Chinese Practice

作繭自縛

(zuo4 jian3 zi4 fu2)

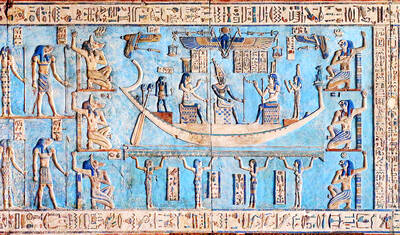

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

to spin a cocoon and entangle oneself

華特‧司各特爵士一八○八年的作品《Marmion: A Tale of Flodden Field》(瑪米恩:佛洛登戰役的故事)中,描述豐特萊的瑪米恩勳爵企圖陷害和謀殺情敵,後來一五一三年到了佛洛登的戰場上才發現,他的情敵不但還活著,而且還要找他報仇。瑪米恩發覺,自己所陷入的一連串困局,都是起因於他自己原先的詭計,於是他感嘆道:「Oh, what a tangled web we weave when first we practice to deceive!」(噢,我們起初為了欺騙所羅織的謊言之網,是多麼地糾結!)

這句話──無論是引用部份或整句──可用來指企圖藉謊言來獲得利益,以及必須羅織更多謊言,來為自己捏造的不實陳述自圓其說的愚蠢行為。

這個比喻顯然是在說蜘蛛網,蜘蛛網是錯綜複雜的網,其作用是誘捕獵物。「weave」(編織)這個動詞很有畫面,且在這個句子中押頭韻,但正確的寫法應為「to spin a web」。我們也可以說「spinning a web of lies」(羅織謊言之網)。中文有個類似成語──「作繭自縛」(吐絲作繭來纏住自己),但它所指的不是蜘蛛的網,而是蠶的繭。

在唐代,多產的詩人白居易(西元七七二~八四六年)寫了一首詩,題為《江州赴忠州至江陵已來舟中示舍弟五十韻》,其中有一句「燭蛾誰救護,蠶繭自纏縈」(蠟燭讓蛾身陷險境,蠶被自己織的繭纏住),暗示蛾被火焰吸引、蠶「自我圈閉」的傾向,不可避免地會使其陷入不利情況。

北宋僧人釋道原西元一○○四年作《景德傳燈錄》,記述禪宗大師及其他著名佛教僧侶的行誼,在〈卷二九.十四科頌.善惡不二〉中,收錄了南朝梁的誌公和尚(西元四一八~五一四年)語錄,其中有一句:「聲聞執法坐禪,如蠶吐絲自縛。法性本來圓明,病癒何須執藥」(信徒坐禪修習佛法,就像是蠶吐絲把自己綑綁起來。我們本來就有佛性,不必靠外在修練,就像沒生病的人何必吃藥呢?)誌公和尚的意思是說,佛法存在於一切事物中,可以自由地學習,但若把理解佛法的方式只限定在坐禪冥想,那就是自我設限了。

後來,宋代詩人陸游(西元一一二五~一二○九年)在《劍南詩稿‧書嘆》中寫道:

「人生如春蠶,作繭自纏裹」(人生就像春天的蠶,作繭把自己纏裹起來),但此處他比較是在說生命的不同階段,而不是自我設限的危險。儘管如此,我們可以在「蠶繭自纏縈」、「蠶吐絲自縛」和「作繭自纏裹」這三句之中,看到成語「作繭自縛」的元素。

「作繭自縛」現今的意義是指做了某事,結果反而使自己陷入困境。

(台北時報林俐凱譯)

他這個計謀其實是作繭自縛──想整對手,結果反而害到自己。

(His plan backfired: he wanted to mess with his opponent, but ended up harming himself.)

貪婪的人執著於追求金錢、感情和權力,身陷其中無法解脫,這就是作繭自縛。

(The greedy devote themselves to the pursuit of money, sex and power, and end up getting caught up in it, ensnared in a trap of their own making.)

英文練習

what a tangled web we weave

when first we practice to deceive

Sir Walter Scott’s 1808 work Marmion: A Tale of Flodden Field relates the story of how Lord Marmion of Fontenaye attempts to frame and murder a love rival, only to find later, on the battlefield of Flodden Field in 1513, that his rival was still alive and seeking vengeance. Realizing he had been entrapped by events initiated by his own attempts at deception, Marmion laments, “Oh, what a tangled web we weave when first we practice to deceive!”

That line can be quoted — either in part or in full — to express the folly of trying to profit by telling untruths, and having to create a web of lies to bolster a false narrative of one’s own invention.

