Chinese Practice

貪多嚼不爛

(tan1 duo1 jiao2 bu2 lan4)

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

bite off more than you can chew

《二刻拍案驚奇》是晚明凌濛初所編寫的通俗小說集,卷五的故事描述一群小偷趁元宵夜熱鬧人多好下手,便分頭行動。其中一個小偷尚未行竊,但看見一戶有錢人家的小孩打扮好出門,便跟蹤小孩到人多擁擠處趁亂把他擄走。但這小孩機靈,在被帶經過官轎旁便喊「有賊!」小偷便倉皇放下孩子逃走了。後來小偷與同夥會合,大家都有斬獲,只有這個小偷空手,他辯解說,他原先擄的那個小孩價值更高,他其實一點也不想放他走。眾賊聽了便說,你太過貪心,最後還不是空手而回?

文中實際用來形容小偷太過貪婪的句子即是「貪多嚼不爛」,字面上的意義是「嘴裡塞了太多食物,無法全部嚼碎」,延伸為貪婪之意,意思同英文的「biting off more than you can chew」。

如同中文的「貪多嚼不爛」,英文的「to bite off more than you can chew」很少用來指人一下子在嘴裡塞太多食物;這句話較常用作隱喻,表示人在念書或工作時一口氣處理超過自己能夠勝任的份量。

如同中文成語,此英文片語之起源並不在形容嚼食物。此片語一般認為是在一八七○年左右開始使用,當時菸草常用嚼的。當有人請嚼菸草,人們常會在菸草團上咬一大口,或許比他們能夠自如咀嚼的份量還多。因此,若某人咬下了超過他能咀嚼的份量,則表示了他眼前的任務艱鉅,也許是不可能達成的。

(台北時報編譯林俐凱譯)

你想一個晚上唸完全部課程,小心貪多嚼不爛,這樣不會有效果。

(I think studying the entire curriculum in one night is biting off more than you can possibly chew. It’s counterproductive.)

這個產品提案強調薄利多銷,又沒有足夠的出貨機制因應,恐怕是貪多嚼不爛了。

(This product proposal emphasizes small margins and rapid turnover, and there is no distribution system in place. It just seems overly ambitious.)

英文練習

bite off more than you can chew

The book Amazing Tales — Second Series is a collection of short stories written in the late Ming dynasty in vernacular Chinese by the author Ling Mengchu. The fifth chapter relates a story of how a group of thieves descends upon a crowd of revelers celebrating the Lantern Festival. The thieves split up and one, before he’s stolen anything, spots a child dressed in his finest clothes coming out of a wealthy family’s residence. The thief follows the boy and kidnaps him from under cover of a throng of people. Unfortunately for the thief, the child has his wits about him. As they are passing an official’s carriage, he shouts “Thief! Thief!” The man, panicking, runs off and rejoins his fellow thieves, the only one of them who returns empty-handed. He tries to explain himself, saying that the child would have been worth a fortune, and he really didn’t want to let him go. The other thieves look at him and say, “And where is the child now? You were greedy, and now you have nothing to show for yourself.” The actual phrase he used to mean being greedy was "貪多嚼不爛了", literally “eating so much that it’s difficult to chew” or, in plainer English, “biting off more than you can chew,” although here it is meant in a purely metaphorical sense.

Just like the Chinese idiom, the English metaphor “to bite off more than you can chew” is only rarely used as a reference to actually stuffing your face with food: it is more usually used in the sense of taking on more than you can reasonably manage, for example with study or work.

And just like the Chinese idiom, the origins of the English metaphor do not lie in chewing food. The phrase is thought to have originally come into usage around the year 1870, at a time when it was still common to chew tobacco. When offered a wad of chewing tobacco, people would take a big “bite” of the tobacco, much bigger than perhaps they were able to chew comfortably. That is, if a person has bitten off more than they can chew, the implication is that the task in front of them is daunting to say the least, and more than likely impossible.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

Don’t you think you’re biting off more than you can chew taking on the editor’s duties on top of your own work?

(你難道不覺得在你原本工作量之外再加上編輯的工作這樣負荷太多嗎?。)

A: I’m glad that the Grammys will honor the late pop diva Whitney Houston with a Lifetime Achievement Award. Who are this year’s leading nominees? B: Kendrick Lamar is leading the nominations with nine nods, followed by Lady Gaga with seven nods. Bad Bunny, Sabrina Carpenter and Leon Thomas each gained six nods. A: I heard that the song “Golden” from global animated blockbuster KPop Demon Hunters received three nominations, including Song of the Year. B: Blackpink’s Rose and Bruno Mars’ “APT.” also received major recognition with multiple nominations, including Record of the Year, setting a milestone for

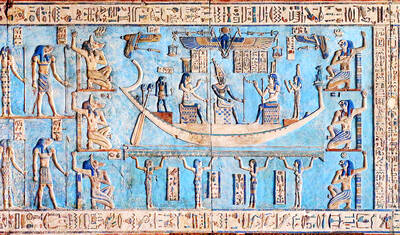

It graced statues, colored coffins, and decorated artifacts. It is Egyptian blue, the world’s oldest-known synthetic pigment born in ancient Egypt. Despite its name, it is not limited to a single hue. It ranges from deep blue to greenish tones, often glowing with an almost unearthly brilliance. __1__ In response, the ancient Egyptians developed a synthetic alternative. Not only was it visually striking, but it was also more affordable than imported indigo or natural lapis lazuli. Traces of the pigment have been discovered far beyond Egypt, from wall paintings in Pompeii to tiles in Mesopotamia. However, Egyptian blue began to fall

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Just yesterday, the boy had helped hang the lucky red couplets. Tonight, as firecrackers signaled the New Year, he lay in bed burning with a surging fever. The herbalist checked the boy’s pulse and went still. “The only cure is in the county town across the mountains,” he said. “But the snow is deep, and the shops are shuttered until the Fourth Day.” The boy’s father looked at the window. “I will go.” “The roads are impassable for a cart,” the herbalist warned. “And too far for a man on foot.” The concerned neighbor

Contrary to popular belief, glass bottles may pose a greater microplastic risk than plastic ones. A recent study found that beverages stored in glass bottles can contain up to 50 times more microplastic particles than those in plastic containers. Researchers traced most of the contamination to the paint on the outside of the metal caps. The particles found in the drinks matched the cap’s coating in both color and composition. Experts suggest the issue may result from microscopic scratches that form as caps rub against each other during transport or storage. Such scratches can damage the painted coating, leading