The elite Central Committee of China’s ruling Communist Party will hold a closed-door meeting from Monday to Thursday to discuss, among other things, the country’s 15th five-year development plan.

The meeting, known as a plenum, is the fourth since the 2022 Party Congress. Here is what it all means:

WHAT’S A PLENUM?

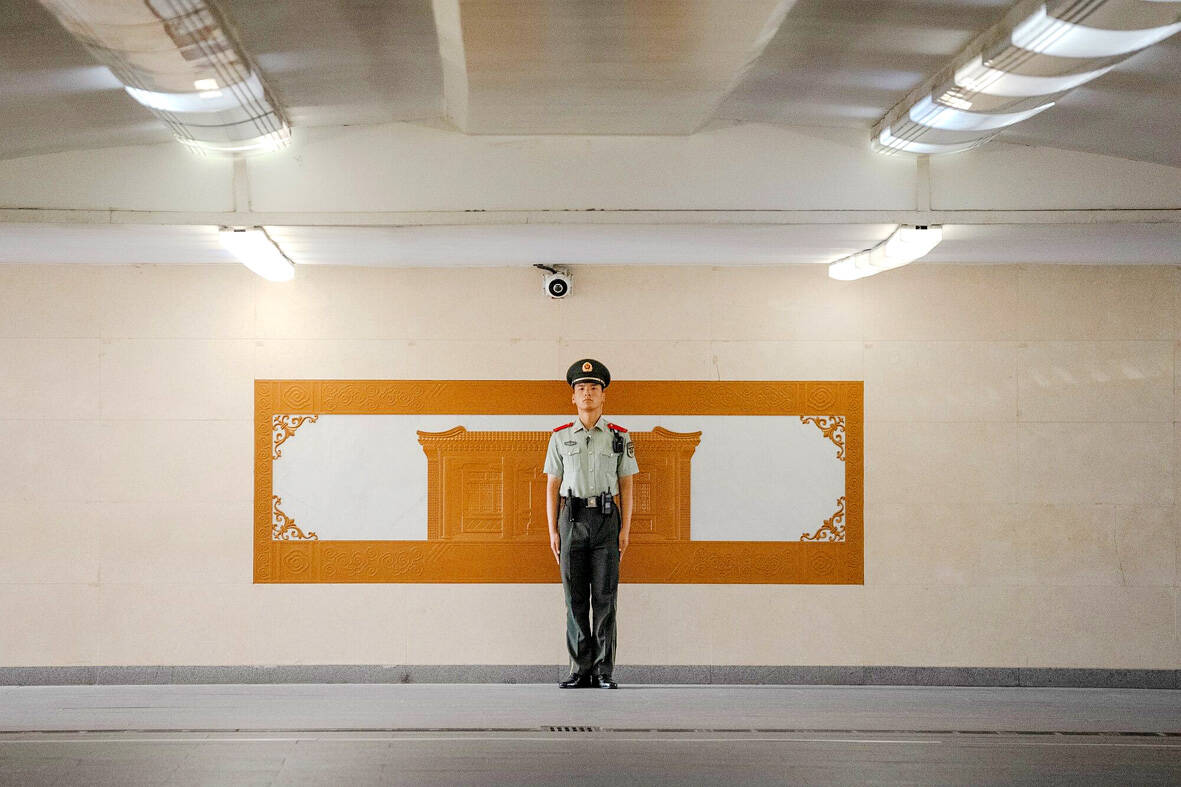

Photo: Bloomberg

The Central Committee is the largest of the party’s top decision-making bodies, and it typically holds seven plenums between congresses, with the fifth traditionally deliberating on five-year plans.

But due to an unexplained nine-month-long delay in the third plenum until July last year, the party is expected to now review the 2026-2030 plan during the fourth, on Oct. 20-23.

To prevent leaks, plenum attendees are traditionally confined to the venue for the duration of the meeting. Little, if any, news of the proceedings is made public until it closes. Foreign media and most Chinese reporters don’t have access.

On the day the plenum ends, China releases a brief report outlining what was agreed — this time, the general scope of the next five-year development plan. To project party unity, there will be no mention of any dissent.

Some days later, potentially on the week starting Oct. 27, Beijing releases more details, although it’s unlikely these would contain specific targets or costs for any new policies.

These are more likely to be released in March, when parliament approves the next five-year plan.

WHAT’S A FIVE-YEAR PLAN?

It’s a strategic blueprint that outlines economic and social development goals over a five-year period, guiding national policy, investment and reform.

It typically covers economic growth, industrial modernization, technological innovation, environmental protection, national security and social goals.

The 2026-2030 plan will be China’s 15th five-year plan since it adopted Soviet-style quinquennial policy formulation cycles in the 1950s.

The 1980s plans were seen as pivotal in China’s staggering subsequent development into the world’s second-largest economy. These reforms allowed private ownership, opened up its markets and paved the way for the country’s integration into global trade.

The 2000s and 2010s focused on poverty alleviation and transitioning towards an economic model relying more on domestic consumption than on infrastructure investment and manufacturing.

China has declared success in fighting poverty. But it is widely accepted that it fell short on fostering durable household demand.

WILL THE PLENUM DISCUSS OTHER TOPICS?

Most likely.

Fourth plenums have in the past deliberated on party governance, including personnel reshuffling and disciplinary actions.

Diplomats and other observers will look at the people who might fall from grace or rise through the ranks, particularly in the military, to better understand Beijing’s thinking.

WHAT’S AT STAKE

The next five-year plan will be closely watched for how much emphasis China places on rebalancing its economy.

Most observers expect strong language from Beijing on its intentions to boost consumption.

In practice, however, analysts say the trade war with the US is likely to keep policymakers focused on industrial upgrading and technological breakthroughs, which means resources would by and large keep flowing towards factories and strategic investments rather than consumers.

This might consolidate China’s achievements in developing world-leading industries, such as electric vehicles or green energy and open up opportunities in other sectors where it still lags rivals, such as semiconductors or aircraft.

But it also means deflationary forces will persist and debt will accumulate, while China’s limited contribution to global demand relative to its growing stake in the supply of manufactured goods will keep tensions high.

The plenum comes days before an APEC summit in South Korea, where Presidents Xi Jinping (習近平) and US President Donald Trump might meet. It also comes days after Beijing tightened export controls on rare earths, prompting a threat from Trump of triple-digit tariffs.

Five-year plans don’t change on short-term fluctuations in diplomatic and trade relationships, but analysts say Beijing sees protecting national interests in times of growing great power rivalry as the basis of every policy it formulates.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not