Chinese practice

一知半解

having limited understanding of a matter

照片:維基共享資源

(yi1 zhi1 ban4 jie3)

英國科學家及哲學家弗朗西斯‧培根(西元一五六一~一六二六年),是提倡經驗主義作為獲得知識之方法的先鋒,他主張以嚴格的科學方法來質疑我們對世界的了解。

培根在他一六○一年的文章〈論無神論〉中寫道:「一點點的哲學,會讓人的思想傾向於無神論;但深入鑽研哲學,便會把人的心智帶向宗教。」

當然,培根寫作此文的時代背景,普遍仍是宗教掛帥的。

這句話的宗教內容是否為真,並非此處的焦點,對我們而言重要的是培根此言之含義──學習得不完整反而會造成誤導,讓人自以為知道的比實際所知還多,因此我們對事物必須先有全面的認識,才能夠對其作出適切的評論。

在一六九八年集結出版,名為《The Mystery of Phanaticism》(盲信之謎)的一批匿名信中提到了培根的概念,並闡述了這個想法:

「培根大人知道得很清楚,一點點的知識容易讓人自我膨脹、變得輕率,但更多的知識會將他們拉回正軌,並讓他們對自我有謙卑的認識。」

這也就是說,少量的知識會讓人對一己所學驕傲自滿,變得自我迷戀,除非他們後來有更全面的理解,否則他們不會對其所知所學做合理的評估。

十年之後,英國詩人亞歷山大‧波普(一六八八~一七四四年)在他一七○九年的作品〈論批評〉中,把這概念寫成了詩句:

膚淺之學乃危殆之事;

窮經深探,始能一嚐皮埃里亞百靈甘泉。

淺沾使人徒入迷津;

飽學深思終可戒懵增慧。

希臘神話中,有雙翅膀的飛馬珀伽索斯是海神波塞頓的孩子,馬蹄所踏之地,就會冒出泉水,稱作「皮埃里亞泉」,傳說飲此泉水的人,都會得到靈感與知識。

波普的詩句即為英文諺語「a little learning is a dangerous thing」(有一點點的知識是件危險的事)的出處。在一七七四年版的《Gentleman and Lady’s Complete Magazine》中,一篇文章引用這句話時出了錯,變成:「誠然,波普先生說,『A little knowledge is a dangerous thing』」。

波普的原句「a little learning」和錯引的「a little knowledge」這兩種版本今皆通行,用來指人有了一些知識就以為自己是專家,從而犯下錯誤。

「A little knowledge is a dangerous thing」若翻譯成中文,可譯為「一知半解是危險的」,或是「淺學誤人」。「一知半解」是個成語,其用法大約可歸成兩類,一為單純形容人對事物的了解有限、不夠深入;另一為推衍至語境中的隱含意,意指對事物只有皮毛的知識而妄加行動,可能造成禍害與危險。

成語「一知半解」,一般認為出自宋代著名理學家張栻(西元一一三三~一一八○年)的〈寄周子充尚書〉。這篇文章有一部分談到他即知即行、知行合一的理學觀,他說:

「蓋致知力行,此兩者工夫互相發也」(「致知」與「力行」兩者是相輔相成的),又說:「若學者以想象臆度,或一知半解為知道,而日知之則無不能行,是妄而已」(但若為學時未求真知,光憑主觀揣度,或不求甚解,又以其為所知並據之而行,那麼所得的一切將會是虛妄不實的)。

有趣的是,無論是「A little knowledge is a dangerous thing」或「一知半解」,經驗主義或格物致知(探求事物的道理,求得真理),雖然產生於東西方不同時空、有著不同名稱,但都是源於哲學上知識論的探索。

(台北時報林俐凱譯)

很多人在一知半解之下簽約,承受極大風險,事後常導致許多糾紛。

(Many people sign contracts without fully understanding the implications, and get themselves in a lot of trouble as a result. This often leads to all kinds of conflict.)

抱歉,我對這個議題一知半解,所以不方便多作評論。

(Sorry, I don’t really know too much about this issue, so I don’t feel comfortable discussing it.)

英文練習

a little knowledge is a dangerous thing

The English scientist Francis Bacon (1561 - 1626) was an early advocate of empiricism as an approach to knowledge, and of the adoption of a rigorous scientific method for questioning what we believe we know about the world.

In his 1601 essay Of Atheism, Bacon writes: “A little philosophy inclineth man’s mind to atheism; but depth in philosophy bringeth men’s minds about to religion.”

Bacon was writing, of course, at a time when the prevailing outlook was still strongly religious.

The veracity of the religious message is not the subject at hand, however: The important thing for us here is Bacon’s implication that incomplete learning can mislead one into thinking one knows more than one does, and that one must attain a comprehensive understanding of a subject before it is safe to comment on it.

This idea was elaborated in a set of anonymous letters published in 1698 under the name The Mystery of Phanaticism, in a reference to Bacon’s concept:

“Twas well observed by my Lord Bacon, that a little knowledge is apt to puff up, and make men giddy, but a greater share of it will set them right, and bring them to low and humble thoughts of themselves.”

That is, a little knowledge will make people proud of their learning, and they will become enamored of themselves, and will not return to a more reasonable assessment of their knowledge until they understand the subject more fully.

A decade later, in his 1709 work An Essay on Criticism, the English poet Alexander Pope (1688 - 1744) wrote:

A little learning is a dangerous thing;

drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

there shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

and drinking largely sobers us again.

