When the world’s top gas traders met late last month at a canal-side hotel on the outskirts of Amsterdam, the atmosphere was business-as-usual: coffee, croissants and wrangling over deals for the upcoming winter. Then came news of a leak at Europe’s biggest liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant, located above the Arctic Circle in Norway.

The problem — discovered during a planned test of the facility’s safety systems — was quickly repaired, but not before it caused a momentary spike in the price of natural gas. Back in the Netherlands, it served as an uncomfortable reminder of the power of a single company, Equinor.

In the more than two years since Russia invaded Ukraine, sending energy prices soaring, the Norwegian oil and gas giant has quietly picked up the crown that once belonged to Russia’s Gazprom. Norway now supplies 30 percent of the bloc’s gas. Gazprom provided about 35 percent of all Europe’s gas before the war. Of the more than 109 billion cubic meters of natural gas Norway exported to Europe last year — enough to power Germany until 2026 — about two-thirds was marketed and sold by Equinor.

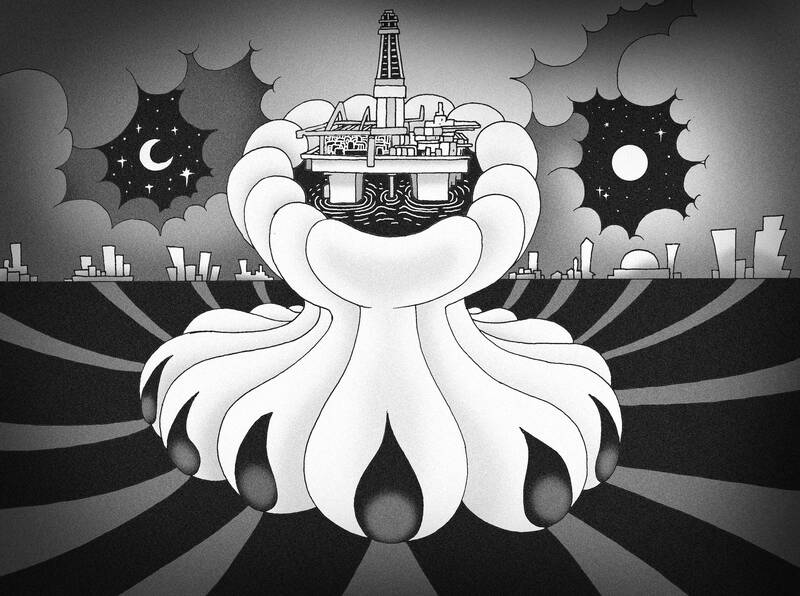

Illustration: Mountain People

So long as the bloc continues to depend heavily on fossil fuels, Norwegian hydrocarbons would be essential to keeping the lights on in Europe.

Equinor’s visibility “dramatically changed with reduced flows from Russia,” Equinor executive vice president of marketing, midstream and processing Irene Rummelhoff said. “There was a point in time where [Europe] almost took us for granted. That is no longer the case.”

The company’s new prominence has also raised questions about whether European leaders are, once again, putting their countries at risk by relying too heavily on a single supplier. Although Norway is perceived as a steady trading partner with a long and consistent history of delivering energy to Europe, extended outages and its handling of maintenance challenges, both of which affect energy prices, have had ripple effects across the continent.

Part of the company’s good fortune has to do with a broader shift in Europe’s relationship to fossil fuels, Nordea Bank chief analyst for sustainable finance Thina Margrethe Saltvedt said in an interview.

Five years ago, “there was a lot of talk about the green transition and how we were starting to see the oil and gas industry sunset,” she said. “Then COVID happened, then the war in Ukraine and now you simply don’t see it anymore. The focus has turned to energy security.”

The notion that gas would not disappear any time soon, a view strongly endorsed by the gas industry, has thrust Norway to the center of the conversation around securing Europe’s energy resources.

German Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Action Robert Habeck — who is also in charge of climate policy in the region’s biggest economy — made an official visit to Oslo in early January last year. Two months later, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen traveled to Norway’s Troll natural gas field, which provides 10 percent of the continent’s supplies.

European Commissioner for Energy Kadri Simson has also visited Norway twice in the past two years. Speaking at an event in the Norwegian capital in March, Simson told a hall filled with the country’s oil and gas elite that “the EU continues to count on Norway as a partner for conventional sources,” and offered her appreciation for its help during the energy crisis.

Because Norway’s gas prices are higher than Russia’s, there was some fuming after Russian exports shrank about Norway benefiting at Europe’s expense.

However, criticism abated as governments and traders accepted the new market conditions. The non-EU member has never been shy about the importance it places on gas — Norway has long advocated that gas should place a central role in the bloc’s green transition — and it is finding more willing counterparts.

Late last month, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz thanked Norway for enabling his country to become independent of Russian gas “within just a few months,” and praised it as “the perfect partner” for securing Germany and Europe’s supply.

Norway’s new role as gas purveyor to Europe has been profitable — gas exports hit a record high of 1.4 trillion kroner (US$130 billion) in 2022 — but it has also cast a question mark over Norway’s green future. While the country has become a leader in initiatives such as the transition to electric vehicles, the recent surge in demand for gas has had the effect of redirecting financial resources and talent back into the oil and gas sector.

Organizations such as Greenpeace have expressed concern that Europe’s embrace of Norwegian gas could come at the expense of the broader green transition.

For traders, going all in on Equinor brings a different set of problems.

