July 14 to July 20

When Lin Tzu-tzeng (林資曾) arrived in Sansia (三峽) in 1830, he found the local conditions ideal for indigo dyeing. Settlers had already planted indigo across the nearby hills, the area’s water was clean and low in minerals and the river offered direct transport to the bustling port of Bangka (艋舺, modern-day Wanhua District in Taipei).

Lin hailed from Anxi (安溪) in Fujian Province, which was known for its dyeing traditions. He was well-versed in the craft, and became wealthy after opening the first dyeing workshop in town. Today, the sign for the Lin Mao Hsing (林茂興) Dye House can still be seen on picturesque Sanxia Old Street. Near the top of the facade is a row of Chinese characters, which state: “Lin Mao Hsing Co independently handles dyeing and selling bolts of cloth to overseas provinces.”

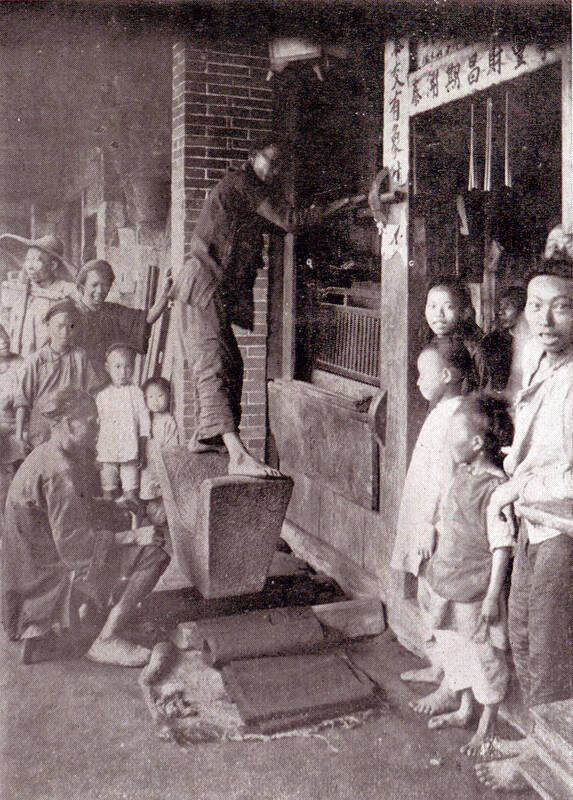

Photo courtesy of the Archives of Institute of Taiwan History

Sanxia already had a significant Anxi majority, and over time more dye masters arrived and set up shop, eventually totalling more than 20 at the industry’s peak. They processed imported textiles coming down the river from Bangka and sent the dyed fabrics back for export. Utilizing local plants and conditions, these artisans developed a distinctive indigo style that was prized in China and later by the Japanese colonial authorities.

The traditional dyeing industry thrived until around 1920, when it began a precipitous decline due to economic and technological changes. It eventually collapsed in the 1940s.

Fifty years later, however, local artisans began reviving the craft. Today the town celebrates its heritage through the annual Sansia Indigo Dye Festival (三峽藍染節), which runs until Aug. 10 with installations, exhibitions, craft markets, workshops and other events.

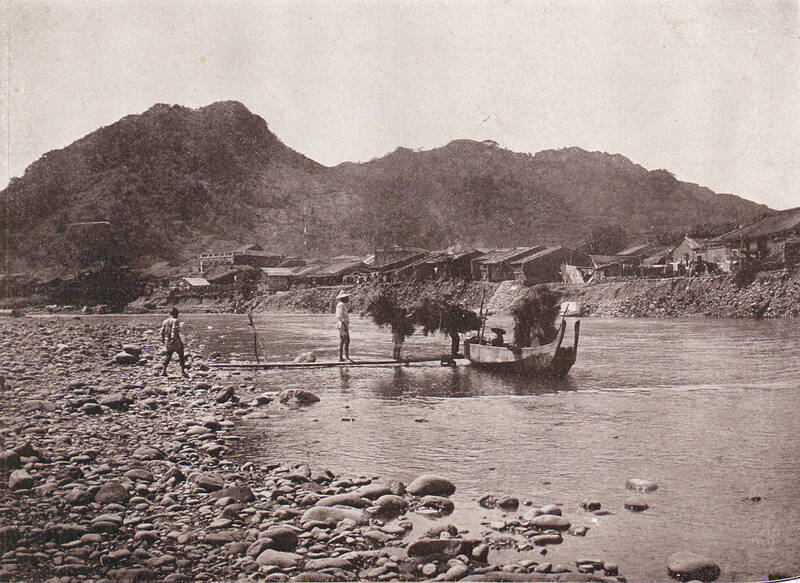

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

For details (Chinese only), visit: www.facebook.com/Sanxia.Indigo.Dyeing.Festival.

