Chinese practice

五十步笑百步

(wu3 shi2 bu4 xiao4 bai3 bu4)

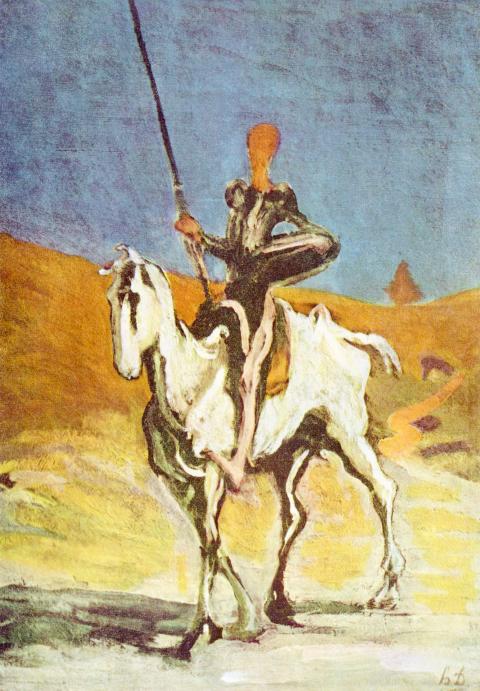

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

「The pot calling the kettle black」(鍋嫌水壺黑)這句話最早見於威廉‧佩恩的《孤獨的果實》(西元一六八二年出版),他在書中寫道:

「貪婪的人反對浪費、無神論者反對偶像崇拜、暴君反對叛亂,或騙子反對造假,還有酒鬼反對酗酒,就像是鍋子嫌水壺黑一樣。」

這句話是用來表示某人批評別人犯錯,但其實自己也犯了同樣的過錯。如果鍋子和水壺都被燻黑了,那麼鍋子怎能指責水壺也是黑的?

佩恩這句話的說法是比較有禮貌的版本。約翰‧克拉克一六三九年出版的諺語集中所收錄的另一版本是「the pot calls the pan burnt-arse」(水壺笑鍋子的屁股燒焦),指的是鍋子因放在煤炭上烤,底部被燻黑了,同樣的情況也發生於水壺。

然而這句話的英語原句似乎來自西班牙語,可追溯到塞萬提斯《唐吉訶德》的一六二○年英譯本,由托馬斯‧謝爾頓翻譯──其中有一句話「你就像俗話中煎鍋對水壺說的:『離開那裡吧,你這黑眼圈』。」

「The pot calling the kettle black」有另一種現代的解釋──這水壺是銅製的,且非常潔淨、光可鑑人,所以這鍋子看到的燒黑的形象其實是自己的鏡像。這種詮釋雖然讓這句話變成是一種心理投射,但仍與其現今用以形容偽善的原意相符。

由於這句話的出處跟種族問題並不相干,因此它應不致如人所疑慮的有種族主義色彩。

在台灣閩南語中,有這樣一句話:「龜笑鱉無尾,鱉笑龜粗皮」。

中文裡也有「五十步笑百步」的說法。

戰國時代哲學典籍《孟子》的〈梁惠王上〉寫道,梁惠王向孟子抱怨說,他是如何地絞盡腦汁、比鄰國國君花更多的心力處理國家事務,但「鄰國之民不加少,寡人之民不加多」(鄰國的人民沒有減少,我國的人民也沒增加)。

孟子認為問題不在這些狀況本身,而是在於梁惠王習於把矛頭指向外部因素而不反求諸己。孟子或許知道若直接點出梁惠王治國的失敗,會給自己招來禍害,因此改用軍事的隱喻來說明。他以 「王好戰,請以戰喻」(陛下喜歡戰爭,讓我用戰爭來做比喻)起頭。

然後孟子要梁惠王想像逃離戰場前線的士兵,問他怎麼看那些跑離五十步的人嘲笑跑離一百步的人膽小(「以五十步笑百步」)。梁惠王回答說:「不可,直不百步耳,是亦走也」(他們不該逃跑。雖然他們逃了不到一百步,但他們也都是逃了。)

然後孟子批評說,梁惠王把該國的饑荒完全歸咎於今年農作的歉收。孟子問道,這與刺殺了一個人然後說「非我也,兵也」(不是我殺的,是武器殺的)有什麼不同?孟子的意思當然是說,在怪別人之前,應該先省視自己。

(台北時報編譯林俐凱譯)

這兩國的國民素質都不好,但都五十步笑百步,只會互相看不起對方的行為。

(The people of both countries leave a lot to be desired, but they cannot see their own faults, they just look down on the other country.)

你遲到十分鐘,還有臉嘲笑遲到半小時的人,簡直是五十步笑百步!

(You turn up 10 minutes late and have the audacity to complain about people being 30 minutes late. Pot, meet kettle. Kettle, meet pot.)

