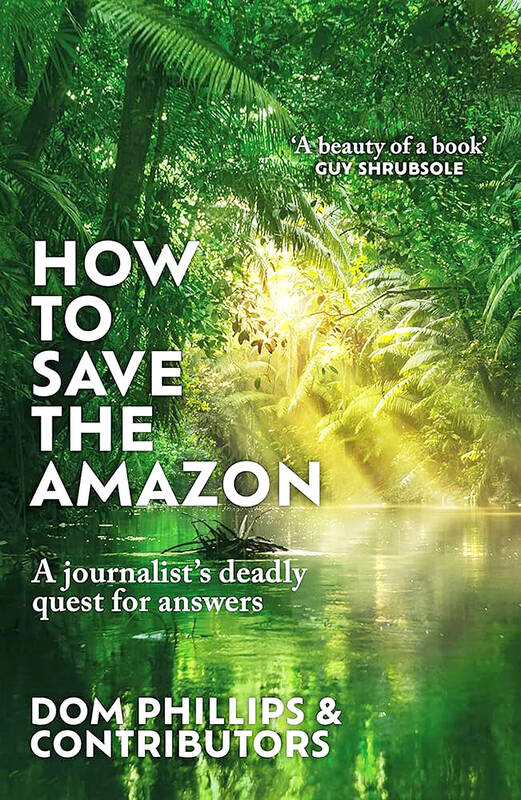

On page 165 of How to Save the Amazon, a black-and-white photo interrupts the text. Two wooden crucifixes stand in a freshly hacked clearing, lashed to tall, thin stumps. One of them bears the name Bruno Pereira. The other, Dominic Phillips, the author. The image splits the book in two. Before it, the pages are filled with Phillips’s vivid prose. After it, his friends and former colleagues have gathered and attempted to complete his work as best they can.

Erected on the bank of the Itaquai river, in a remote part of the Brazilian Amazon, the crosses mark the spot at which – early on the morning of 5 June 2022 — Pereira and Phillips were murdered. The two men had been traveling downriver in a small motorboat when they were attacked. Pereira, a Brazilian forest protector and Indigenous specialist, was shot first: three times, including in the back. Phillips, a Guardian reporter, was shot once in the chest, at close range. His final word, according to his alleged killers, was “No.”

Except that wasn’t to be his final word, not by far. He left a half-finished manuscript and much of the raw material that, filtered and processed by his particular mind, would have made up the rest. He had a plan, and many ring binders full of handwritten notes from river expeditions, road trips, hundreds of interviews and reams of research.

Empowered by Alessandra Sampaio, Phillips’s widow, a committee made up of journalists Andrew Fishman, Tom Hennigan, Jonathan Watts and David Davies, as well as Phillips’s agent, Rebecca Carter, assumed the responsibility of making it all mean something.

“Nothing good could come from such a heinous murder,” they write in their foreword, “but we could at least prevent the killers from silencing the story that Dom had been trying to tell.”

A two-year investigation into the murders concluded last year with federal charges against an alleged illegal fishing and poaching mastermind, who denies any involvement.

Phillips’s half of How to Save the Amazon begins in the same place the author’s life ended: on an expedition to the Javari valley with Pereira. Death is there, lurking in the undergrowth, from the start. Phillips muses freely on all the ways he might die. There are the jararaca snakes his Indigenous companions swat like flies, the giant hornets, caiman, anacondas and jaguars, not to mention the risks posed by illegal gold miners and loggers, armed fishing gangs, and narco traffickers.

The unintended pathos this creates is soon overcome. The Javari valley — a protected territory home to the world’s highest concentration of voluntarily isolated Indigenous groups — is where Phillips’s passion for the Amazon is born, and that passion leaps from the page. From his first taste of roast monkey — “its deliciously charred, fatty meat, like pancetta” — it’s clear that Phillips’s voice is one worth listening to: he is open to experience, unafraid to take risks, flexible in his thinking.

