Andrew Broughton still remembers the first celebrity autograph he ever got.

“It started by accident,” he says, when he was 13 and doing a project about horror films at school. “I love Hammer horror. I wrote a letter to [actor] Peter Cushing and sent it to the BBC. A large envelope came back and a lovely letter. He sent me some signed film stills. So I got the bug. I just thought: there’s nothing to stop me writing to anybody.”

Since then, Broughton, 62, has collected autographs from some of the biggest stars in TV, film, music and sports, as well as royalty, politicians and world leaders. The walls of his home in Derby are covered in framed signed photos from the late queen, King Charles, Diana, Princess of Wales, Brigitte Bardot, John Travolta, Kylie Minogue, Elton John, Liza Minnelli, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers and Muhammad Ali. Broughton supplements the signatures he requests with ones he has bought at auctions and private sales. He estimates he has 10,000 in his collection.

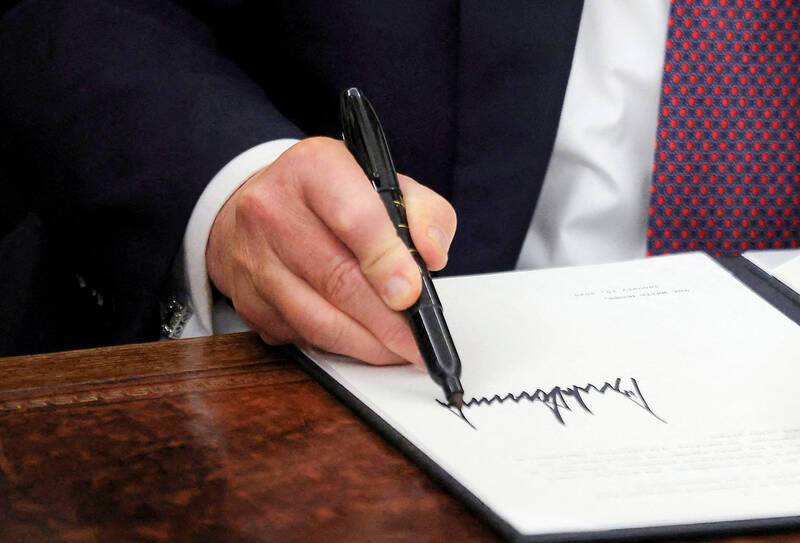

Photo: Reuters

“I’ve got all the prime ministers of my lifetime through to Keir Starmer now; I’ve got a contact in Downing Street. When the prime minister changes, I send a photograph in. They know who I am.”

He hangs these photos on the wall along his stairs. He’s also got autographs from all the American presidents since Richard Nixon.

“Donald Trump was really hard to get. I wrote to him saying how big the collection was and they made an exception,” he says.

Broughton’s hobby even led to an invitation to the wedding of the then Prince Charles and Camilla Parker Bowles in 2005. He first wrote to Parker Bowles in the 90s at the height of public animosity towards her.

“I said: ‘I just want you to know that not everybody hates you.’”

She sent a letter back.

“She said: ‘Thank you so much. It really has restored my faith in humanity.’”

They started corresponding regularly. He took his sister along to the wedding, where he was invited to stand outside Windsor Castle.

“She came straight over to us. I said my name. We shook hands. She said: ‘It’s lovely to put a face to the name. Don’t stop writing.’

Then the king came. He said he’d heard so much about me. She’d obviously been talking about me. It was quite a surreal day.”

ACTIVE APPROACH

While Broughton has managed to indulge in his passion from the comfort of his own home, Jason Thanos has taken a more active approach to collecting autographs. The 51-year-old, who lives in Manchester, runs Movie Art Gallery, an online shop which sells autographed and limited edition film posters. He started autograph hunting for fun when he was in his 20s after spotting Matthew Perry and Minnie Driver leaving the Comedy theater in London. He only started selling autographed memorabilia after being inundated with requests from his friends to get autographs for them.

He travels to film festivals around the world, attends premieres and waits outside luxury hotels to meet some of the biggest stars in Hollywood and get their signature. He’s got autographs from Angelina Jolie, Russell Crowe, Tom Cruise, Pamela Anderson, Tom Hanks and Robert De Niro. His favorite autograph came from Roger Moore, who he met several times.

“Every time I’d get Roger Moore, I’d say: ‘Oh man, you’re my favorite Bond.’ He’d say: ‘Sean Connery told me that’s what you say to him.’”

It once took him five days to get Sylvester Stallone’s autograph. He flew to the Rome film festival where the action star was premiering his latest film, Bullet to the Head.