According to Greek mythology, the winged horse Pegasus, child of the god Poseidon, would cause a spring to emerge wherever he struck the ground with his hoof. One such spring was the Pierian spring, thought to bring inspiration and knowledge to everyone who drank from it.

From Pope’s verse we get the English proverb “a little learning is a dangerous thing.” Pope would be misquoted in an article published in a 1774 edition of Gentleman and Lady’s Complete Magazine, in which the writer says, “Mr. Pope says, very truly, ‘A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.’” Both versions — Pope’s “a little learning” and the misquote “a little knowledge” — are both used today to mean that a bit of knowledge can make a person believe they are more expert than they actually are, and that this can lead to mistakes being made.

In Chinese, the proverb can be translated as either 一知半解是危險的 (incomplete understanding is dangerous) or 淺學誤人 (shallow knowledge misleads). The phrase 一知半解 is, in itself, a Chinese idiom that can be used in two different ways: The first is simply to describe someone whose knowledge is limited, and not deep enough; the second contains the implication that somebody with only superficial knowledge taking action can lead to disaster or danger.

The idiom 一知半解 is generally acknowledged as originating in a letter the Song Dynasty Neo-Confucian rationalist scholar Zhang Shi (1133 - 1180) sent to Zhou Zichong, a government minister. In this letter, Zhang talks of the rationalist concept of the dialectical relationship between knowledge and action. He wrote, 蓋致知力行,此兩者工夫互相發也 (knowledge and action are equally imperative: the one bolsters the other), and 若學者以想象臆度,或一知半解為知道,而日知之則無不能行,是妄而已 (if the scholar, in studying, neglects to strive for the truth, and only relies on subjective assumption, or does not try to fully understand, acting according to what he knows, then it will all be in vain.)

It is interesting to note that both phrases — “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing” and “一知半解,” derive from a similar epistemology, despite being called different names and emerging in different places and at different times: Empirical inquiry in the West, and the Neo-Confucian striving for the truth and reason in China.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

He thinks he knows everything, but he doesn’t. He will cause problems if he implements that policy. A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.

(他自以為無所不知,其實並非如此。如果他把這個政策付諸實行,問題會層出不窮。一知半解是很危險的。)

I’m not sure you understand the complexity of this situation. Be careful how you proceed: A little learning is a dangerous thing.

(不知道你了不了解這情況的複雜性。淺學誤人,你得要小心你的做法。)

In an effort to fight phone scams, British mobile phone company O2 has introduced Daisy, an AI designed to engage phone con artists in time-wasting conversations. Daisy is portrayed as a kindly British granny, exploiting scammers’ tendency to target the elderly. Her voice, based on a real grandmother’s for authenticity, adds to her credibility in the role. “O2” has distributed several dedicated phone numbers online to direct scammers to Daisy instead of actual customers. When Daisy receives a call, she translates the scammers’ spoken words into text and then responds to them accordingly through a text-to-speech system. Remarkably, Daisy

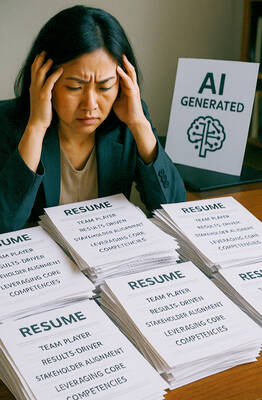

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Emma had reviewed 41 resumes that morning. While the ATS screened out 288 unqualified, she screened for AI slop. She could spot it a mile away. She muttered AI buzzwords like curses under her breath. “Team player.” “Results-driven.” “Stakeholder alignment.” “Leveraging core competencies.” Each resume reeked of AI modeling: a cemetery of cliches, tombstones of personality. AI wasn’t just changing hiring. It was draining the humanity from it. Then she found it: a plain PDF cover letter. No template. No design flourishes. The first line read: “I once tried to automate my

Every May 1, Hawaii comes alive with Lei Day, a festival celebrating the rich culture and spirit of the islands. Initiated in 1927 by the poet Don Blanding, Lei Day began as a tribute to the Hawaiian custom of making and wearing leis. The idea was quickly adopted and officially recognized as a holiday in 1929, and leis have since become a symbol of local pride and cultural preservation. In Hawaiian culture, leis are more than decorative garlands made from flowers, shells or feathers. For Hawaiians, giving a lei is as natural as saying “aloha.” It shows love and

1. 他走出門,左右看一下,就過了馬路。 ˇ He walked outside, looked left and right, and crossed the road. χ He walked outside and looked left and right, crossed the road. 註︰並列連接詞 and 在這句中連接三個述語。一般的結構是 x, y, and z。x and y and z 是加強語氣的結構,x and y, z 則不可以。 2. 他們知道自己的弱點以及如何趕上其他競爭者。 ˇ They saw where their weak points lay and how they could catch up with the other competitors. χ They saw where their weak points lay and how to catch up with the other competitors. 註:and 一般連接同等成分,結構相等的單詞、片語或子句。誤句中 and 的前面是子句,後面是不定詞片語,不能用 and 連接,必須把不定詞片語改為子句,and 前後的結構才相等。 3. 她坐上計程車,直接到機場。 ˇ She took a cab, which took her straight to the airport. ˇ She took a cab and it took her straight