That the Amazon is in need of passionate attention is beyond doubt. Twenty percent of the Brazilian Amazon has been deforested — most of that within the last few decades — bringing it dangerously close to what climate scientists have identified as a “tipping point,” after which the entire thing is likely to die back to semi-arid savannah, with catastrophic consequences for South America and the world.

The complex web of crime and bad law that makes this possible is its own evil ecosystem, an anti-rainforest liquidating the Amazon’s natural riches and converting them into what the Kayapo call “sad leaves” — money. The main scam, as Phillips describes it, works something like this: you select a swathe of the Amazon and illegally log it. Then you set fire to whatever is left, and send in the cows. The cows are important because, under Brazilian property law, productivity and ownership go hand in hand, and cows — by dint of their expansive pasture requirements — are the simplest way to lay claim to vast tracts of land.

Could better laws save the Amazon? Even the useful ones — such as the requirement for Amazonian farmers to leave 80 percent of their land forested — are frequently ignored, and illegal gold miners and loggers often operate in plain sight.

“It’s difficult,” Phillips writes, “to think of anywhere else outside of a war zone where it’s so easy to find people blatantly breaking the law.”

He is cautiously optimistic about the possibility of using agroforestry — an agricultural system that emulates the forest — to recover cleared land, but the thought is underdeveloped. The fact is, Phillips was just hitting his stride when he and Pereira were felled by the destructive forces he’d taken such care to describe.

“No reader should be in any doubt that these pages have been stained by blood,” write his successors. “The killers blasted a gaping wound in this book that is far too great for any infusion of solidarity to heal.”

Over the final half-dozen chapters, Phillips’s fellow writers — Jon Lee Anderson, Eliane Brum, Stuart Grudgings, Beto Marubo, Helena Palmquist and Tom Phillips, as well as those previously mentioned — struggle with Phillips’s impossible handwriting, retrace his footsteps and reveal tantalizing flashes of what could have been. The result is a book both brilliant and broken, one that is ultimately as inspiring and devastating as the Amazon itself.

Last week gave us the droll little comedy of People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) consul general in Osaka posting a threat on X in response to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi saying to the Diet that a Chinese attack on Taiwan may be an “existential threat” to Japan. That would allow Japanese Self Defence Forces to respond militarily. The PRC representative then said that if a “filthy neck sticks itself in uninvited, we will cut it off without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared for that?” This was widely, and probably deliberately, construed as a threat to behead Takaichi, though it

Nov. 17 to Nov. 23 When Kanori Ino surveyed Taipei’s Indigenous settlements in 1896, he found a culture that was fading. Although there was still a “clear line of distinction” between the Ketagalan people and the neighboring Han settlers that had been arriving over the previous 200 years, the former had largely adopted the customs and language of the latter. “Fortunately, some elders still remember their past customs and language. But if we do not hurry and record them now, future researchers will have nothing left but to weep amid the ruins of Indigenous settlements,” he wrote in the Journal of

Even after years in business, weekend tables here can be booked out a month in advance. The price point far exceeds its competitors. Granted, expectations are soaringly high, but something here failed to hit the high notes. There are a few telltale signs that a restaurant relies solely on outstanding food to create the experience, no gimmicks or distractions needed. La Mole is such a restaurant. The atmosphere is food-forward, with an open kitchen center stage. Our tables are simple; no candles, no dim lighting, no ambient music. The menu is brief, and our waiter directs most

If China attacks, will Taiwanese be willing to fight? Analysts of certain types obsess over questions like this, especially military analysts and those with an ax to grind as to whether Taiwan is worth defending, or should be cut loose to appease Beijing. Fellow columnist Michael Turton in “Notes from Central Taiwan: Willing to fight for the homeland” (Nov. 6, page 12) provides a superb analysis of this topic, how it is used and manipulated to political ends and what the underlying data shows. The problem is that most analysis is centered around polling data, which as Turton observes, “many of these