“I managed to get him on the final night. I was very courteous. Because I wasn’t being an idiot, he gave me a beautiful signature, and wrote the message: ‘keep punching’ [a reference to Stallone’s time as boxer Rocky Balboa].”

LUCRATIVE BUSINESS

Selling autographs can be a lucrative business, especially if they are signed on memorabilia. The most expensive ever sold is thought to be George Washington’s personal annotated copy of the US constitution and Bill of Rights, which was auctioned in 2012 for US$9.8 million (£7.3 million). A rookie trading card signed by the basketball star Stephen Curry sold for US$5.9 million (£4.4 million) in 2021, while a white Fender Stratocaster, signed by 19 rock legends including Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Eric Clapton, was auctioned for US$2.7 million (£2 million) in 2005 to raise money for survivors of the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami. The Double Fantasy album that John Lennon signed for his killer, Mark Chapman, was sold for US$900,000 (£673,000) in 2020.

Thanos sells his signed posters for between £75 and £4,000. He once got £5,000 for a signed jacket from Arnold Schwarzenegger. But, he says, he usually spends more money than he gets back from autograph hunting: taking in travel and accommodation, he estimates it costs him about £4,000 to attend a film festival such as Cannes or Toronto. But it isn’t just about getting autographs.

“I get to watch movies that won’t be out for six months. I’m a proper fan. I can tell you about every movie, every genre, every actor, because it’s my passion. I love movies a lot.”

The first signature from a major historical figure is believed to be by the Spanish knight El Cid in 1098, who signed documents in his Latin name. Autograph hunting as a hobby and a business took off in the 19th century, with collectors snapping up signatures of notable figures such as writers Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper. Demand grew in the 20th century as cinema, radio and television became more popular and, these days, celebrities attending conventions such as San Diego Comic-Con can charge fans for autographs and photos.

For Clare Hodges, 56, a retail assistant from Frampton on Severn, Gloucestershire, autograph hunting has long been a fun family pastime.

“My dad had a collection, and I just enjoyed looking at his. I thought: ‘I’m going to try.’” She joined the Bucks Fizz fanclub when she was 13, which sent out an autographed photo. “Me and my brother used to collect them together. He stopped after a few years, but I continued with the hobby.” She sends out about 30 letters a month requesting autographs and also likes to visit theaters to wait outside the stage door.

“It’s a bit of an addiction,” says Hodges, who has autographs from celebrities including Joan Collins, Kate Bush and Stephanie Beacham. “I love to meet famous people. I get the photographs [for them to sign] beforehand, and take them with me with my Sharpies. I try to get a selfie with the people I meet as well.”

Ringo Starr, Paul McCartney and William Shatner are some of the celebrities who have said in past interviews that they don’t sign autographs. Steve Martin used to carry business cards which he gave to fans who asked him for an autograph, which certified they’d had “a personal encounter” with the film star, although he has been spotted since then signing them. In 2018, Bryan Cranston announced on X, formerly Twitter, that he was “overwhelmed by requests and I just can’t do it any more.”

Many celebrities who decline to give out autographs cite worries over them being sold on. In 2023, Bill Hader said on the Happy Sad Confused podcast that he was no longer signing autographs.

“I used to sign stuff, and then one time I saw somebody and they had their kid come up to me to sign a [Star Wars] BB-8 thing, and it was three in the morning … [They] were like: ‘Go over there so he’ll sign it so I can sell it online.’ I was like: ‘That’s fucked up.’”

Earlier this year, footage of Manchester City manager Pep Guardiola went viral after he became frustrated with young fans who asked him to sign boxes of memorabilia. He told them: “Don’t come again, I will not sign again, I know your faces. Go to school and prepare yourselves, you are young, don’t be here wasting your time. Do you want to live your life doing this?”

Broughton says autograph hunters who go on to sell their celebrity signatures are “ruining it for true collectors.” But Thanos, who estimates his personal collection used to be about 30,000 signatures before he sold some of them, says he has his priorities straight.

“For me, the most important thing in my life is my daughter. If I have to sell autographs to make sure my daughter has the best of the best, that’s what I’ll do.”

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how

“‘Medicine and civilization’ were two of the main themes that the Japanese colonial government repeatedly used to persuade Taiwanese to accept colonization,” wrote academic Liu Shi-yung (劉士永) in a chapter on public health under the Japanese. The new government led by Goto Shimpei viewed Taiwan and the Taiwanese as unsanitary, sources of infection and disease, in need of a civilized hand. Taiwan’s location in the tropics was emphasized, making it an exotic site distant from Japan, requiring the introduction of modern ideas of governance and disease control. The Japanese made great progress in battling disease. Malaria was reduced. Dengue was