做的是將它有意義地融入歷史敘事中」。

他說他們的確考慮過不展示這些影像,但覺得這可能會造成錯誤訊息。「所有這些內容都存在於YouTube和Vimeo上......但我們沒有對其進行介導、整理、報告及提供背景」,他補充道。

策展人表示,他們「與大量猶太族群談過」,並且「幾乎壓倒性的共識是我們應該使用這些影像」。

然而,種族滅絕的血腥影像以較小的畫幅顯示,通常是在印有警語的板子上,必須翻過來才能看到。也區分了猶太人自己拍攝的照片和納粹在華沙猶太區拍攝的照片。

以色列歷史學家羅伯·羅澤特認為,「我們需要這些紀念物來讓我們知道人類可以做出什麼樣的事,以及公開的仇恨會導致什麼後果」。

在耶路撒冷的以色列猶太大屠殺紀念館(Yad Vashem),「有一些大規模處決的照片。雖然不是很大尺寸的照片,但的確是有」,他說。

他說:「最令人難以卒睹的照片不會以任何方式突出顯示」。例如,1941年基輔近郊娘子谷大屠殺的照片並未呈現屠殺的當下,而是屠殺後的景況。萬人塚的照片並未有屍體入鏡,有的只是散落在地上的受害者的衣服。

「要讓觀眾感同身受」

專家表示,博物館的展示也傾向聚焦於納粹死亡機器的冷酷無情,及其系統性的效率。

布爾金說,第一批大屠殺紀念館是「黑暗、壓抑的空間,建築高度工業化,主要以奧斯維辛為中心」。這「有極大的問題,而且可能有點危險,因為它並未顯示人的元素,表示大屠殺是人為的」。

這就是為什麼倫敦的帝國戰爭博物館要強調這是一場「人對人實施的」種族滅絕,他表示。

卡昂紀念館的新展廳有兩個不同的展間。一個是展示奧斯威辛集中營之屬的死亡集中營、「子彈大屠殺」和流動毒氣車的大規模處決。另一個則是聚焦集中營及勞改營,猶太人那裡被奴役、虐待、操勞致死、餓死或病死。

但羅澤特堅信,博物館也有責任喚起人們對被消滅的猶太族群的關注。「若你要講授大屠殺,你必須講述大屠殺發生之前的情況,講述被摧毀的是什麼東西」,他說。

帝國戰爭博物館的第一個大屠殺展間放映一部名為「缺席的存在」的影片,來探討這個問題。以色列猶太大屠殺紀念館則是以一場聲光表演揭開序幕,帶領參觀民眾深入那些消失的地方。

它說道:「你教學的時候,是要訴諸人的思想和心靈」。「你希望他們感同身受。只有智識的投入是不夠的。必須有一些情感上的投入,但不能是壓倒一切的情緒」。

(台北時報林俐凱編譯)

An automated human washing machine was one of the highlights at the Osaka Kansai Expo, giving visitors a glimpse into the future of personal hygiene technology. As part of the event, 1,000 randomly selected visitors were given the chance to try out this cleansing system. The machine operates as a capsule-like chamber where warm water filled with microscopic bubbles gently washes away dirt. The 15-minute process also includes a drying phase, removing the need for users to dry themselves manually. Equipped with advanced sensors, the device monitors the user’s biological data, such as their pulse, to adjust water temperature and other settings

Britain’s National Gallery announced on Sept. 9 that it will use a whopping £375m (US$510m) in donations to open a new wing that, for the first time, will include modern art. Founded in 1824, the gallery has amassed a centuries-spanning collection of Western paintings by artists from Leonardo da Vinci to J.M.W Turner and Vincent van Gogh — but almost nothing created after the year 1900. The modern era has been left to other galleries, including London’s Tate Modern. That will change when the gallery opens a new wing to be constructed on land beside its Trafalgar Square site that is currently

Firefighters might face an increased risk of developing “glioma,” a type of brain cancer, due to certain chemicals encountered on the job. A recent study analyzed glioma cases and found clear connections between the genetic patterns of affected firefighters and their exposure to these harmful substances. The study found that firefighters exhibited significantly higher levels of specific mutational signatures in their glioma cells compared to individuals in other occupations. These signatures — unique patterns of genetic changes in DNA — help scientists trace the source of mutations. Earlier research has associated these mutations with certain chemicals found in fire

It is a universally acknowledged truth that Jane Austen, born in 1775, is one of the most beloved English novelists, and that her works still inspire readers today. She is renowned for her novels Pride and Prejudice, Emma, and Sense and Sensibility. Her stories often explore themes of love, marriage, and social status in late 18th-century British society and are written with wit and insight. To honor her legacy, the Jane Austen Festival is held every September in Bath, England. She lived there for several years, and the city is depicted in two of her novels. The festival began in 2001