Until 1873, Japanese New Year, or shogatsu, followed the traditional lunar calendar. Since then, it starts on Jan. 1, in keeping with the Western Gregorian calendar, and lasts two weeks.

One important part is the thorough housecleaning, or oosoji, that must be done before New Year’s Day. The roots of this tradition are religious. According to Japan’s indigenous religion, Shinto, a god enters the house at New Year’s, and stays there for a few days.

Several days before the new year, the kadomatsu is displayed at the entrance of the house to greet the toshigami (New Year god). These are decorations that vary from region to region, and can include bamboo shoots, symbolizing prosperity; pine, representing longevity; and plum branches, for steadfastness.

Photo: AP

照片:美聯社

On New Year’s Eve, the Japanese eat a selection of dishes — osechi-ryori — many of which are sweet, sour, or dried, so they can be kept for a long time, as the tradition predates the arrival of the refrigerator. Traditionally, the women of the household prepared these dishes days before the New Year.

The traditional Japanese New Year’s Eve dish is toshi-koshi soba, a custom which started in the Edo period (1603–1868). Toshi-koshi means to cross from the old year to the new. Shrimp may also be eaten, as the shrimp’s curved back resembles that of an elderly person, and eating it is believed to promote long life.

A few minutes before midnight, some temples ring a large bell 108 times: in Buddhism, the number of earthly desires that cause humans suffering.

On New Year’s Day itself, people receive greeting cards called nengajo, and give children money in decorated envelopes, a tradition known as otoshidama. The amount depends on the child’s age. Families will then make their first visit to a shrine or temple, a custom called hatsumode, either on New Year’s Day itself or a few days after.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

在一八七三年以前,日本的新年,或者說shogatsu(日語:正月),是根據傳統的陰曆計算。一八七三年之後則是依照西洋的陽曆,從一月一日起開始新的一年。

準備過新年的重要工作叫做oosoji(日語:大掃除),是徹底打掃住家,而且必須在一月一日新年以前完成。這是源於宗教的傳統。日本傳統民族宗教神道教相信,神明會在新年進入家中,並住下幾天 。

新年的前幾天,人們會把一種叫做kadomatsu(日語:門松)的飾品裝在住家的入口處來歡迎toshigami(新年之神,日語:年神)。門松的做法依各地習慣而有所不同,可包括筍子、松樹枝和棗樹枝。筍子象徵繁榮昌盛,松樹象徵長壽,而棗樹枝則代表堅定不移。

在除夕夜,日本人會吃叫做osechi-ryori(日語:御節料理)的幾道菜,御節料理多為甜的、酸的、或是風乾的,以便保持得更久,這是尚未有冰箱的年代所留下的傳統。傳統上,家中的婦女在過年前便做好這些菜。

Toshi-koshi soba 是日本傳統的除夕夜菜餚,這是源自於江戶時代(一六○三年–一八六八年)的習俗。Toshi-koshi意指由舊年邁入新年。人們也可吃蝦,因為蝦彎曲的背很像老人,因此吃蝦也代表著有益於長壽。

在新年到來前幾分鐘,有些寺廟會鳴除夜鐘一百零八下:這在佛教中代表造成苦難的一百零八種俗世欲望。

在新年當天,人們收到叫做nengajo的賀卡,並給小孩用圖案信封裝著的壓歲錢,傳統上稱作otoshidama(日語:御年玉),其金額則是依據孩子的年紀而定。然後許多家庭也會在新年的第一天或之後的幾天到寺廟初詣,作開年首次參拜,此習俗稱作hatsumode(日語:初詣)。

(台北時報編譯林俐凱譯)

Denmark’s state-run postal service, PostNord, announced that it would cease letter deliveries at the end of 2025 due to the impact of digitalization. As 95% of its residents now use the Digital Post service, Denmark has seen a 90% decline in letter volumes since 2000, from 1.4 billion to 110 million last year. On top of that, the Postal Act of 2024 removes the government’s obligation to provide universal mail service and puts an end to postal exemptions from value-added tax, raising the cost of a single letter to 29 Danish krone (US$4.20). As a result, PostNord is switching

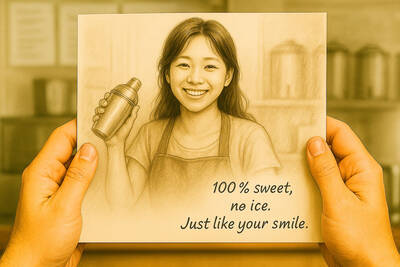

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 “One DA-BEI... WU LONG... NAI?” Yujing smiled as the foreigner struggled to order. He looked like an embarrassed puppy. She repeated the order in Chinese, then English: “Oolong milk tea, large size. Half sweet, no ice?” she said gently. He beamed — the kind of full-face, sunshine smile that Latinos are famous for. “Yes! That! You are... lo maximo… the best!” After he left, Lily nudged her. “Nice save. You’re getting the hang of it.” Yujing had taken this summer job at the bubble tea shop to build confidence and get work

When you think of the Netherlands, images of tulips, windmills, and iconic wooden shoes — known as “Dutch clogs” — may come to mind. These traditional shoes are rich in cultural significance. For centuries, Dutch clogs have been admired for their sturdy design and impressive craftsmanship, making them a fascinating symbol of Dutch heritage. Dutch clogs date back to the Middle Ages. During that time, farmers and laborers needed durable shoes to cope with the region’s damp and unpredictable climate and topography. Crafted from solid wood, such as willow or poplar, clogs offered outstanding protection. Their firm structure kept

Although sending you an SMS (Short Message Service) verification code provides some security, many apps now use code-generating apps and two-factor authentication instead. But more recently, passkeys now use a biometric approach to logging in. Biometrics can offer an even more secure alternative. Following this trend, Google is reportedly planning to replace SMS verification codes with “QR code” scanning. SMS codes are currently used to verify user identity and prevent fraudsters from creating fake Gmail accounts to distribute spam. However, these codes present several challenges. They can be phished through suspicious links, and users may not always have access