The metaphor is presumably talking of the spider’s cobweb, an intricate network designed to entrap prey. The verb “weave” is evocative and alliterates, but the proper collocation is “to spin” a web. We can also talk of spinning a web of lies. A comparable Chinese idiom is 作繭自縛, “to spin a cocoon and entangle oneself,” referring not to the spider’s web but to the silkworm’s cocoon.

In the Tang Dynasty, the prolific poet Bai Juyi (772–846) wrote a poem entitled Going from Jiangzhou to Zhongzhou, I Arrived by Boat at Jianglu and Showed My Younger Brother These 50 Rhymes, which included the lines 燭蛾誰救護,蠶繭自纏縈 (the candle imperils the moth, the silkworm entangles itself in its spun cocoon), suggesting that the predispositions of the moth — attraction to the flame — and of the silkworm — its “self-entrapment” — unavoidably set them at a disadvantage.

In 1004, in the Northern Song Dynasty, the monk Shi Daoyuan completed the jingde chuandeng lu (Record of the Transmission of the Lamp), a record of Ch’an (Zen) masters and other prominent Buddhist monks. In Chapter 29 he references the monk Zhi Gong (418–514) of the Southern Liang Dynasty, whom he attributes as writing 聲聞執法坐禪,如蠶吐絲自縛。法性本來圓明,病愈何須執藥 (Disciples observing the dharma [Buddhist teachings] and sitting in meditation are akin to a silkworm spinning silk thread and binding itself; [in fact] the dharma-nature is clear for all to see: if you are recovering from a sickness, why take medicine?) Zhi Gong’s point was that to constrain yourself to meditation as a way to understand the dharma — which is present in all things and therefore freely available to study — you are limiting your ability to do so.

Later still, the Song Dynasty poet Lu You (1125–1209) would compile the jiannan shi gao (Collected Poems of Jiannan), which contained a poem including the line 人生如春蠶,作繭自纏裹 (Life is like a silkworm in spring, spinning a cocoon around itself...), although here he is talking more about the different stages of life, and not an inherent danger or self-enforced limitation. Still, between the three versions — 蠶繭自纏縈, 蠶吐絲自縛 and 作繭自纏裹 — we see all the elements of the idiom 作繭自縛.

It now means to entangle yourself in a situation due to your own actions.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

The politician’s lies are coming back to haunt him. Oh, what a tangled web we weave...

(這個政客的謊言現在正反過頭來讓他陷入困境,噢,他真是自作自受。)

I think you ought to come clean with him right now. You know what they say about tangled webs once you start trying to deceive people.

(我覺得你現在應該跟他說實話。一旦你開始騙人,你反而會作繭自縛。)

It graced statues, colored coffins, and decorated artifacts. It is Egyptian blue, the world’s oldest-known synthetic pigment born in ancient Egypt. Despite its name, it is not limited to a single hue. It ranges from deep blue to greenish tones, often glowing with an almost unearthly brilliance. __1__ In response, the ancient Egyptians developed a synthetic alternative. Not only was it visually striking, but it was also more affordable than imported indigo or natural lapis lazuli. Traces of the pigment have been discovered far beyond Egypt, from wall paintings in Pompeii to tiles in Mesopotamia. However, Egyptian blue began to fall

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Just yesterday, the boy had helped hang the lucky red couplets. Tonight, as firecrackers signaled the New Year, he lay in bed burning with a surging fever. The herbalist checked the boy’s pulse and went still. “The only cure is in the county town across the mountains,” he said. “But the snow is deep, and the shops are shuttered until the Fourth Day.” The boy’s father looked at the window. “I will go.” “The roads are impassable for a cart,” the herbalist warned. “And too far for a man on foot.” The concerned neighbor

Contrary to popular belief, glass bottles may pose a greater microplastic risk than plastic ones. A recent study found that beverages stored in glass bottles can contain up to 50 times more microplastic particles than those in plastic containers. Researchers traced most of the contamination to the paint on the outside of the metal caps. The particles found in the drinks matched the cap’s coating in both color and composition. Experts suggest the issue may result from microscopic scratches that form as caps rub against each other during transport or storage. Such scratches can damage the painted coating, leading

Many animals spend the winter in a deep, low-energy state known as “hibernation.” When food becomes scarce and cold conditions drain body heat, bats, hedgehogs, and some ground squirrels retreat to safe shelters. Their bodies slow down to save energy: heart rates drop, breathing becomes shallow, and body temperature falls. Plenty of preparation goes into hibernation. Shorter days and falling temperatures provoke these animals to eat more and store fat, which sustains the brain and other organs. Inside the body, hormones guide this seasonal change, triggering specific behavior and switching the system to energy-saving mode. Hibernation is not the only winter survival