英文練習

the pot calling the kettle black

The phrase “the pot calling the kettle black,” in that form, first appeared in print in Some Fruits of Solitude in Reflections and Maxims (1682) by William Penn, in which he wrote:

“For a Covetous Man to inveigh against Prodigality, an Atheist against Idolatry, a Tyrant against Rebellion, or a Lyer against Forgery, and a Drunkard against Intemperance, is for the Pot to call the Kettle black.”

The phrase has been taken to mean criticizing others for a fault that you also possess. If both pot and kettle are black, how can the former accuse the latter for having that same quality?

Penn’s version is put a little more politely than another that appeared in a 1639 collection of proverbs by John Clarke, which says “the pot calls the pan burnt-arse,” referring to the fact that the pan has a burnt bottom from being placed on hot coals, even though the same could be said for the pot itself.

The original form, in English, of the phrase appears to come from Spanish, however, and dates to a 1620 translation by Thomas Shelton of Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, which has the line “You are like what is said that the frying-pan said to the kettle, ‘Avant, black-browes’ [get out of there, black-eyes].”

Despite another modern interpretation of the phrase, which suggests that the kettle is, in fact, spotless copper in which the pot only sees its own reflection, therefore transforming the phrase into a case of psychological projection, the phrase is actually used in line with its original meaning of hypocrisy.

Due to its origins, the idiom is unlikely to contain any racial overtones, as some might fear.

In Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), there is the phrase, “the tortoise laughs at the soft-shelled turtle for lacking a tail; the turtle laughs at the tortoise for its thick skin.”

In Chinese, we have 五十步笑百步.

In the King Hui of Liang I chapter of the Warring States philosophical text the Mencius, the king complains to Mencius how he spends so much more time wracking his brains about affairs of state than the rulers of other states, and yet “the people of the neighboring kingdoms do not decrease, nor do my people increase.”

Mencius believes the problem lies not in the circumstances but in the king’s habit of blaming external factors. Probably aware of the trouble a blunt answer will put him in, Mencius leads in with a military metaphor. Tellingly, given the king’s apparent failings as a ruler, he starts with, “Your majesty is fond of war: Let me take an illustration from war.”

Mencius asks the king to imagine soldiers who flee from the front line of a battle, and asks him what he would think of those who ran 50 paces deriding those who had run 100: 以五十步笑百步. The king replies, “They should not do so. Though they did not run a hundred paces, they still ran away.”

Mencius then criticizes the king for blaming famine in the state entirely on the year’s harvest. He asks how this differs from stabbing a man and killing him, and then saying, “It was not I; it was the weapon.” His meaning, of course, was that one needs to take a close look in the mirror before attributing blame elsewhere.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

At the risk of being accused of the pot calling the kettle black, can I ask you not to be late tomorrow?

(雖然我這麼說可能是五十步笑百步,但我可以請你明天不要遲到嗎?)

Did he really accuse me of being rude? Talk about the pot calling the kettle black.

(他居然敢說我粗魯?真是五十步笑百步。)

Have you ever wondered why “Manila envelopes” carry that name? The answer lies in a plant native to the Philippines. Though a fruit-producing plant, abaca is most valued for its leaf stalks, which are __1__ to extract fibers known as “Manila hemp.” These fibers are known for their strength and resistance to saltwater. Because of its __2__ in sea environments, Manila hemp has long been used to make Manila rope, a staple in the sailing and maritime industries for centuries. It withstands harsh ocean conditions without its flexibility being __3__. Manila rope doesn’t break down easily when exposed to

China commemorated 80 years since the end of World War II last week with a massive military parade against a backdrop of a disputed history about who ultimately defeated Japan. The issues, including Japan’s reckoning with its wartime record in China, are bound to flare again in December, a flashpoint anniversary of the mass killing in Nanjing by invading Japanese troops. Below is an explainer about what the different — and disputed — points of view are. WHAT IS CHINA’S VIEW? For the Chinese government sitting in Beijing, this is a clear-cut issue: China sacrificed 35 million people in a heroic and brutal struggle

In a major step to combat carbon emissions, Norway’s pioneering “Northern Lights project” is set to expand its carbon capture and storage (CCS) capabilities. Backed by energy giants and the Norwegian government, this collaborative project is working to increase its annual carbon storage capacity from 1.5 million to over five million tons. Northern Lights focuses on capturing CO2 emissions from industrial sources across Europe and securely storing them underground. Captured CO2 will be liquefied and transported by ship to the storage facility located off the coast of Norway. It will be injected through pipes into geological formations about 2,600m below the

Rarely does Nature present such a striking contradiction as the one found in Lencois Maranhenses National Park. Located along Brazil’s northeastern coast, the park unveils breathtaking scenery, where rippling sands meet crystal-clear lagoons. Under the sun’s golden glow, the waters glitter in shades of turquoise and emerald. So surreal is this spectacle that visitors might wonder if they’re gazing at a digitally modified photo rather than a living landscape. Were it not for the unique geographical and climatic conditions, such a marvel would not exist. Unlike typical deserts, Lencois Maranhenses receives a substantial amount of rainfall, particularly during the rainy season