Equinor’s growing relevance in Europe came into sharp focus last year, when the company announced that maintenance at some of its biggest gas facilities was being extended. Within minutes, gas prices rose almost 20 percent.

The response was especially intense as traders had mostly been betting that prices would slump. Sluggish demand and that the region’s gas inventories would be full by the end of the summer had led them to think that Europe had finally gotten over the worst of the energy crisis. Unusually hot weather on the continent, which normally increases energy use, amplified concern.

The unplanned outages severely reduced Norway’s exports for a few weeks and prompted trading desks across the continent to weigh the “Equinor maintenance effect” more heavily in their models. As the price of gas became even more exposed to the company’s status, traders started to pay closer attention to the daily messages sent out by another Norwegian company, Gassco, about changes to maintenance schedules across the country.

Within Equinor, there are “information barriers and procedures to ensure compliance with regulations so that all market participants can access market sensitive information at the same time,” a company spokesman said, adding that Gassco acts as a “neutral and independent system operator.”

Traders were already on alert for surprise outages. Until the end of 2021, Gazprom had mostly been a reliable supplier — a big reason why gas prices stayed stable over the past decade. When interruptions suddenly started to happen more frequently, prices spiked, triggering the energy crisis.

What nobody knew back then is that reducing gas flows was part of the run-up to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Around November, traders started to account for the loss of Russian supply in their pricing models.

Europe is on a far better footing than it was a year ago, but circumstances remain volatile. Any threat to fuel supply can roil markets, and that, in turn, can have downstream effects: Persistent price swings in the natural gas market can encourage industrial companies to limit their fuel usage and push household bills higher.

“Norway is expected to meet more of Europe’s gas needs this summer as its facilities bounce back from the extensive maintenance seen last year,” BloombergNEF’s Nnenna Amobi wrote in a note on May 1.

“But, unplanned outages could yet curtail flows and send prices upward,” she added.

At the same time, natural gas supplies from Norway might reach a new record this year. Equinor has been working to increase its capacity, and to reduce bottlenecks by streamlining maintenance work. The mantra within the country’s government — often repeated by Norwegian Minister of Energy Terje Aasland — is that Norway will be a “stable and long-term supplier of energy” for decades to come.

It remains to be seen whether that will pan out. With a new wave of LNG from the US and Qatar coming online in the next few years, “the importance of Equinor and Norway’s gas to Europe is going to eventually decline,” Bank of America European energy research head Christopher Kuplent said, adding that Norway would “find it hard to organically grow its gas production and therefore export substantially more.”

The new projects would “make it, at least on paper, a little more comfortable for the European gas consumer to negotiate prices down,” he said.

Moreover, Rummelhoff said that a jump in the volumes of LNG being imported to Europe recently has already helped “normalize the market.”

For now, focus within Equinor is on keeping things running as smoothly as possible.

“Do we feel under pressure? We’ve always felt that,” Equinor executive vice president of exploration and production in Norway Kjetil Hove said.

A: Apart from the musical Sunset Boulevard, Japanese pop diva Ayumi Hamasaki is also touring Taiwan after a 17-year wait. She’s holding two concerts starting tonight. B: Ayu has the most No. 1 hits of any Japanese solo artist, with 33 total. A: “Time” magazine even crowned her as “The Empress of Pop.” B: She staged shows in Taipei back in 2007 and 2008, causing an “Ayu fever” across Taiwan. A: Unfortunately, the singer has been deaf in her left ear since 2008, and is gradually losing hearing in her right ear. I’m so excited to see her singing in Taipei again. A: 除了音樂劇《日落大道》,日本歌后濱崎步睽違17年,今晚起在台北熱唱兩場。

Thailand and Cambodia are engaged in their worst fighting in over a decade, exchanging heavy artillery fire across their disputed border, with at least 30 people killed and tens of thousands displaced. Tensions began rising between the Southeast Asian neighbors in May, following the killing of a Cambodian soldier during a brief exchange of gunfire, and have steadily escalated since, triggering diplomatic spats and now, armed clashes. WHERE DOES THE DISPUTE ORIGINATE? Thailand and Cambodia have for more than a century contested sovereignty at various undemarcated points along their 817km land border, which was first mapped by France in 1907 when Cambodia was

Alan Turing, celebrated as the “father of computer science,” was a brilliant mathematician and scientist. Born in London in 1912, Turing showed exceptional talent in mathematics and science from a young age. At 16, he understood Albert Einstein’s work without difficulty. This intelligence carried him through studies at Cambridge University and later at Princeton University in the US, where he further explored complex mathematical theories. In 1936, Turing introduced the concept of the Turing machine, a theoretical device for solving mathematical problems. He described it as having an infinite tape on which symbols could be read, interpreted, and modified. With simple

A: After touring Taipei, the play Life of Pi is now heading to Taichung. You wanna go? B: Did you forget? We’re going to Taipei this weekend to see the musical Sunset Boulevard and go to Japanese pop diva Ayumi Hamasaki’s concert. A: Oh yeah, that’s right. The classic composed by Andrew Lloyd Webber is touring Taiwan for the first time. B: I heard that it’s adapted from a 1950 film with the same title. A: And the show will feature legendary soprano Sarah Brightman, who is finally returning to the musical stage after 30 years. We can’t miss it. A: 在台北巡演後,戲劇《少年Pi的奇幻漂流》本週起將移師台中。要去嗎?