DYE CENTER

In “The color of natural dye — The rise and fall of Taiwan’s indigo industry” (天染之色—臺灣藍靛業的興衰), Tsai Cheng-hao (蔡承豪) writes that the Dutch introduced Indigofera tinctoria (true indigo) plants from China and Southeast Asia during their rule in the 1600s. Some products were even exported to Europe, but due to high costs and Taiwan’s unpredictable weather, the industry never took off.

Photo courtesy of New Taipei Hakka Affairs Department

Nevertheless, true indigo was a hardy plant that was easy to grow, and Han settlers cultivated it across Taiwan’s western plains, exporting dyed goods to China. Indeed, Qing Dynasty annals often praised Taiwan’s superior indigo quality.

However, this was not the type of indigo that put Sansia on the map. That was Strobilanthes cusia (Assam Indigo), which flourished in humid, shaded hills. During the 1700s, the population of Han settlers grew in the Taipei Basin, farming and raising livestock on flatter land and growing sweet potato and Assam indigo on the surrounding hills, writes Lin Chiung-jen (林炯任) in “The development and changes of Sansia’s indigo dyeing industry” (三峽藍染業的發展與蛻變).

These farmers built stone pools to extract the dye, some of which can still be seen today. Carrying the product on shoulder poles, they traveled down “indigo roads” to the riverside towns, where the dye was shipped to merchants in Bangka and other towns along the Tamsui River. From there it was sent to local dye houses or exported to China and Japan.

Photo: Lin Yi-chang, Taipei Times

Bangka emerged as the most important hub for Taiwan’s indigo trade because its merchants were early investors in the plantations. At the height of the trade in the 1870s and 1880s, buckets of indigo lined the Tamsui River, waiting to be shipped off to ports along the Chinese coast. Civil unrest in China had disrupted indigo production, leading to the need for dye and colored textiles from Taiwan.

SANSIA’S RISE

Han settlers arrived in Sansia in the early 1700s, initially renting land from the Indigenous Pingpu peoples before eventually displacing them. The riverside town of Sanjiaoyong (三角湧), where today’s old street is located, emerged around 1780. Located at the confluence of the Dahan (大漢), Sansia (三峽) and Heng (橫) rivers, it had easy access to Bangka.

Photo: Chang An-chiao, Taipei Times

After a series of armed conflicts between settlers from different regions of southern China, the Anxi settlers emerged as the dominant group. While they cultivated Assam indigo, the first recorded instance of large scale production was in 1822, when Bangka merchant Weng Tian (翁添), invested in the area and also introduced true indigo. As the settlers pushed further into the mountains, they ran into resistance from the Indigenous Atayal, who often raided the farms and settlements.

To secure his enterprise, Weng dispatched border guards, and hired workers from China to extract the indigo. He exported the dye to China, and imported cloth and other goods. This spurred the development of river shipping between Bangka and Sansia. During the town’s heyday in the late 1800s, more than 80 ships traversed these waters, transporting not just indigo but local tea, camphor, timber, furniture, coal and rice noodles.

By 1830, conditions were ripe for Lin Tzu-tzeng to set up the area’s first dye house. Others followed, and eventually the old street was lined with them. Artisans did the dyeing in buckets in the back of the shops, then rinsed the cloth in the Sansia River and pressed it flat with a large stone roller.

Photo: CNA

These dyemasters adjusted their methods according to local conditions, incorporating local flora, creating a unique “sanjiaoyong” dye that was highly prized both in China and by the Japanese colonizers.

END OF AN ERA

Although many farmers converted their indigo fields into far more lucrative tea plantations after the rise of Taiwanese tea in the 1870s, Sansia’s dye houses continued to prosper, entering a golden age that lasted until 1920. At one point, indigo production fell so low that Taiwan had to import dye from China. However, after the Japanese subjugated the Atayal in the area in 1906, they encouraged farmers to cultivate more indigo in the mountains.

The invention of synthetic indigo by German chemist Adolf von Baeyer in 1897 marked the beginning of the end for traditional dyeing. The compound reached Taiwan in 1913, and Sansia dye houses began experimenting with blends of synthetic and natural dye, cutting both time and costs.

Lin Chiung-jen writes that the ultimate reason for the industry’s demise was changing fashion preferences toward Western and Japanese clothing, as well as the rise of mechanized dye factories. By the 1930s, only a handful of dye houses remained in Sansia, and by the 1940s the craft had ceased to exist.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the

As devices from toys to cars get smarter, gadget makers are grappling with a shortage of memory needed for them to work. Dwindling supplies and soaring costs of Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) that provides space for computers, smartphones and game consoles to run applications or multitask was a hot topic behind the scenes at the annual gadget extravaganza in Las Vegas. Once cheap and plentiful, DRAM — along with memory chips to simply store data — are in short supply because of the demand spikes from AI in everything from data centers to wearable devices. Samsung Electronics last week put out word